China’s Premier Wen Says Property Curbs to Stay, Reiterates Fine-Tuning

China’s Premier Wen Jiabao reiterated that the government will maintain curbs on the property market to bring prices down to a reasonable level and economic policies will be “fine-tuned” to support growth.

Wen also repeated his call to strengthen credit support to the “real economy” and small and medium-sized companies. His comments, posted on the central government’s website, were made at a meeting of the State Council today to discuss its work report to the National People’s Congress in March.

China’s growth is moderating as Europe’s debt crisis and weak U.S. expansion hurt exports and the government’s campaign to rein in inflation and property prices damps output. The nation’s first official data for 2012 due tomorrow may show manufacturing contracted in January, adding to pressure on the government to step up policy easing.

“We must maintain keen observation and make accurate judgments about the domestic and external economic situations and be on high alert for any signs or trends in the economy,” Wen said at the meeting, according to the statement. The government will “properly manage the strength, pace and focus of macro-controls, and fine-tune policies at the appropriate time and with appropriate intensity,” he said.

The central bank held off on a reduction in bank reserve requirements that some economists had predicted would come before a weeklong holiday that ended on Jan. 28, suggesting officials are cautious on more monetary loosening. The People’s Bank of China has added cash into the financial system through reverse-repurchase operations to support lending.

Curb Speculation

The government will ensure funding for key projects under construction and maintain steady growth in investment, he said.

“We will consolidate the results of property controls, continue to strictly implement and gradually improve policy measures aimed at curbing speculative demand and push prices to return to reasonable levels,” he said.

Wen said in October the government will “fine-tune” economic policies as needed amid a deteriorating global outlook and reiterated the pledge on Jan. 3, describing business conditions this quarter as “relatively difficult.”

A manufacturing purchasing managers’ index probably dropped below a reading of 50 that divides expansion from contraction for the second time in three months, according to the median estimate of 17 economists in a Bloomberg News survey. The data will be released in Beijing tomorrow by the statistics bureau and logistics federation.

Wen also pledged the government will work to “effectively solve prominent problems affecting people’s well-being” and make sure that welfare payments such as the minimum living guarantee and unemployment insurance are linked to inflation.

---------- Post added at 02:46 PM ---------- Previous post was at 02:38 PM ----------

Sany, Citic to Pay $475 Million for German Cement-Pump Maker Putzmeister

Sany Heavy Industry Co. headed by China’s richest man, and a partner will pay 360 million euros ($475 million) for concrete-pump maker Putzmeister Holding GmbH to add technology and expand overseas.

The Chinese construction-equipment maker will buy 90 percent of Putzmeister for 324 million euros and Citic PE Advisors (Hong Kong) Ltd. will purchase the balance, it said in a Shanghai stock exchange statement yesterday. The deal may be completed by March 1, pending regulatory approvals, the Changsha, China-based company said.

Sany climbed to the highest in more than two months in Shanghai trading after announcing the deal and saying that profit probably rose more than 60 percent last year. Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science & Technology Co. also plans to build a plant in the U.S. as Chinese construction-equipment makers seek to challenge Caterpillar Inc. and Komatsu Ltd. (6301) internationally.

“The Putzmeister brand will give Sany an appeal that it doesn’t have at the moment to customers in developed countries,” said Liu Rong, an analyst with China Merchants Securities Co. “This deal is also a milestone. Who could have imagined even a few years ago that a Chinese company would buy such a renowned firm?”

Burj Khalifa

Putzmeister, based in Aichtal, Germany, supplied pumps used to build Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, and ones that helped quell the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan last year. Sany plans to make Aichtal its headquarters for concrete machinery following the Putzmeister deal, it said in a Jan. 27 statement. Norbert Scheuch will remain head of Putzmeister under the new owner.

The German company, founded by Karl Schlecht, employs 3,000 people and probably had a profit of 6 million euros on sales of 560 million euros last year, Sany said. It’s being sold by shareholders Karl Schlecht Stiftung and Karl Schlecht Familienstiftung.

It took about two weeks for the two sides to agree on a deal, Sany Chairman Liang Wengen told reporters today at a briefing in Changsha. The company will pay for the acquisition from internal resources, said Vice Chairman Xiang Wenbo.

“With this deal, we’ve turned our most competitive international rival into one of us,” Xiang said. “It also reflects China’s rising position in the world’s construction- machinery industry.”

The Chinese company was advised on the deal by Bank of America Corp, while Morgan Stanley (MS) worked with Putzmeister.

