You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chinese semiconductor industry

- Thread starter Hendrik_2000

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

WSJ coverage on Gerald Yin of AMEC.

Here is the .

By

Nov. 9, 2022 5:30 am ET

Semiconductor whiz Gerald Yin left the U.S. and spent 18 years in China building what he said would be a worldwide powerhouse in chip-making equipment. Now the American citizen’s lifework has been thrown into uncertainty as undermine the global industry integration he celebrated.

Mr. Yin’s company, Inc., or AMEC, had been making big strides and was gunning for industry leaders based in the U.S. and Japan when Washington stepped in. Decades younger than its rivals, the Chinese maker of etching equipment and other tools for the semiconductor industry has said it picked up customers including Robert Bosch GmbH and U.S. chip maker Inc. Its equipment is used on dozens of production lines in Europe and Asia.

Then, the U.S. in October, the country’s biggest salvo against China’s tech industry so far. The new rules blocked China’s advanced-chip-development industry from access to U.S. technology as well as .

The Biden administration said the rules were aimed at keeping American chips . Their wide sweep may further bifurcate global supply chains and stymie China’s broader chip industry, setting it back years in efforts to catch up with more advanced U.S. and Asian rivals.

The new rules threaten AMEC in several ways. Of roughly 20 top managers and engineers at the Shanghai-based company, Mr. Yin and six others are U.S. citizens, according to the company’s latest annual report.

AMEC’s production could also be hampered by lack of access to U.S. or other countries’ parts and materials. And non-Chinese customers may shy away from equipment made by a company held up as a flag-bearer of Beijing’s chip ambitions.

Mr. Yin said in a recent earnings call that about 60% of the components and materials AMEC uses in its major products are made in China, suggesting that it relies on imports for nearly 40%. AMEC said in its 2021 annual report that it procured some materials from the U.S. but described that as a low percentage of the total.

The company’s signature products are etching tools, which help carve out circuit patterns onto a semiconductor wafer, a key step in the manufacturing process.

AMEC and Mr. Yin didn’t respond to questions. The company said on Chinese social media on Oct. 25 that it was operating normally so far and that its development was “stable, healthy and safe.” It said it abided by laws and regulations wherever it operates.

On AMEC’s social-media account on Oct. 28, Mr. Yin said the company aimed to develop into an international leader.

Born in China, Mr. Yin attended prestigious schools in the country and earned a doctorate from the University of California, Los Angeles, before embarking on a U.S. semiconductor career.

Two U.S. companies— Inc. and Corp. —are leaders in etching, and Mr. Yin, AMEC’s founder, worked at both. Those two, plus Ltd. , accounted for 91% of the worldwide dry-etch-system market in 2021, according to consulting firm Inc.

In 2004, Mr. Yin was 60 years old and thinking of retirement when a middle-school classmate who was a government official in China invited him to come home, according to a 2019 report by the state-owned Xinmin Evening News.

“It was time to make a contribution to the motherland and its people,” the paper quoted Mr. Yin as saying. The report said he took a group of 15 experts with him to Shanghai.

Early investors in AMEC included Inc., U.S.-based venture-capital fund Walden International and an arm of South Korea’s Samsung Group. The company’s biggest shareholder is an investment arm of the Shanghai government, and the No. 2 shareholder is an entity controlled by a national semiconductor-investment fund, according to Chinese corporate-registry databases. It also receives government research subsidies.

Within three years of returning to China, Mr. Yin and his team developed their first etching machine. This was the first time that China was able to make such high-end competitive semiconductor equipment, according to state media reports.

Domestically, social-media commentators called the company a potential national champion that would help China’s chip industry achieve self-sufficiency.

By 2015, AMEC had gotten far enough that the Commerce Department ended export controls of certain American etching machines to China because it said machines of comparable quality were already available from a Chinese source. Mr. Yin said at a technology forum in Shanghai in 2018 that the department was talking about his company’s products.

