This is clearly US's end goal. China needs to be cautious about sabatoge as well. I wonder if they are keeping quiet on their progress with EUV and DUV machines because they want to keep their cards close to their chest or if they have not gotten any breakthroughs.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Germany Carl Zeiss, heart of Dutch ASML Lithography Equipment.

- Thread starter tidalwave

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Done some research and found out that the US Govt is mainy targeting Huawei Chip design arm Hisilicon and trying to stop its Chip design capability and stopping it from getting TSMC to produce Huawei designs.

Huawei can still apparently partner with Korean companies(Samsung), Qualcomm and even Chinese companies like Unisoc to supply them with the latest off the shelf 7nm Chips or even 5nm chips. This should give Huawei some breathing space while SMIC goes to work in improving its capabilities.

What is critical for advanced Chip manufacturing industry in China is for the SMEE 28nm DUV Immersion Lithography machine which is to be ready in December to be adopted by the leading FABs in the country. This will allow manufacture of 7nm Chips for Huawei and local companies.

This machine will have to be used as Changchun Institutes 125W EUV Lithography machine will only be ready in about 2 years.

Huawei can still apparently partner with Korean companies(Samsung), Qualcomm and even Chinese companies like Unisoc to supply them with the latest off the shelf 7nm Chips or even 5nm chips. This should give Huawei some breathing space while SMIC goes to work in improving its capabilities.

What is critical for advanced Chip manufacturing industry in China is for the SMEE 28nm DUV Immersion Lithography machine which is to be ready in December to be adopted by the leading FABs in the country. This will allow manufacture of 7nm Chips for Huawei and local companies.

This machine will have to be used as Changchun Institutes 125W EUV Lithography machine will only be ready in about 2 years.

This is clearly US's end goal. China needs to be cautious about sabatoge as well. I wonder if they are keeping quiet on their progress with EUV and DUV machines because they want to keep their cards close to their chest or if they have not gotten any breakthroughs.

Interesting link...

If successful, this effort would enable the United States to work with Taiwan and South Korea to constrain China’s use of chips — through end-use and end-user export controls45— to ensure consistency with U.S., allied, and global interests. Importantly, to avoid import substitution by China’s domestic chip fabs, these states should export chips to China for peaceful commercial purposes, with exceptions for the CCP’s military and authoritarian surveillance apparatus.46

The highest priority for more stringent multilateral SME export controls should be photolithography equipment capable of manufacturing ≤45 nm transistors.47These countries already apply ≤45 nm-capable photolithography export controls,48 but typically grant export licenses. This practice should be discontinued. In a commendable start to our suggested approach, the Dutch government recently decided not to renew an export license for ASML to ship EUV photolithography equipment to China.49 Additional priorities include the United States, Japan, and their allies applying more stringent export controls on other types of SME dominated by these countries.50 For these SME supply chain chokepoints, these countries should presumptively deny licenses to export to China.51Foreign-owned fabs capable of manufacturing ≤45 nm in China should also be subject to export scrutiny.52To promote cooperation on export controls and to compensate for the downsides — such as near-term revenue shortfalls — the United States and its allies could partner on semiconductor R&D to maintain their technological advantages

As shown in Figure 7, SME export controls could reduce China’s chip fab capacity share from 15.2% to 10.6%. The effect on China’s quality-adjusted chip fab capacity share would be more dramatic: a fall from 3 to 0.2% — effectively ending China’s hope of competing in advanced chip production for the foreseeable future. Under the proposed export controls, China’s current stock of already-imported ≤45 nm-capable SME would gradually reach end of life,53 and China’s chip fabs capable of manufacturing chips with ≤45 nm transistors would face the prospect of shutting down.5

Chinese losses in fab capacity would be U.S., Taiwanese, and South Korean gains. Because global chip demand is independent of where chips are produced, export controls on SME would, in the long-term, shift China’s lost chip fab capacity to the democracies at the state-of-the-art. Although SME companies may lose out on lucrative Chinese subsidies in the near-term,56 they would experience little revenue harm in the long-term. They would instead benefit from more reliable partners and from a weakened Chinese SME industry.57 In response to the Dutch denial of an export license for ASML’s EUV photolithography equipment exports to China, ASML’s CEO Peter Wennink said, “if we cannot ship to customer A or country B, we’ll ship it to customer C and country D” to meet growing global chip demand, including from China.58 In addition to the advantages of trading with more reliable partners, these SME firms can help undercut the effectiveness of the CCP’s market-distorting subsidies and give democracies greater leverage against the CCP’s military modernization and human rights violations.If SME export controls successfully reduce China’s chip fab capacity, the United States, Taiwan, and South Korea — the only remaining economies with significant near-state-of-the-art chip fab capacity59 — could coordinate on further, targeted end-use and end-user controls to advance the cause of human rights and global stability.