China-Europe Deals

Chinese companies are making acquisitions overseas as they seek new technologies and as European companies struggle for funding amid a debt crisis. LDK Solar Co. (LDK), China’s second- largest solar panel maker, this month agreed to buy Germany’s Sunways AG (SWW), and Shandong Heavy Industry Group-Weichai Group agreed to acquire luxury-yacht builder Ferretti Group.

“The current debt crisis gives Chinese companies opportunities to buy,” Liu said.

Sany, controlled by Liang, climbed 1.6 percent to close at 14.21 yuan, the highest since Nov. 15. The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index rose 0.3 percent.

The company separately said profit probably rose last year after it sold more equipment and won market share. Net income was 5.61 billion yuan in 2010.

Construction growth has slowed in China as the government seeks to cool speculation and fend off a property bubble. Home sales (CHRESARE) rose at the slowest pace in three years in 2011, and expansion of investment in real estate slowed to 28 percent from 33 percent in 2010.

Sany, which makes excavators and concrete machinery, postponed a $3.3 billion planned initial Hong Kong sale last year, citing market conditions.

Liang topped Forbes Asia’s 2011 China rich list with an estimated wealth of $9.3 billion. The company’s three other founders are also billionaires, according to the magazine.

---------- Post added at 04:23 PM ---------- Previous post was at 02:46 PM ----------

The Global Stagnation and China

Five years after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–09 began there is still no sign of a full recovery of the world economy. Consequently, concern has increasingly shifted from financial crisis and recession to slow growth or stagnation, causing some to dub the current era the Great Stagnation.1 Stagnation and financial crisis are now seen as feeding into one another. Thus IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde declared in a speech in China on November 9, 2011, in which she called for the rebalancing of the Chinese economy:

The global economy has entered a dangerous and uncertain phase. Adverse feedback loops between the real economy and the financial sector have become prominent. And unemployment in the advanced economies remains unacceptably high. If we do not act, and act together, we could enter a downward spiral of uncertainty, financial instability, and a collapse in global demand. Ultimately, we could face a lost decade of low growth and high unemployment.

To be sure, a few emerging economies have seemingly bucked the general trend, continuing to grow rapidly—most notably China, now the world’s second largest economy after the United States. Yet, as Lagarde warned her Chinese listeners, “Asia is not immune” to the general economic slowdown, “emerging Asia is also vulnerable to developments in the financial sector.” So sharp were the IMF’s warnings, dovetailing with widespread fears of a sharp Chinese economic slowdown, that Lagarde in late November was forced to reassure world business, declaring that stagnation was probably not imminent in China (the Bloomberg.com headline ran: “IMF Sees Chinese Economy Avoiding Stagnation.”)3

Nevertheless, concerns regarding the future of the Chinese economy are now widespread. Few informed economic observers believe that the current Chinese growth trend is sustainable; indeed, many believe that if China does not sharply alter course, it is headed toward a severe crisis. Stephen Roach, non-executive chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, argues that China’s export-led economy has recently experienced two warning shots: first the decline beginning in the United States following the Great Financial Crisis, and now the continuing problems in Europe. “China’s two largest export markets are in serious trouble and can no longer be counted on as reliable, sustainable sources of external demand.”4

In order to avoid looming disaster, the current economic consensus suggests that the Chinese economy needs to rebalance its shares of net exports, investment, and consumption in GDP—moving away from an economy that is dangerously over-reliant on investment and exports, characterized by an extreme deficiency in consumer demand, and increasingly showing signs of a real estate/financial bubble. But the very idea of such a fundamental rebalancing—on the gigantic scale required—raises the question of contradictions that lie at the center of the whole low-wage accumulation model that has come to characterize contemporary Chinese capitalism, along with its roots in the current urban-rural divide.

Giving life to these abstract realities is the burgeoning public protest in China, now consisting of literally hundreds of thousands of mass incidents a year—threatening to halt or even overturn the entire extreme “market-reform” model.5 China’s reliance on its “floating population” of low-wage internal migrants for most export manufacture is a source of deep fissures in an increasingly polarized society. And connected to these economic and social contradictions—that include huge amounts of land seized from farmers—is a widening ecological rift in China, underscoring the unsustainability of the current path of development.

Nor are China’s contradictions simply internal. The complex system of global supply chains that has made China the world’s factory has also made China increasingly dependent on foreign capital and foreign markets, while making these markets vulnerable to any disruption in the Chinese economy. If a severe Chinese crisis were to occur it would open up an enormous chasm in the capitalist system as a whole. As the New York Times noted in May 2011, “The timing for when China’s growth model will run out of steam is probably the most critical question facing the world economy.”6 More important than the actual timing, however, are the nature and repercussions of such a slowdown.

