That's based on 24 fighter wing?Interesting thread on J15 sortie rates. Seems CV16 can do 37 per day and CV17 47 per day sustained for about a week.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

CV-16, CV-17 STOBAR carrier thread (001/Liaoning, 002/Shandong)

- Thread starter Blitzo

- Start date

That 110 number would include helicopters though?

I would take those numbers with a huge chunk of salt though.

First we'd have to decide how max sortie rate should be measured. Highest day to day operation or highest in theory?

Hi,

how many more years Liaoning can keep on going with the new inductions,

and during these 12 years it’s already been upgraded or there is certain number

of years before they upgrade and refit all of it again

thank you

It already completed MLU near the start of this year.

Importantly another mockup also started to appear on carrier Liaoning . The first PLAN aircraft carrier, commissioned in 2012, was then just completing her midlife refit (MLU) and has since completed a first post-MLU sea trial.

Those are all quite good sortie numbers, per 24 planes. USN would struggle to do better over a similar time period. Sure, there were USN exercises in the past where 2 per day were hit, one instance where 4 per day was hit, but that was a specific outlier. USN averages are very much in this shown bracket.

Wasn't the 4 a day some really unrealistic of just flying out and bombing a place 100kmish away and the coming back, and then repeat, or something like that lol.Those are all quite good sortie numbers, per 24 planes. USN would struggle to do better over a similar time period. Sure, there were USN exercises in the past where 2 per day were hit, one instance where 4 per day was hit, but that was a specific outlier. USN averages are very much in this shown bracket.

It was. With extra crew as well. It was basically artificially set up.Wasn't the 4 a day some really unrealistic of just flying out and bombing a place 100kmish away and the coming back, and then repeat, or something like that lol.

Not necessarily true. When I was assigned with VS-33 on USS America(CV 66) in 1981. It was not uncommon for some of our aircraft to have 4 even more flight ops a day. That is a fact particularly when tracking Soviet subs.It was. With extra crew as well. It was basically artificially set up.

Now on to sortie rate..The PLAN sortie rate seems fine. But I have to ask are they dropping ordnance? What sort of missions were being flown?

Those are all quite good sortie numbers, per 24 planes. USN would struggle to do better over a similar time period.

Really?

In July 1997... USS Nimitz (CVN 68) with Commander, Carrier Group Seven (CCG-7) and Carrier Airwing Nine embarked began a high intensity strike campaign. When they completed flight operations four days later, they had generated 771 strike sorties and had put 1,336 bombs on target....

The Surge, as it has come to be known, was unprecedented. It demonstrated the entire process required to put bombs on target in a littoral warfare scenario; it incorporated all facets of strike warfare – from weapons buildup in the magazines to bombs on target. In the post-Vietnam era, no other carrier and embarked airwing have ever generated as much firepower in ninety-eight hours.

The Center for Naval Analysis monitored JTFEX 97-2 and carefully studied the scenario described above, which comes from the introduction of this CNA paper USS Nimitz and Carrier Air Wing Nine Surge Demonstration dated April 1998. “Surge 97″, as it was called, was preceded by six days of an intense, event-driven scenario in which the entire Nimitz battle group conducted offensive and defensive operations. During these six days USS Nimitz and CVW-9 generated about 700 fixed-wing sorties.

Following that six-day period, operations paused for 16 hours, and USS Nimitz and CVW-9 made several preparations for “The Surge” including personnel augmentation, planning augmentation, and replenishment to insure the carrier was fully prepared for the exercise. The resulting average of 192 sorties was touted by the Navy as the benchmark for carrier operations. At the time, this was very important, because naval aviation had taken a hit following the 1991 Gulf War with critics citing low aircraft carrier sortie rates as a reason to reduce the number of aircraft carriers.

While there were obviously agendas at play for the exercise, the lessons learned from that exercise have clearly been demonstrated in Kosovo, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom in which, during these operations naval aviation has certainly redeemed itself of the skepticism that may have lingered from the Gulf War. In fact, it was “Surge 97″ that highlighted the remarkable reliability of the F-18 Hornet, a significant metric that highlights the high durability and high sustainability of the aircraft. However, in order for the USS Nimitz to achieve the daily 197 sortie rate sustained for 5 straight days of 24/7 flight operations, almost all sorties were conducted a range less than 200 nautical miles, with a large number conducted under 100nms. As real world operations have since demonstrated, that is not realistic. Regardless, sortie rates under strict conditions remain very useful for comparison purposes.

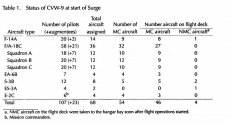

For “Surge 97″ USS Nimitz had 14 F-14As, 36 F/A-18Cs, 4 EA-6Bs, 8 S-3Bs, 2 ES-3As, and 4 E-2Cs, but of those aircraft only 9 F-14As, 32 F/A-18Cs, 4 EA-6Bs, 5 S-3Bs, 0 ES-3As, and 4 E-2Cs were mission capable on the first day. I think it is important to note that in real world operations, in this case an aircraft carrier that had been engaged in six days of intense operations, an aircraft carrier could have 20% of her CVW unavailable for operations. I think it is also noteworthy that the older aircraft, F-14s and S-3s, suffered the higher downtime rates.