Done some research and found out that the US Govt is mainy targeting Huawei Chip design arm Hisilicon and trying to stop its Chip design capability and stopping it from getting TSMC to produce Huawei designs.

Huawei can still apparently partner with Korean companies(Samsung), Qualcomm and even Chinese companies like Unisoc to supply them with the latest off the shelf 7nm Chips or even 5nm chips. This should give Huawei some breathing space while SMIC goes to work in improving its capabilities.

What is critical for advanced Chip manufacturing industry in China is for the SMEE 28nm DUV Immersion Lithography machine which is to be ready in December to be adopted by the leading FABs in the country. This will allow manufacture of 7nm Chips for Huawei and local companies.

This machine will have to be used as Changchun Institutes 125W EUV Lithography machine will only be ready in about 2 years.

Do you have any links? This seems unlikely, the goal is to prevent not only Huawei from catching up to the advanced chip fabs but all of China (see my post above)

If the only goal for US is to hit the HiSilicon but otherwise leave the rest of Huawei phone division alone, then why need to do the Google ban? Everything is consistent with the US intent to completely kill off Huawei.

China's EUV machine is the only thing in this whole business worth talking about, everything else is a distraction. First, this is a first-generation machine built around an inferior light source - how small is it able to go? From my dive into this topic I got the impression that 300W is necessary for a commercially viable EUV machine. What's the state of research on other EUV approaches (specifically LPP)?This machine will have to be used as Changchun Institutes 125W EUV Lithography machine will only be ready in about 2 years.

This translation is mangled to the point being useless. First, it's unclear when this was written (there's a passage from which we can infer 2020). Second, the technical terms are unclear - there's the passage "2017 In The 13.5nm extreme ultraviolet EUV lithography exposure system with 32nm line width passed the acceptance." What's the characteristic parameter of this machine? To make a long story short, what's the smallest chip size it can make?There have been some online posts about SMEE capabilities. Below I have posted the translated text and links to actual site. I would be curious what people think of this information.

View attachment 59650

But the most offensive phrase by far is "[...] accepted the principle and technology prototype in 2016, and the first verification machine will be rolled out in the past two years." There's a time paradox in that sentence. Does it mean the first verification machine was rolled out in the past two years or will be rolled out in the next two years? Most importantly, how fast can this step and the ones that lie between it and commercialization be accelerated?

That analysis is as useless as it is spiteful. It holds only if China's research and production capability in EUV and DUV lithography is set to zero permanently. As we've seen posted several times, indigenous DUV is essentially a solved problem and can take China down to ~7nm. It's EUV that's the important bottleneck and what our discussion must focus on.Interesting link...

If successful, this effort would enable the United States to work with Taiwan and South Korea to constrain China’s use of chips — through end-use and end-user export controls45— to ensure consistency with U.S., allied, and global interests. Importantly, to avoid import substitution by China’s domestic chip fabs, these states should export chips to China for peaceful commercial purposes, with exceptions for the CCP’s military and authoritarian surveillance apparatus.46

The highest priority for more stringent multilateral SME export controls should be photolithography equipment capable of manufacturing ≤45 nm transistors.47These countries already apply ≤45 nm-capable photolithography export controls,48 but typically grant export licenses. This practice should be discontinued. In a commendable start to our suggested approach, the Dutch government recently decided not to renew an export license for ASML to ship EUV photolithography equipment to China.49 Additional priorities include the United States, Japan, and their allies applying more stringent export controls on other types of SME dominated by these countries.50 For these SME supply chain chokepoints, these countries should presumptively deny licenses to export to China.51Foreign-owned fabs capable of manufacturing ≤45 nm in China should also be subject to export scrutiny.52To promote cooperation on export controls and to compensate for the downsides — such as near-term revenue shortfalls — the United States and its allies could partner on semiconductor R&D to maintain their technological advantages