Capitalist Contradictions with Chinese Characteristics

For many the idea that the Chinese economy is rife with contradictions may come as something as a surprise since the hype on Chinese growth has expanded more rapidly than the Chinese economy itself. As the Wall Street Journal sardonically queried in July 2011, “When exactly will China take over the world? The moment of truth seems to be coming closer by the minute. China will become the largest economy by 2050, according to HSBC. No, its 2040, say analysts at Deutsche Bank. Try 2030, the World Bank tells us. Goldman Sachs points to 2020 as the year of reckoning, and the IMF declared several weeks ago that China’s economy will push past America’s in 2016.” Not to be outdone, Harvard historian Niall Ferguson declared in his 2011 book, Civilization: The West and the Rest, that “if present rates persist China’s economy could surpass America’s in 2014 in terms of domestic purchasing power.”7

This prospect is generally viewed with unease in the old centers of world power. But at the same time the new China trade is an enormous source of profitability for the Triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan. The latest round of rapid growth that has enhanced China’s global role was an essential component of the recovery of global financialized capitalism from the severe crisis of 2007–09, and is counted on in the future.

There are clearly some who fantasize, in today’s desperate conditions, that China can carry the world economy on its back and keep the developed nations from what appears to be a generation of stagnation and intense political struggles over austerity politics.8 The hope here undoubtedly is that China could provide capitalism with a few decades of adequate growth and buy time for the system, similar to what the U.S.-led debt and financial expansion did over the past thirty years. But such an “alignment of the stars” for today’s world capitalist economy, based on the continuation of China’s meteoric growth, is highly unlikely.

“Let’s not get carried away,” the Wall Street Journal cautions us. “There’s a good deal of turmoil simmering beneath the surface of China’s miracle.” The contradictions it points to include mass protests (rising to as many as 280,000 in 2010), overinvestment, idle capacity, weak consumption, financial bubbles, higher prices for raw materials, rising food prices, increasing wages, long-term decline in labor surpluses, and massive environmental destruction. It concludes, “If nothing else, the colossal challenges that lie ahead for China provide an abundance of good reasons to doubt long-term projections of the country’s economic supremacy and global dominance.” The immediate future of China is therefore uncertain, throwing added uncertainty on the entire global economy. As we shall see, not only might China not bail out global capitalism at present, an argument can be made that it constitutes the single weakest link for the global capitalist chain.9

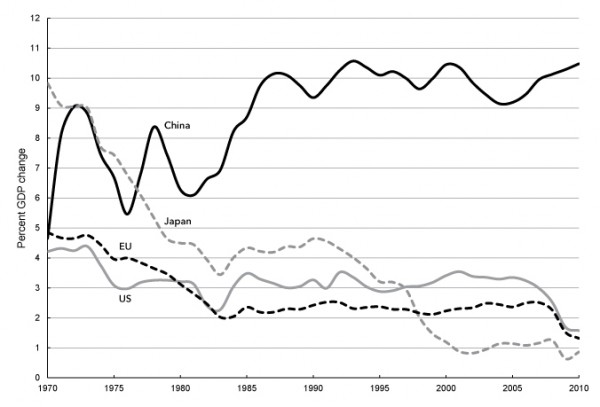

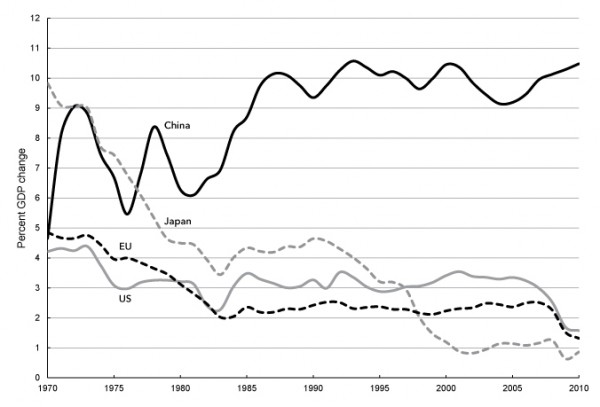

At question is the extraordinary rate of Chinese expansion, especially when compared with the economies of the Triad. The great divergence in growth rates between China and the Triad can be seen in Chart 1 (below), showing ten-year moving averages of annual real GDP growth for the United States, the European Union, and Japan, from 1970 to 2010. While the rich economies of the United States, Western Europe, and Japan have been increasingly prone to stagnation—overcoming this in 1980–2006 only by means of a series of financial bubbles—China’s economy over the same period (beginning in the Mao era) has continually soared. China managed to come out of the Great Financial Crisis period largely unaffected with a double-digit rate of growth, at the same time that what The Economist has dubbed “the moribund rich world” was laboring to achieve any positive growth at all.10