The success didn’t come without controversy. There was a 2007 lawsuit in a California federal court by Applied Materials alleging AMEC misappropriated trade secrets. Mr. Yin, who was named as a defendant, told Chinese media he didn’t do anything wrong. The companies settled their litigation in 2010.

Another lawsuit alleging patent infringement—this one filed in Taiwan by Lam Research against AMEC—was dismissed in 2009 by Taiwan’s Intellectual Property Court.

As the company and U.S.-China tensions grew, Chinese social media’s depiction of Mr. Yin as a hometown champion striking fear into the West prompted the company to respond. In a 2020 statement, AMEC said the stories about Mr. Yin were exaggerated.

In August, Mr. Yin said AMEC was based on the idea of China and everyone else being part of the same global industry.

“We would only be able to cover 15% of the global market at most if we only focus on the domestic market, so we have to carry forward a strategy to develop globally,” he said.

Here is the .

Entrepreneur Caught in the Middle of U.S.-China Chip War

An American’s vision to build a global semiconductor player in China is clouded by moves to restrict supply chain

By

Nov. 9, 2022 5:30 am ET

Semiconductor whiz Gerald Yin left the U.S. and spent 18 years in China building what he said would be a worldwide powerhouse in chip-making equipment. Now the American citizen’s lifework has been thrown into uncertainty as undermine the global industry integration he celebrated.

Mr. Yin’s company, Inc., or AMEC, had been making big strides and was gunning for industry leaders based in the U.S. and Japan when Washington stepped in. Decades younger than its rivals, the Chinese maker of etching equipment and other tools for the semiconductor industry has said it picked up customers including Robert Bosch GmbH and U.S. chip maker Inc. Its equipment is used on dozens of production lines in Europe and Asia.

Then, the U.S. in October, the country’s biggest salvo against China’s tech industry so far. The new rules blocked China’s advanced-chip-development industry from access to U.S. technology as well as .

The Biden administration said the rules were aimed at keeping American chips . Their wide sweep may further bifurcate global supply chains and stymie China’s broader chip industry, setting it back years in efforts to catch up with more advanced U.S. and Asian rivals.

The new rules threaten AMEC in several ways. Of roughly 20 top managers and engineers at the Shanghai-based company, Mr. Yin and six others are U.S. citizens, according to the company’s latest annual report.

AMEC’s production could also be hampered by lack of access to U.S. or other countries’ parts and materials. And non-Chinese customers may shy away from equipment made by a company held up as a flag-bearer of Beijing’s chip ambitions.

Mr. Yin said in a recent earnings call that about 60% of the components and materials AMEC uses in its major products are made in China, suggesting that it relies on imports for nearly 40%. AMEC said in its 2021 annual report that it procured some materials from the U.S. but described that as a low percentage of the total.

The company’s signature products are etching tools, which help carve out circuit patterns onto a semiconductor wafer, a key step in the manufacturing process.

AMEC and Mr. Yin didn’t respond to questions. The company said on Chinese social media on Oct. 25 that it was operating normally so far and that its development was “stable, healthy and safe.” It said it abided by laws and regulations wherever it operates.

On AMEC’s social-media account on Oct. 28, Mr. Yin said the company aimed to develop into an international leader.

Born in China, Mr. Yin attended prestigious schools in the country and earned a doctorate from the University of California, Los Angeles, before embarking on a U.S. semiconductor career.

Two U.S. companies— Inc. and Corp. —are leaders in etching, and Mr. Yin, AMEC’s founder, worked at both. Those two, plus Ltd. , accounted for 91% of the worldwide dry-etch-system market in 2021, according to consulting firm Inc.

In 2004, Mr. Yin was 60 years old and thinking of retirement when a middle-school classmate who was a government official in China invited him to come home, according to a 2019 report by the state-owned Xinmin Evening News.

“It was time to make a contribution to the motherland and its people,” the paper quoted Mr. Yin as saying. The report said he took a group of 15 experts with him to Shanghai.

