You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

PLAN Aircraft Carrier programme...(Closed)

- Thread starter bd popeye

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

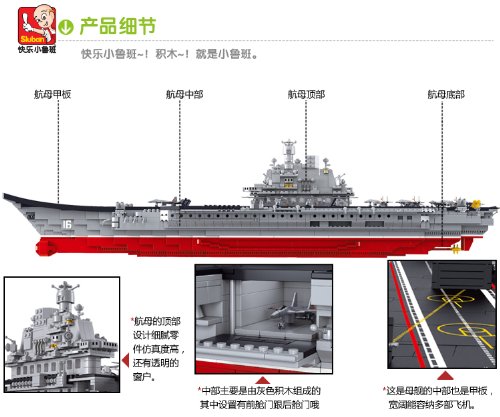

Yes. You can buy them here on ! They are a leggo-like carrier with...get this...over 1800 pieces. Other pics:

Skywatcher

Captain

I don't suppose it comes with any of the flight/deck crew?

Actually, there is a model accessory company called E'Duard from France who does sell 1/350 scale personnel specifically for aircraft carriers. Already painted. Very reasonably priced.I don't suppose it comes with any of the flight/deck crew?

Here's some on my 1/350 scale Enterprise, CVN-65, by Tamiya (this is not a leggo model). You can see them on the bridge here, in the island.

Last edited:

Skywatcher

Captain

Awesome! *goes off to mark wishlist*

Multiply that six months by ten and you will get five years, and that would be a more realistic target. Meanwhile, PLAN is now another step ahead by utilizing the starboard launch position.

Tags: China; Liaoning; J-15 take off; aircraft carrier; starboard launch position;

They are still training deck crew. There are three yellow shirts on the fore deck where usually should be just one.

vesicles

Colonel

which is good to see. The training of deck crew is fully expected. Actually, they better be doing more of that.They are still training deck crew. There are three yellow shirts on the fore deck where usually should be just one.

The view from Canada.

Chinese aircraft carrier fails to make a splash with Canadian military officials

Anyone arguing for sending more Canadian naval forces to the Pacific to guard against China’s growing economic and military power might want to avoid mentioning the Asian country’s new aircraft carrier.

The Liaoning, which is named after a province in northeastern China, was unveiled to much fanfare in September 2012 as part of an ongoing Chinese effort to flex its muscles and assert itself as a major player in its neighbourhood and around the globe.

Yet a secret briefing note for then-defence minister Peter MacKay written last December and obtained by Postmedia News indicates Canadian military officials were largely unimpressed.

The Canadian officials acknowledged the aircraft carrier puts China among a handful of countries with the potential ability to launch and recover aircraft at sea.

But the note makes clear they believe it will be years until China will be able to make full use of those capabilities, and even then with many limitations.

The assessment is based largely on Chinese state media reports, and includes photographs and video of Chinese military helicopters and experimental J-15 Flying Shark fighter jets taking off from the aircraft carrier and landing.

Canadian officials quoted the deputy commander of the Chinese navy as having “asserted that pilots have ‘mastered’ take-off and landing skills, even under unfavourable conditions such as poor visibility and unstable airflow.”

“The photographs and videos of the drill, however, show a sunny day with a calm sea state.”

Canadian military officials also cited Chinese media reports that five pilots had taken off and landed on the carrier, “though photographs and video of the event show only two planes landing and one plane taking off."

And they noted that the Liaoning is much smaller and less capable than its American counterparts, while the J-15 fighter jets “used in the drills are themselves test aircraft, with full production many years away.”

The officials quoted Richard Bitzinger, senior fellow of the Military Transformations Programme at Singapore’s Rajaratnam School of International Studies, as questioning the number of aircraft the Liaoning could carry as well as its operational capabilities.

“Deck space and layout will be at a premium, since the J-15 will need to run about half the length of the warship at full afterburner for a ramp-assisted launch,” the report cites Bitzinger as saying. “This would make it challenging, if not impossible, to conduct the simultaneous launch and recovery of aircraft.”

Former Royal Canadian Navy commander Paul Maddison said in an interview that while it’s true the Liaoning may not be an immediate game-changer for the Chinese military, its presence in the Asia-Pacific region is significant.

“The introduction of a carrier capability is a significant step by any major navy and it sends a strong signal to the rest of the world to stand up and take notice,” he said. “I don’t think anybody is dismissing this out of hand as kind of an overstated bit of theatre by the (Chinese navy), not at all. And I have no doubt they will field a competent carrier capability sometime in the first half of the century.”

The Liaoning was originally built by the Soviet Union as a hybrid cruiser-aircraft carrier and operated under the name Varyag until it was sold to China by Ukraine. Its unveiling as the Liaoning last year came after a decade of Chinese renovations and repairs.

There has been a debate in some circles in recent months over whether Canada should shift more of its military assets, particularly those of the Royal Canadian Navy, towards the Pacific.

Several other countries have already done so, including the United States, which has stated it will maintain 60 per cent of its military in the region.

This move is widely seen as a response to China’s growing economic and military might, which has been matched by increasing tensions with some of its neighbours over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea and the surrounding region.

University of British Columbia post-doctoral fellow David McDonough, who has argued that the Canadian navy should position more ships on the West Coast, said he wasn’t surprised Canadian military officials would discount the Liaoning.

“China is still in the midst of trying to master carrier aviation, which our American partners have been practising for several decades,” he said in an email.

But while the Liaoning can’t compare with U.S. navy “supercarriers,” McDonough said the Chinese carrier changes the military dynamic in the South China Sea and with China’s immediate neighbours.

It also highlights the Chinese military’s long-term goal of fielding a navy with global reach.

The Canadian navy has 18 of its frigates, supply vessels and other major warships based out of Halifax, versus 15 in Esquimalt, B.C.

Maddison downplayed the difference in numbers between the East and West Coast, saying the Canadian navy moved away from a Euro-centric, Halifax-based position to also focus on the Asia-Pacific region in the 1990s.

“So I don’t see a need to have a huge conversation about rebalancing, refocusing, reprioritizing,” he said. “We’ve been all over this.”

Last edited by a moderator:

peterAustralia

New Member

the article makes some good points

because there is no catapult, the take-off point has to be further aft than otherwise. This could interfere with simultaneous takings and landings. The large take off roll means more deck space is used for take off, this reduces deck space for storing aircraft on deck.

So in my opinion, China should build some small helicopter carriers, flat decked, around 25,000t. For future carriers it looks as though they need to develop catapult technology, alternatively if catapult technology proves too difficult they should go for larger carriers or unconventional layouts like catamarans, where 2 parallel runways can be used, and the full length of the runway can be used for takeoff.

So, Lianong looks like a good ship for learning skills on, beyond that, not quite as much.

because there is no catapult, the take-off point has to be further aft than otherwise. This could interfere with simultaneous takings and landings. The large take off roll means more deck space is used for take off, this reduces deck space for storing aircraft on deck.

So in my opinion, China should build some small helicopter carriers, flat decked, around 25,000t. For future carriers it looks as though they need to develop catapult technology, alternatively if catapult technology proves too difficult they should go for larger carriers or unconventional layouts like catamarans, where 2 parallel runways can be used, and the full length of the runway can be used for takeoff.

So, Lianong looks like a good ship for learning skills on, beyond that, not quite as much.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.