To give a sense of the difference that the divergence in growth rates shown in Chart 1 makes with respect to exponential growth, an economy growing at a rate of 10 percent will double in size every seven years or so, while an economy growing at 2 percent will take thirty-six years to double in size, and an economy growing at 1 percent will take seventy-two years.11

The economic slowdown in the developed, capital-rich economies is long-standing, associated with deepening problems of surplus capital absorption or overaccumulation. As the New York Times states, “Mature countries like the United States and Germany are lucky to grow about 3 percent annually”—indeed, today we might say lucky to grow at 2 percent. Japan’s growth rate has averaged less than 1 percent over the period 1992 to 2010. As Lagarde noted in a speech in September 2011, according to the latest IMF projections, “the advanced economies will only manage an anemic 1 1/2-2 percent” growth rate over the years 2011–12. China, in contrast, has been growing at 10 percent.12

The problems of the mature economies are complicated today by two further features: (1) the heavy reliance on financialization to lift the economy out of stagnation, but with the consequence that the financial bubbles eventually burst, and (2) the shift towards the corporate outsourcing of production to the global South. World economic growth in recent decades has gravitated to a handful of emerging economies of the periphery; even as the lion’s share of the profits derived from global production are concentrated within the capitalist core, where they worsen problems of maturity and stagnation in the capital-rich economies.13

As the structural crisis within the center of the capitalist world economy has deepened, the hope has been raised by some that China will serve to counterbalance the tendency toward stagnation at the global level. However, even as this hope has been raised it has been quickly dashed—as it has become increasingly apparent that cumulative contradictions are closing in on China’s current model, producing growing panic within world business.

Ironically, today’s fears regarding the Chinese economy stem in part from the way China engineered its way out of the global slump brought on by the Great Financial Crisis—a feat that was regarded initially by some as conclusive proof that China had “decoupled” itself from the West’s fate and represented an unstoppable growth machine. Faced with the world crisis and declining foreign trade, the Chinese government introduced a massive $585 billion stimulus plan in November 2008, and urged state banks aggressively to make new loans. Local governments in particular ran up huge debts associated with urban expansion and real estate speculation. As a result, the Chinese economy rebounded almost instantly from the crisis (in a V-shaped turnaround). The growth rate was 7.1 percent in the first half of 2009 with state-directed investments estimated as accounting for 6.2 percentage points of that growth.14 The means of accomplishing this was an extraordinary increase in fixed investment, which served to fill the gap left by falling exports.

This can be seen in Table 1, which shows the percent contribution to China’s GDP of consumption, investment, government, and trade (net exports). The sharp increase in investment as a share of GDP, which rose 7 percentage points between 2007–10, mirrored the sharp decrease in the share of both trade and consumption over the same period, which dropped 5 and 2 percentage points, respectively. Meanwhile, the share of government spending in GDP remained steady. Investment alone now constitutes 46 percent of GDP, while investment plus trade equals 52 percent.

Browse: Home / 2012, Volume 63, Issue 09 (February) / The Global Stagnation and China

Custom Search

Web

Dear Reader,

We place these articles at no charge on our website to serve all the people who cannot afford Monthly Review, or who cannot get access to it where they live. Many of our most devoted readers are outside of the United States. If you read our articles online and you can afford a subscription to our print edition, we would very much appreciate it if you would consider purchasing one. Please visit the MR store for subscription options. Thank you very much.

—Eds.

The Global Stagnation and China

John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney

Review of the Month more on Asia, Economics

1

John Bellamy Foster (jfoster [at] monthlyreview.org) is editor of Monthly Review and professor of Sociology at the University of Oregon. Robert W. McChesney (rwmcches [at] uiuc.edu) is Gutgsell Endowed Professor of Communications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Five years after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–09 began there is still no sign of a full recovery of the world economy. Consequently, concern has increasingly shifted from financial crisis and recession to slow growth or stagnation, causing some to dub the current era the Great Stagnation.1 Stagnation and financial crisis are now seen as feeding into one another. Thus IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde declared in a speech in China on November 9, 2011, in which she called for the rebalancing of the Chinese economy:

The global economy has entered a dangerous and uncertain phase. Adverse feedback loops between the real economy and the financial sector have become prominent. And unemployment in the advanced economies remains unacceptably high. If we do not act, and act together, we could enter a downward spiral of uncertainty, financial instability, and a collapse in global demand. Ultimately, we could face a lost decade of low growth and high unemployment.2