Early investors in AMEC included Inc., U.S.-based venture-capital fund Walden International and an arm of South Korea’s Samsung Group. The company’s biggest shareholder is an investment arm of the Shanghai government, and the No. 2 shareholder is an entity controlled by a national semiconductor-investment fund, according to Chinese corporate-registry databases. It also receives government research subsidies.

Within three years of returning to China, Mr. Yin and his team developed their first etching machine. This was the first time that China was able to make such high-end competitive semiconductor equipment, according to state media reports.

Domestically, social-media commentators called the company a potential national champion that would help China’s chip industry achieve self-sufficiency.

By 2015, AMEC had gotten far enough that the Commerce Department ended export controls of certain American etching machines to China because it said machines of comparable quality were already available from a Chinese source. Mr. Yin said at a technology forum in Shanghai in 2018 that the department was talking about his company’s products.

The success didn’t come without controversy. There was a 2007 lawsuit in a California federal court by Applied Materials alleging AMEC misappropriated trade secrets. Mr. Yin, who was named as a defendant, told Chinese media he didn’t do anything wrong. The companies settled their litigation in 2010.

Another lawsuit alleging patent infringement—this one filed in Taiwan by Lam Research against AMEC—was dismissed in 2009 by Taiwan’s Intellectual Property Court.

As the company and U.S.-China tensions grew, Chinese social media’s depiction of Mr. Yin as a hometown champion striking fear into the West prompted the company to respond. In a 2020 statement, AMEC said the stories about Mr. Yin were exaggerated.

In August, Mr. Yin said AMEC was based on the idea of China and everyone else being part of the same global industry.

“We would only be able to cover 15% of the global market at most if we only focus on the domestic market, so we have to carry forward a strategy to develop globally,” he said.

More crap from the WSJ. No surprises there. You can almost sense the McCarthyistic crap of the author, like if Yin is somehow a Chinese Bin Laden of some sort. "Hey boys, lets add this two unsuccessful lawsuits to add to the evilness of the guy" "Is he evil now?"WSJ coverage on Gerald Yin of AMEC.

Here is the .

Entrepreneur Caught in the Middle of U.S.-China Chip War

An American’s vision to build a global semiconductor player in China is clouded by moves to restrict supply chain

By

Nov. 9, 2022 5:30 am ET

Semiconductor whiz Gerald Yin left the U.S. and spent 18 years in China building what he said would be a worldwide powerhouse in chip-making equipment. Now the American citizen’s lifework has been thrown into uncertainty as undermine the global industry integration he celebrated.

Mr. Yin’s company, Inc., or AMEC, had been making big strides and was gunning for industry leaders based in the U.S. and Japan when Washington stepped in. Decades younger than its rivals, the Chinese maker of etching equipment and other tools for the semiconductor industry has said it picked up customers including Robert Bosch GmbH and U.S. chip maker Inc. Its equipment is used on dozens of production lines in Europe and Asia.

Then, the U.S. in October, the country’s biggest salvo against China’s tech industry so far. The new rules blocked China’s advanced-chip-development industry from access to U.S. technology as well as .

The Biden administration said the rules were aimed at keeping American chips . Their wide sweep may further bifurcate global supply chains and stymie China’s broader chip industry, setting it back years in efforts to catch up with more advanced U.S. and Asian rivals.

The new rules threaten AMEC in several ways. Of roughly 20 top managers and engineers at the Shanghai-based company, Mr. Yin and six others are U.S. citizens, according to the company’s latest annual report.

AMEC’s production could also be hampered by lack of access to U.S. or other countries’ parts and materials. And non-Chinese customers may shy away from equipment made by a company held up as a flag-bearer of Beijing’s chip ambitions.

Mr. Yin said in a recent earnings call that about 60% of the components and materials AMEC uses in its major products are made in China, suggesting that it relies on imports for nearly 40%. AMEC said in its 2021 annual report that it procured some materials from the U.S. but described that as a low percentage of the total.

The company’s signature products are etching tools, which help carve out circuit patterns onto a semiconductor wafer, a key step in the manufacturing process.