As shown in Figure 7, SME export controls could reduce China’s chip fab capacity share from 15.2% to 10.6%. The effect on China’s quality-adjusted chip fab capacity share would be more dramatic: a fall from 3 to 0.2% — effectively ending China’s hope of competing in advanced chip production for the foreseeable future. Under the proposed export controls, China’s current stock of already-imported ≤45 nm-capable SME would gradually reach end of life,53 and China’s chip fabs capable of manufacturing chips with ≤45 nm transistors would face the prospect of shutting down.5

Chinese losses in fab capacity would be U.S., Taiwanese, and South Korean gains. Because global chip demand is independent of where chips are produced, export controls on SME would, in the long-term, shift China’s lost chip fab capacity to the democracies at the state-of-the-art. Although SME companies may lose out on lucrative Chinese subsidies in the near-term,56 they would experience little revenue harm in the long-term. They would instead benefit from more reliable partners and from a weakened Chinese SME industry.57 In response to the Dutch denial of an export license for ASML’s EUV photolithography equipment exports to China, ASML’s CEO Peter Wennink said, “if we cannot ship to customer A or country B, we’ll ship it to customer C and country D” to meet growing global chip demand, including from China.58 In addition to the advantages of trading with more reliable partners, these SME firms can help undercut the effectiveness of the CCP’s market-distorting subsidies and give democracies greater leverage against the CCP’s military modernization and human rights violations.If SME export controls successfully reduce China’s chip fab capacity, the United States, Taiwan, and South Korea — the only remaining economies with significant near-state-of-the-art chip fab capacity59 — could coordinate on further, targeted end-use and end-user controls to advance the cause of human rights and global stability.

This translation is mangled to the point being useless. First, it's unclear when this was written (there's a passage from which we can infer 2020). Second, the technical terms are unclear - there's the passage "2017 In The 13.5nm extreme ultraviolet EUV lithography exposure system with 32nm line width passed the acceptance." What's the characteristic parameter of this machine? To make a long story short, what's the smallest chip size it can make?

But the most offensive phrase by far is "[...] accepted the principle and technology prototype in 2016, and the first verification machine will be rolled out in the past two years." There's a time paradox in that sentence. Does it mean the first verification machine was rolled out in the past two years or will be rolled out in the next two years? Most importantly, how fast can this step and the ones that lie between it and commercialization be accelerated?

The 0.75nm RMS is important in regards to development of the optical surfaces.

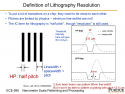

13.5nm is due to the materials being used (tin droplet), the "linewidth":

Line width is effectively resolution I think.

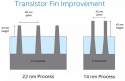

If you look at how people define their gates, the 14nm and whatever don't mean much. You need full details how the node.

From wikichip:

Historically, the process node name referred to a number of different features of a transistor including the as well as M1 half-pitch. Most recently, due to various marketing and discrepancies among foundries, the number itself has lost the exact meaning it once held. Recent technology nodes such as , , , and refer purely to a specific generation of chips made in a particular technology. It does not correspond to any gate length or half pitch. Nevertheless, the name convention has stuck and it's what the leading foundries call their nodes.

Since around 2017 node names have been entirely overtaken by marketing with some leading-edge foundries using node names ambiguously to represent slightly modified processes. Additionally, the size, density, and performance of the transistors among foundries no longer matches between foundries. For example, Intel's is comparable to foundries while Intel's is comparable to foundries .

Where's the original text?

@Pkp88

Last edited:

The 0.75nm RMS is important in regards to development of the optical surfaces.

13.5nm is due to the materials being used (tin droplet), the "linewidth", lemme go read up and come back with summary.

Where's the original text?

@Pkp88

The original post has the direct un-translated links (via google not the best i know). I would like to direct attention to the below article I found (Jan 2020) from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in relation to work on Lithography.

Just found some really interesting news on the Shanghai Academy of Sciences site (Translated text below)

- Status

- Not open for further replies.