To be sure, a few emerging economies have seemingly bucked the general trend, continuing to grow rapidly—most notably China, now the world’s second largest economy after the United States. Yet, as Lagarde warned her Chinese listeners, “Asia is not immune” to the general economic slowdown, “emerging Asia is also vulnerable to developments in the financial sector.” So sharp were the IMF’s warnings, dovetailing with widespread fears of a sharp Chinese economic slowdown, that Lagarde in late November was forced to reassure world business, declaring that stagnation was probably not imminent in China (the Bloomberg.com headline ran: “IMF Sees Chinese Economy Avoiding Stagnation.”)3

Nevertheless, concerns regarding the future of the Chinese economy are now widespread. Few informed economic observers believe that the current Chinese growth trend is sustainable; indeed, many believe that if China does not sharply alter course, it is headed toward a severe crisis. Stephen Roach, non-executive chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, argues that China’s export-led economy has recently experienced two warning shots: first the decline beginning in the United States following the Great Financial Crisis, and now the continuing problems in Europe. “China’s two largest export markets are in serious trouble and can no longer be counted on as reliable, sustainable sources of external demand.”4

In order to avoid looming disaster, the current economic consensus suggests that the Chinese economy needs to rebalance its shares of net exports, investment, and consumption in GDP—moving away from an economy that is dangerously over-reliant on investment and exports, characterized by an extreme deficiency in consumer demand, and increasingly showing signs of a real estate/financial bubble. But the very idea of such a fundamental rebalancing—on the gigantic scale required—raises the question of contradictions that lie at the center of the whole low-wage accumulation model that has come to characterize contemporary Chinese capitalism, along with its roots in the current urban-rural divide.

Giving life to these abstract realities is the burgeoning public protest in China, now consisting of literally hundreds of thousands of mass incidents a year—threatening to halt or even overturn the entire extreme “market-reform” model.5 China’s reliance on its “floating population” of low-wage internal migrants for most export manufacture is a source of deep fissures in an increasingly polarized society. And connected to these economic and social contradictions—that include huge amounts of land seized from farmers—is a widening ecological rift in China, underscoring the unsustainability of the current path of development.

Nor are China’s contradictions simply internal. The complex system of global supply chains that has made China the world’s factory has also made China increasingly dependent on foreign capital and foreign markets, while making these markets vulnerable to any disruption in the Chinese economy. If a severe Chinese crisis were to occur it would open up an enormous chasm in the capitalist system as a whole. As the New York Times noted in May 2011, “The timing for when China’s growth model will run out of steam is probably the most critical question facing the world economy.”6 More important than the actual timing, however, are the nature and repercussions of such a slowdown.

Capitalist Contradictions with Chinese Characteristics

For many the idea that the Chinese economy is rife with contradictions may come as something as a surprise since the hype on Chinese growth has expanded more rapidly than the Chinese economy itself. As the Wall Street Journal sardonically queried in July 2011, “When exactly will China take over the world? The moment of truth seems to be coming closer by the minute. China will become the largest economy by 2050, according to HSBC. No, its 2040, say analysts at Deutsche Bank. Try 2030, the World Bank tells us. Goldman Sachs points to 2020 as the year of reckoning, and the IMF declared several weeks ago that China’s economy will push past America’s in 2016.” Not to be outdone, Harvard historian Niall Ferguson declared in his 2011 book, Civilization: The West and the Rest, that “if present rates persist China’s economy could surpass America’s in 2014 in terms of domestic purchasing power.”7

This prospect is generally viewed with unease in the old centers of world power. But at the same time the new China trade is an enormous source of profitability for the Triad of the United States, Europe, and Japan. The latest round of rapid growth that has enhanced China’s global role was an essential component of the recovery of global financialized capitalism from the severe crisis of 2007–09, and is counted on in the future.

There are clearly some who fantasize, in today’s desperate conditions, that China can carry the world economy on its back and keep the developed nations from what appears to be a generation of stagnation and intense political struggles over austerity politics.8 The hope here undoubtedly is that China could provide capitalism with a few decades of adequate growth and buy time for the system, similar to what the U.S.-led debt and financial expansion did over the past thirty years. But such an “alignment of the stars” for today’s world capitalist economy, based on the continuation of China’s meteoric growth, is highly unlikely.