AMEC and Mr. Yin didn’t respond to questions. The company said on Chinese social media on Oct. 25 that it was operating normally so far and that its development was “stable, healthy and safe.” It said it abided by laws and regulations wherever it operates.

On AMEC’s social-media account on Oct. 28, Mr. Yin said the company aimed to develop into an international leader.

Born in China, Mr. Yin attended prestigious schools in the country and earned a doctorate from the University of California, Los Angeles, before embarking on a U.S. semiconductor career.

Two U.S. companies— Inc. and Corp. —are leaders in etching, and Mr. Yin, AMEC’s founder, worked at both. Those two, plus Ltd. , accounted for 91% of the worldwide dry-etch-system market in 2021, according to consulting firm Inc.

In 2004, Mr. Yin was 60 years old and thinking of retirement when a middle-school classmate who was a government official in China invited him to come home, according to a 2019 report by the state-owned Xinmin Evening News.

“It was time to make a contribution to the motherland and its people,” the paper quoted Mr. Yin as saying. The report said he took a group of 15 experts with him to Shanghai.

Early investors in AMEC included Inc., U.S.-based venture-capital fund Walden International and an arm of South Korea’s Samsung Group. The company’s biggest shareholder is an investment arm of the Shanghai government, and the No. 2 shareholder is an entity controlled by a national semiconductor-investment fund, according to Chinese corporate-registry databases. It also receives government research subsidies.

Within three years of returning to China, Mr. Yin and his team developed their first etching machine. This was the first time that China was able to make such high-end competitive semiconductor equipment, according to state media reports.

Domestically, social-media commentators called the company a potential national champion that would help China’s chip industry achieve self-sufficiency.

By 2015, AMEC had gotten far enough that the Commerce Department ended export controls of certain American etching machines to China because it said machines of comparable quality were already available from a Chinese source. Mr. Yin said at a technology forum in Shanghai in 2018 that the department was talking about his company’s products.

The success didn’t come without controversy. There was a 2007 lawsuit in a California federal court by Applied Materials alleging AMEC misappropriated trade secrets. Mr. Yin, who was named as a defendant, told Chinese media he didn’t do anything wrong. The companies settled their litigation in 2010.

Another lawsuit alleging patent infringement—this one filed in Taiwan by Lam Research against AMEC—was dismissed in 2009 by Taiwan’s Intellectual Property Court.

As the company and U.S.-China tensions grew, Chinese social media’s depiction of Mr. Yin as a hometown champion striking fear into the West prompted the company to respond. In a 2020 statement, AMEC said the stories about Mr. Yin were exaggerated.

In August, Mr. Yin said AMEC was based on the idea of China and everyone else being part of the same global industry.

“We would only be able to cover 15% of the global market at most if we only focus on the domestic market, so we have to carry forward a strategy to develop globally,” he said.

Bojie shares: The company's semiconductor related equipment has just come out of the prototype and is undergoing on-site testing and verification with customers

Jiwei.com News Recently, Bojie shares said in an institutional survey that the company's semiconductor-related equipment has just come out of the prototype, and it is conducting on-site testing and verification with customers.

Bojie Co., Ltd. has been doing in-depth technology development and layout in the field of testing and inspection. The company will carry out in-depth research and development and layout along the three core technical capabilities of robot software algorithms, operation control capabilities, and AOI visual inspection artificial intelligence. On the basis of these three capability frameworks, the company will actively meet the needs of downstream customers to deploy some functional modules, such as optical, acoustic, electrical, radio frequency and other test fields.

On the second growth curve, the company's layout in the MLCC and semiconductor fields has achieved initial results. Among them, Ordewei has achieved technological breakthroughs in the MLCC field and accumulated good orders. At present, the company has made further layouts for testing machines. In the future The company will continue to follow the MLCC upstream and downstream processes to achieve equipment coverage and capacity improvement; there are prototypes in the semiconductor field, one is the front wafer surface defect detection and flatness inspection, the other is sorting equipment, and there are also acquisitions. A semiconductor dicing machine company.