Aircraft carrier sortie rates have varied since 1997. In 2001 the Navy claimed that Nimitz class carriers can support 207 sorties per day, and in 2004 the Navy claimed Nimitz class carriers could launch 230 total surge sorties per 24-hour flying day for four days. These sortie rates are limited to 200 nautical miles, require some preparation, and cannot be sustained beyond only a few days. Current doctrine and planning operates 2 CVNs together, each carrier supporting 120 sorties per 12 hour flight day, combining for 240 sorties over 24 hour days for extended periods of time.

CVL concept

Why is this important? Because sortie generation is one of, if not the most important metric for naval aviation capabilities, and seems to be one of the first aspects of carrier aviation ignored by critics of big deck nuclear aircraft carriers. For example, take the idea of a CVL, a 30,000 ton light carrier alternative supporting 20 F-35Bs. Let us be super optimistic, and suggest the F-35B is as reliable as the F/A-18C from a maintenance perspective (maybe a very patient aviator can explain to the peanut gallery why this is a super optimistic suggestion). In Surge 97, the F/A-18C achieved the eye popping sortie rate of 4.5 sorties per day, but N88 planning factors for the F/A-18C is 2.0 sorties per day. For the purposes of this exercise, let us assume the F-35B can support 2.0 sorties per day on a CVL.

If we assume 20% of the aircraft are not mission capable, and we should because that is how Murphy’s Law works on an aircraft carrier, we now have a CVL supporting 16 F-35Bs capable of conducting 32 sorties per day at a 2.0 sortie rate, and doing so without the services of carrier based E-2D or EA-18G. If a Nimitz class can support 120 sorties per day, we would need 4 CVLs to match the number of sorties a single CVN can support, and a CVN comes with E-2Ds and EA-18Gs built in. The Ford class, which is not only less expensive to operate than a Nimitz, but is specifically designed to support higher sortie generation rates, is probably going to average $8.5 billion over its lifetime (I am guessing, but using CBO numbers to guess). That means the Navy would have to build 30,000 ton CVLs at a cost under $2.2 billion each, which would be at a cost less than the 9,800 ton DDG-51 destroyer in the FY2010 budget, in order to be less expensive and equally capable in sortie generation as a Ford class.

I hate to break it to the CVL / Small Carrier crowd, but it is 100% MYTH and FUD when it is claimed that big deck nuclear aircraft carriers are somehow inferior to alternatives, including on the cost metric. They are in fact, superior in every costing, capacity, and capability metric one can find. The only consideration where CVLs have a good argument is in terms of risk, because CVNs put a lot of eggs in one basket. It all comes down to the level of risk that is acceptable vs the level of cost, capacity, and capability desired for your naval force. I’ll take the big deck, at least 10 if possible, with its associated conventional launch capability and with the E-2D and EA-18G, I’ll whip any 4 VSTOL CVLs every single day of the century.

It is not appropriate to compare it with the CV68 exercise in July 1997.Not necessarily true. When I was assigned with VS-33 on USS America(CV 66) in 1981. It was not uncommon for some of our aircraft to have 4 even more flight ops a day. That is a fact particularly when tracking Soviet subs.

Now on to sortie rate..The PLAN sortie rate seems fine. But I have to ask are they dropping ordnance? What sort of missions were being flown?

Really?

In July 1997... USS Nimitz (CVN 68) with Commander, Carrier Group Seven (CCG-7) and Carrier Airwing Nine embarked began a high intensity strike campaign. When they completed flight operations four days later, they had generated 771 strike sorties and had put 1,336 bombs on target....

That was an exercise in which the number of pilots and maintenance personnel far exceeded the normal number in order to reflect the dispatch rate, and a large number of close-range missions were specially selected.

This even made the think tank RAND Corporation believe in its analysis that it was an exercise for the sake of exercise, which was not in line with the actual situation.

The number of pilots increased by nearly a quarter

In the mission type, set close-range AI and CAS as the main mission

553 missions were conducted with targets within 100 nautical miles of the carrier,

214 missions were conducted between 100 and 200 nautical miles,

64 missions were conducted over 200 nautical miles.

RAND Corporation disagreed with the results of the exercise, believing it to be unrealistic.

So what? It is normal for air wings to beef up for high tempo operations. Normal. I know..I've experienced that. I served on five USN CVs.That was an exercise in which the number of pilots and maintenance personnel far exceeded the normal number in order to reflect the dispatch rate, and a large number of close-range missions were specially selected.

Rand is just a think tank..number crunchers. How many Rand personnel were aboard Nimitz during the exercise?..I bet the number is zero.

There is a big difference between real world experience and number crunching.

Yes, of course it can be enhanced.So what? It is normal for air wings to beef up for high tempo operations. Normal. I know..I've experienced that. I served on five USN CVs.

Rand is just a think tank..number crunchers. How many Rand personnel were aboard Nimitz during the exercise?..I bet the number is zero.

There is a big difference between real world experience and number crunching.

However, you are now comparing the enhanced special situation deployment intensity with the state of CV-17 during normal training, which is meaningless.