“Let’s not get carried away,” the Wall Street Journal cautions us. “There’s a good deal of turmoil simmering beneath the surface of China’s miracle.” The contradictions it points to include mass protests (rising to as many as 280,000 in 2010), overinvestment, idle capacity, weak consumption, financial bubbles, higher prices for raw materials, rising food prices, increasing wages, long-term decline in labor surpluses, and massive environmental destruction. It concludes, “If nothing else, the colossal challenges that lie ahead for China provide an abundance of good reasons to doubt long-term projections of the country’s economic supremacy and global dominance.” The immediate future of China is therefore uncertain, throwing added uncertainty on the entire global economy. As we shall see, not only might China not bail out global capitalism at present, an argument can be made that it constitutes the single weakest link for the global capitalist chain.9

At question is the extraordinary rate of Chinese expansion, especially when compared with the economies of the Triad. The great divergence in growth rates between China and the Triad can be seen in Chart 1 (below), showing ten-year moving averages of annual real GDP growth for the United States, the European Union, and Japan, from 1970 to 2010. While the rich economies of the United States, Western Europe, and Japan have been increasingly prone to stagnation—overcoming this in 1980–2006 only by means of a series of financial bubbles—China’s economy over the same period (beginning in the Mao era) has continually soared. China managed to come out of the Great Financial Crisis period largely unaffected with a double-digit rate of growth, at the same time that what The Economist has dubbed “the moribund rich world” was laboring to achieve any positive growth at all.10

Chart 1. Change in Real GDP, 1970–2010 (Ten-Year Moving Average of Percent Change From Previous Year)

Chart 1. Change in Real GDP, 1970–2010 (Ten-Year Moving Average of Percent Change From Previous Year)

Sources: WDI database for China, Japan, and the European Union (

) and St. Louis Federal Reserve Database (FRED) for the United States (

).

To give a sense of the difference that the divergence in growth rates shown in Chart 1 makes with respect to exponential growth, an economy growing at a rate of 10 percent will double in size every seven years or so, while an economy growing at 2 percent will take thirty-six years to double in size, and an economy growing at 1 percent will take seventy-two years.11

The economic slowdown in the developed, capital-rich economies is long-standing, associated with deepening problems of surplus capital absorption or overaccumulation. As the New York Times states, “Mature countries like the United States and Germany are lucky to grow about 3 percent annually”—indeed, today we might say lucky to grow at 2 percent. Japan’s growth rate has averaged less than 1 percent over the period 1992 to 2010. As Lagarde noted in a speech in September 2011, according to the latest IMF projections, “the advanced economies will only manage an anemic 1 1/2-2 percent” growth rate over the years 2011–12. China, in contrast, has been growing at 10 percent.12

The problems of the mature economies are complicated today by two further features: (1) the heavy reliance on financialization to lift the economy out of stagnation, but with the consequence that the financial bubbles eventually burst, and (2) the shift towards the corporate outsourcing of production to the global South. World economic growth in recent decades has gravitated to a handful of emerging economies of the periphery; even as the lion’s share of the profits derived from global production are concentrated within the capitalist core, where they worsen problems of maturity and stagnation in the capital-rich economies.13

As the structural crisis within the center of the capitalist world economy has deepened, the hope has been raised by some that China will serve to counterbalance the tendency toward stagnation at the global level. However, even as this hope has been raised it has been quickly dashed—as it has become increasingly apparent that cumulative contradictions are closing in on China’s current model, producing growing panic within world business.

Ironically, today’s fears regarding the Chinese economy stem in part from the way China engineered its way out of the global slump brought on by the Great Financial Crisis—a feat that was regarded initially by some as conclusive proof that China had “decoupled” itself from the West’s fate and represented an unstoppable growth machine. Faced with the world crisis and declining foreign trade, the Chinese government introduced a massive $585 billion stimulus plan in November 2008, and urged state banks aggressively to make new loans. Local governments in particular ran up huge debts associated with urban expansion and real estate speculation. As a result, the Chinese economy rebounded almost instantly from the crisis (in a V-shaped turnaround). The growth rate was 7.1 percent in the first half of 2009 with state-directed investments estimated as accounting for 6.2 percentage points of that growth.14 The means of accomplishing this was an extraordinary increase in fixed investment, which served to fill the gap left by falling exports.

This can be seen in Table 1, which shows the percent contribution to China’s GDP of consumption, investment, government, and trade (net exports). The sharp increase in investment as a share of GDP, which rose 7 percentage points between 2007–10, mirrored the sharp decrease in the share of both trade and consumption over the same period, which dropped 5 and 2 percentage points, respectively. Meanwhile, the share of government spending in GDP remained steady. Investment alone now constitutes 46 percent of GDP, while investment plus trade equals 52 percent.