Bojie shares said that the company's layout in the MLCC field has been relatively long and relatively mature. This year, the company's equipment in the MLCC field will be shipped normally. Due to the impact of downstream market fluctuations, there will be delays in order confirmation and revenue confirmation.

On the whole, the company will focus more on the research and development of new equipment such as laminators and testing machines this year. The value of new equipment accounts for more than half of the MLCC process equipment, which belongs to the core capital expenditure and Technically difficult equipment. The new equipment is currently expected to enter customer sites for testing in the fourth quarter. With the increase of the company's product series in the MLCC field, it will provide new growth points for the company's future performance.

It further stated that the company's related equipment in the MLCC and semiconductor fields belongs to the high-end manufacturing independent and controllable field. Among them, with the continuous improvement of the complexity of electronic products, the demand for MLCC will continue to increase, which will lead to a larger equipment market demand in the downstream market. According to the company's market demand for two or three products, it is expected that there will be hundreds of billion-level demand. There are many relevant research reports in the market for the market volume of semiconductor equipment for reference.

Guangliwei: WAT test equipment business has shown explosive growth in the past two years

Jiwei.com News Recently, Guangliwei said in an institutional survey that the slight fluctuation in the company's comprehensive gross profit margin is mainly due to changes in the sales structure of software and hardware products. The company's software product gross profit margin is generally close to or equal to 100% , the gross profit margin of hardware products is around 50%~60%, so when the rapid increase in test equipment in the short term increases the proportion of its business revenue, the company's overall gross profit margin will decline.

The main reason for the change in the proportion of the company's software and hardware business revenue is that the company's WAT test equipment has only begun to enter the fab mass production line on a large scale in the past two years. Compared with the company's EDA software business, its sales base is small, and The test equipment has the characteristics of high unit price and relatively short promotion period after verification, so it has shown an explosive growth trend in the past two years. In the medium and long-term outlook, the company's product and technology layout on the software side will break through the existing growth rate and keep pace with equipment products after a period of innovative R&D and market expansion applications. While improving the company's software and hardware integration solutions, Together, we will help the company's business grow steadily.

At present, Guangliwei's investment in product and technology research and development continues to increase. As of the end of September, the total number of personnel is nearly 300. Later, with the deepening of research and development, the team will be further expanded. In terms of personnel structure, the company basically maintains that nearly 80% of the personnel are R&D personnel, and the production personnel account for more than 80% after combined calculation. In the future, the company will reasonably plan the proportion and increase of personnel in software and hardware according to the research projects, the number of orders and customer expansion, so as to ensure high-quality R&D output and customer support services.

Regarding the company's EDA software research and development progress, Guangliwei said, first of all, the company's yield improvement software belongs to manufacturing EDA software, so it is closely related to the application scenario of the product. The company continues to pay attention to customer demand feedback, and also from the company's software. In the technical development service, the functional modules of the software are continuously expanded horizontally, and the technical depth of the products is vertically optimized; secondly, the company is continuously increasing R&D investment and attracting outstanding talents to join the extended R&D work of manufacturing EDA product categories, such as manufacturability Design related tools, yield analysis and management systems and other software to create higher technical barriers, improve the company's core competitive advantage, and help the company's future business to form a more systematic product and market ecology.

With the increasing complexity of integrated circuit process, the company has seen the important value of data analysis for the upstream and downstream enterprises of integrated circuits in the long-term yield improvement business. Therefore, the company has invested more manpower and material resources in research and development in this field in the past two years. products, especially this year, the company has made great progress in product development.

Following the launch of the DE-G product, a generalized analysis tool for semiconductors, in 2021, as of now, Guangliwei has developed the first version products of the integrated circuit yield analysis and management system DE-YMS and the integrated circuit defect management system DE-DMS, and is in the process of developing them. Developed DE-FDC, an abnormality monitoring and classification system for semiconductor equipment.