Table 1. Percent Contribution to China’s GDP, 2002–2010

A

B

C

D

B+D

Consumption

Investment

Government

Trade

Investment

+ Trade

2002

44.0

36.2

15.6

4.2

40.4

2003

42.2

39.1

14.7

4.0

43.1

2004

40.6

40.5

13.9

5.1

45.6

2005

38.8

39.7

14.1

7.4

47.1

2006

36.9

39.6

13.7

9.7

49.3

2007

36.0

39.1

13.5

11.4

50.5

2008

35.1

40.7

13.3

10.9

51.6

2009

35.0

45.2

12.8

7.0

52.2

2010

33.8

46.2

13.6

6.4

52.6

Sources: Pettis, “Lower Interest Rates, Higher Savings?”

, October 16, 2011; China Statistical Yearbook.

As Michael Pettis, a professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and a specialist in Chinese financial markets, explained, the sharp drop in the trade surplus in the crisis might “have forced GDP growth rates to nearly zero.” However, “the sudden and violent expansion in investment” served as “the counterbalance to keep growth rates high.” Of course behind the dramatic ascent of the investment share of GDP, rising 10 percentage points during the years 2002–10, lay the no less dramatic descent of the consumption share, which dropped 10 perentage points over the same period, from 44 percent to 34 percent, the smallest share of any large economy.15

With investment spending running at close to 50 percent in this period the Chinese economy is facing widening overaccumulation problems. For New York University economist Nouriel Roubini:

The problem, of course, is that no country can be productive enough to reinvest 50% of GDP in new capital stock without eventually facing immense overcapacity and a staggering non-performing loan problem. China is rife with overinvestment in physical capital, infrastructure, and property. To a visitor, this is evident in sleek but empty airports and bullet trains (which will reduce the need for the 45 planned airports), highways to nowhere, thousands of colossal new central and provincial government buildings, ghost towns, and brand-new aluminum smelters kept closed to prevent global prices from plunging.

Commercial and high-end residential investment has been excessive, automobile capacity has outstripped even the recent surge in sales, and overcapacity in steel, cement, and other manufacturing sectors is increasing further…. Overcapacity will lead inevitably to serious deflationary pressures, starting with the manufacturing and real-estate sectors.

Eventually, most likely after 2013, China will suffer a hard landing. All historical episodes of excessive investment—including East Asia in the 1990’s—have ended with a financial crisis and/or a long period of slow growth.16

Overinvestment has been accompanied by increasing financial frailty raising the question of a “China Bubble.” The government’s fixed investment stimulus worked in part through encouragement of massive state bank lending and a local borrowing binge, resulting in further speculative boom centered primarily on urban real estate. China’s urban expansion currently consumes half of the world’s steel and concrete production as well as much of its heavy construction equipment. Construction accounts for about 13 percent of China’s GDP.

Although insisting that the bursting of China’s “big red bubble” still is “ahead of us,” Forbes magazine cautioned its readers in 2011 that “China’s real estate bubble is multiplying like a contagious disease,” asking: “China’s housing market: when will it pop, and how loud of an explosion will it make when it goes boom?” But for all of that, Forbes added reassuringly that “China’s property bubble is different,” since it is all under the watchful eyes of state banks that operate like extensions of government departments.

This notion of a visionary and wise Chinese state that can demolish any obstacles put before the economy on its current path, is the corollary of the notion that the Chinese economy as it now exists will grow at double-digit annual rates far into the future. It is an illusion—or delusion. The Chinese model of integration into global capitalism contains contradictions that will obstruct its extension.

This is certainly true in finance. While Forbes is hopeful, the Financial Times reports something quite different. State banks, supposedly at the center of the financial system, have been hemorrhaging in the last few years due to the loss of bank deposits to an unregulated shadow banking system that now supplies more credit to the economy than the formal banking institutions do. Indicative of a shift toward Ponzi finance, the most profitable activity of state banks is now loaning to the shadow banking system. A serious real estate downturn began in August 2011 when China’s top ten property developers reported that they had unsold inventories worth $50 billion, an increase of 46 percent from the previous year. Property developments are highly leveraged and developers have become increasingly dependent on underground (shadow) lenders, who are demanding their money. As a result, prices on new apartments have been slashed by 25 percent or more, reducing the value of existing apartments. China in late 2011 was experiencing a significant property price downturn, with sharp drops in home prices, which had risen by 70 percent since 2000.

Mizuho Securities Asia bank analyst Jim Antos, a close observer of the sector, estimated in July 2011 that bank lending doubled between December 2007 and May 2011, and although the rate of increase has declined over the last year, it remains far higher than the growth in GDP. As a result, Antos calculates that bank loans stood at $6,500 per capita in 2010 compared to GDP per capita of $4,400, and that the disproportion continues to increase, a situation he terms “unsustainable.” In addition there are unknown amounts of off-balance-sheet loans, and the current reporting of non-performing loans at 1 percent of total loans only serves to guarantee a sharp increase in this rate in the near future by 100 percent and up. Antos and other observers have noted that the banks’ capitalization was inadequate even prior to the break in real estate prices. Despite the vast financial resources that the Chinese government has in its role as lender of last resort, a sharp decline in real estate prices and in construction, and therefore in GDP, would produce a full-blown crisis of market confidence in a situation marked by great uncertainty and fear.17

Already in 2007 Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao declared that China’s economic model was “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and ultimately unsustainable.” Five years later this is now more obvious than ever. The most intractable problem, the root cause of instability, is the low and declining share of GDP devoted to household consumption, which has dropped around 11 percentage points in a decade, from 45.3 percent of GDP in 2001 to 33.8 percent in 2010. All the calls for rebalancing thus boil down to the need for a massive increase in the share of consumption in the economy.

Such rebalancing has been a major goal of the Chinese government since 2005, and there is no shortage of proposals on how to accomplish it. But they all founder in the face of the underlying reality. As Michael Pettis states: “Low consumption levels are not an accidental coincidence. They are fundamental to the growth model.” First among the relevant factors is the (super)exploitation of workers in the new export sectors, where wages grow slowly while productivity with advanced technology grows rapidly. The rise in wages necessary to yield an increase in consumption as a share of GDP would drive the large foreign-owned assembly plants to countries with lower wages. And the surrounding penumbra of small- and middle-scale plants run by Chinese capitalists would also begin to disappear, squeezed by tightening credit and already increasingly prone to embezzlement and flight.18

The declining share of consumption in GDP is sometimes attributed to China’s high savings rate, largely associated with the attempts by people to put aside funds to safeguard their future due to the lack of national safety net. Between 1993 and 2008 more than 60 million state sector jobs were lost, the majority through layoffs due to the restructuring of state-owned enterprises beginning in the 1990s. This represented a smashing of the “iron rice bowl” or the danwei system of work-unit socialism that had provided guarantees to state-enterprise workers.19 Social provision in such areas as unemployment compensation, social insurance, pensions, health care, and education have been sharply reduced. As Minxin Pei, senior associate in the China Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has written:

Official data indicate that the government’s relative share of health-care and education spending began to decline in the 1990s. In 1986, for example, the state paid close to 39 percent of all-health care expenditures…. By 2005, the state’s share of health-care spending fell to 18 percent…. Unable to pay for health care, about half of the people who are sick choose not to see a doctor, based on a survey conducted by the Ministry of Health in 2003. The same shift has occurred in education spending. In 1991, the government paid 84.5 percent of total education spending. In 2004, it paid only 61.7 percent…. In 1980, almost 25 percent of the middle-school graduates in the countryside went on to high school. In 2003, only 9 percent did. In the cities, the percentage of middle-school graduates who enrolled in high school fell from 86 to 56 percent in the same period.20

The growing insecurity arising from such conditions has compelled higher savings on the part of the relatively small proportion of the population in a position to save.

However, the more fundamental cause for rapidly weakening consumption is growing inequality, marked by a falling wage share and declining incomes in a majority of households. As The Economist magazine put it in October 2007, “The decline in the ratio of consumption to GDP does not reflect increased saving; instead, it is largely explained by a sharp drop in the share of national income going to households (in the form of wages, government transfers and investment income). Most dramatic has been the fall in the share of wages in GDP. The World Bank estimates that this has dropped from 53 percent in 1998 to 41 percent in 2005.”21

The core contradiction thus lies in the extreme form of exploitation that characterizes China’s current model of class-based production, and the enormous growth of inequality in what was during the Mao period one of the most egalitarian societies. Officially the top 10 percent of urban Chinese today receive about twenty-three times as much as the bottom 10 percent. But if undisclosed income is included (which may be as much as $1.4 trillion dollars annually), the top 10 percent of income recipients may be receiving sixty-five times as much as the bottom 10 percent.22 According to the Asian Development Bank, China is the second most unequal country in East Asia (of twenty-two countries studied), next to Nepal. A Boston Consulting Group study found that China had 250,000 U.S. dollar millionaire households in 2005 (excluding the value of primary residence), who together held 70 percent of the country’s entire wealth. China is a society that still remains largely rural, with rural incomes less than one-third those in cities. The majority of workers in export manufacturing are internal migrants still tied to the rural areas, who are paid wages well below those of workers based in the cities.

more at