My guess is SMIC have >90% yields on 14nm FinFET and have also attained mass production of SMIC N+1 (10/12nm FinFET) with reasonable yield. We also know SMIC have produced those small SMIC N+2 (7nm FinFET) cryptocurrency mining chips but I suspect the yields on those are probably not up to scratch yet. Plus without EUV the cost competitiveness of the 7nm node is kind of questionable. If your customer cannot buy outside of China the cost disadvantage might be kind of irrelevant, but the thing is SMIC is still trying to avoid further US sanctions, so it is not like they will accept just any customer I think.this is the first time they've used FinFET rather than 14nm has the most advanced process they do. It's been 14nm since 2019. I think they are finally moved on to really producing N+1 process in Q3. For the past 3 years, they've been raising yield on 14nm and maybe 12nm + trialed production of N+1 chips.

Last edited:

Well, SMIC produces chips for Phytium, which is on the entity list. So, they can't be that afraid of US sanctions. Especially given the current sanctions already applied on them.

Moore Threads S80 will be going on sale on JD.com on 11/11 with pricing of 1970 RMB.

They are cooperating with Siland and Pyou? (蔚领时代) for cloud gaming

From their website, looks like they are partnered with several services like AliCloud for providing gaming on cloud.

Moore threads has now completed level 1 compatibility with Baidu PaddlePaddle platform. Not bad, IIRC Kunluns is at level 3 compatibility already (), so Moore threads still has some room to go here.

Also, signed an agreement with OpenMMLab

which seems to be an open source system for machine learning.

On separate news, YMTC TiPlus7100 is now on sale for 649 RMB (1TB). There are also 512 GB and 2 TB version.

Moore Threads S80 will be going on sale on JD.com on 11/11 with pricing of 1970 RMB.

They are cooperating with Siland and Pyou? (蔚领时代) for cloud gaming

From their website, looks like they are partnered with several services like AliCloud for providing gaming on cloud.

Moore threads has now completed level 1 compatibility with Baidu PaddlePaddle platform. Not bad, IIRC Kunluns is at level 3 compatibility already (), so Moore threads still has some room to go here.

Also, signed an agreement with OpenMMLab

which seems to be an open source system for machine learning.

On separate news, YMTC TiPlus7100 is now on sale for 649 RMB (1TB). There are also 512 GB and 2 TB version.

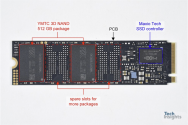

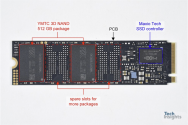

"According to YMTC’s press release about Xtacking 3.0, the technology can be found in every version of the TiPlus7100 high-speed SSD. TechInsights purchased the 512GB and the 1TB; the 2TB is not yet available for purchase.

TechInsights has not yet found Xtacking 3.0 inside any of the models of the TiPlus7100 that we have torn down. The dies TechInsights has evaluated so far:

...

There are eight NAND dies (die marking of CDT2A) within each NAND package. The CDT2A die has a layout of 2×2 plane ... . This is different from the previous YMTC 128L die layout ... which had a 1x4 plane. TechInsights' analysis revealed that the new YMTC CDT2A die is in fact a YMTC 128-Layer 3D NAND, with total gates count of 141 ... ."

TechInsights has not yet found Xtacking 3.0 inside any of the models of the TiPlus7100 that we have torn down. The dies TechInsights has evaluated so far:

- Are 128L ..., not 232L

- Include a die layout of 2x2 plane ..., not 3x2 as YMTC has described

- Do not include Xtacking 3.0 features, such as the back side source connect (BSSC) or the center X-decoder.

...

There are eight NAND dies (die marking of CDT2A) within each NAND package. The CDT2A die has a layout of 2×2 plane ... . This is different from the previous YMTC 128L die layout ... which had a 1x4 plane. TechInsights' analysis revealed that the new YMTC CDT2A die is in fact a YMTC 128-Layer 3D NAND, with total gates count of 141 ... ."

Last edited:

Even local supplier you need to pre-order 1 year in advance.If I'm reading this correctly, the explanation is for prepayment of early delivery (提前下單) of long term contract. I can only assuming that they are speeding up the delivery of non-Chinese equipments.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.