You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

China's Space Program Thread II

- Thread starter Blitzo

- Start date

The pace of public progress Landspace is making is impressive, as well as Space Pioneer, iSpace and a few other private spaceflight companies.

The relative speed of the likes of CASC, CALT by comparison is certainly more traditional, and I do wonder whether they are looking at a way to reorient their priorities given they seem to recognize how the likes of SpaceX have achieved successes. It's not like the state companies lack expertise or resourcing if the government is committed to it.

Rather I feel like the lack of focus and having too many parallel project being cooked, and an insufficient appetite for risk (or unwillingness to accept a "test and blow up" mentality) is hindering them somewhat.

It should be apparent within the last year or two that of the major projects being worked on, the CZ-10 family and CZ-9 family are the most important and future proof and relevant capabilities, and I've felt for a while that concentrating resources on only those two platforms (maybe one other based on industry/strategic priority) should really be the order of the day.

Maybe CASC is an inherently slow organization, however I suspect that a major reason why CASC seems slow might be that they have been bleeding personnel to all the new Chinese launch companies. This has likely caused a lot of disruption and slowdowns of work at CASC. I believe high-profile examples are Kang Yonglai and Zhang Xiaoping (1). Both of these were managers at CASC, and as soon as they started working for Landspace they probably began trying to poach all the best employees from their former workplace. China is also seeing major expansion in other sectors that partially or fully compete for the same labor, such as space payloads, missiles, aircraft and drones. This includes, as you say, competition for labor internally within CASC too. China's aerospace labor pool is expanding, however CASC's launch divisions are at the same time also facing greater competition for labor.

I don't think the value of CZ-10A should be overemphasized. It seems like an inefficient kludge solution, not suitable for large-scale use. The stated payload mass fraction is not very impressive. The figures might be based on a very conservative "minimum" calculation, however even that should be better. An YF-100-based engine ought to have the performance of a reasonably mature engine, so an underoptimized engine doesn't seem like a likely explanation. It benefits from ORSC too. I think the reason could be that the CZ-10A design is constrained by design choices made for other rockets. It is to use engines and tank diameter similar to rockets that already exist. It was also designed to have a high degree of commonality with the CZ-10, and I suspect CZ-10 requirements took priority on common elements because a lunar mission gravely needs every kilogram to TLI that it can muster.

I don't think CASC needs to hurry with the CZ-10A. There are numerous other Chinese companies chasing Falcon 9 clones. China's launch industry does not depend on CASC also fielding one. I think the main importance of CZ-10A is that CASC needs institutional experience with recovery and reuse of boosters and engines from realistic orbital missions before freezing the CZ-9 design. The CZ-10A is very suitable for that purpose, because it recycles a lot of previous work, and so the initial fixed costs should be low. A first launch of CZ-10A even as late as 2028 should still work fine for that purpose. I would not worry that it will delay China's adoption of reusable rockets, because CASC's major contribution to that area won't come until the CZ-9, and YF-215 development is the main delaying factor for that.

What I think CASC (and also CASIC) need to focus on doing, is what other companies aren't doing:

(a) Provide a highly predictable, schedule-safe and reliable baseline capacity in China's launch industry, that the government can count on for strategic imperatives. The CZ-2-8 are very well suited to this, due to being flown designs, with production lines already running or well into the process of ramping up.

(b) Research and work on launch-related technology that few or no other Chinese companies are, due to it being financially risky, excessively ambitious, or optimized for non-commercial needs, e.g. Tengyun, Sino-STS, air-launch, YF-215, wartime emergency launch systems, wire-catched boosters, new manufacturing techniques, etc.

(c) Help fledgling Chinese launch companies, e.g. by providing test facilities, equipment and components, and yes, by bleeding personnel and partially cannibalizing itself. While it slows down CASC in the near term, a restructuring of the industry is good in the long term.

CZ-5-8 might not be hopelessly obsolete either. As was mentioned in this thread, USSF's Ron Lerch made public an estimate that the marginal cost of launch is $3000/kg for CZ-5 (I assume he meant CZ-5B to ~400km LEO.) If true, is a very reasonable price to pay for launches that can be had soon and with very high schedule predictability. So I can certainly understand if CASC maintains full steam ahead for CZ-5-8, even if it is at the expense of CZ-10A.

Even if I am wrong and the CZ-10A will become the central pillar of Chinese spaceflight, work today on CZ-5-8 is not wasted, assuming YF-100 engine production lines are easy to convert to YF-100K/M production.

(1)

Post divided into two because it exceeded the character limit

This makes sense when you are launching stacks of small payloads, like Starlink. Then constraints and optimal points of payload volume and mass do not matter as much, because you can just launch a smaller stack.I agree that they are working wayyy too many rockets. Sure it make sense for there to be almost a dozen long march rockets for every situation and payload capacity needed, but focusing solely on 1 or 2 workhorse rockets and improving them to the peak of what current technology allows seems to have it's advantages.

It also makes sense to have fewer rocket models if they are reusable in the style of Falcon 9. It allows for several "optimal" payload masses. You have the option of expending the booster, landing it downrange, or returning to launch site, all with different maximum payload masses. Indeed, this is the stated rationale of the Maia rocket. They do not expect to save any money with reuse in terms of euros per kilogram to orbit (1). With a Falcon Heavy style tricore rocket, you have even more booster recovery options and thus even more optimal payload masses.

I'm don't think China having a dozen rocket variants matters that much. It matters for development and testing, however it should not matter much for production and operation, because the production lines have a great deal of commonality, granting virtually all the benefits of economies of scale. To the extent having a dozen variants increases costs, those are sunk costs that have been paid for by now anyway.

In case you meant a rocket that is at the global state of the art: rockets at the peak of current technology have development times of ~10 years, even in America which has the greatest pool of experience and expertise. Look at Raptor and BE-4. Aiming for the state of the art involves a lot of schedule uncertainty. And by the time development finishes, it might no longer be state of the art. Just look at New Glenn. Or look at China's kerolox rockets, which would have been considered state of the art if the year was still 2012.

Doesn't help that they still refuse to let go of the 30 year old hypergolic long march rockets that still make up like 50% of all Chinese launches. That's a lot of manpower, logistics and man hours spent on a rocket and fuel that's obsolete 30 years ago.

I don't think all resources are necessarily completely fungible between hypergolic and kerolox rockets. For example, if the Xichang launch complex is shut down, many employees will probably quit their jobs rather than move all the way to Wenchang. I do not know how CASC facilities are distributed regarding the value chains for hypergolic versus kerolox rockets, however it might be similar problems there, with factories in some cities dedicated to components for one or the other. It might not be considered worth it to fully convert the entire hypergolic value chain to kerolox, because technology is already running away from the YF-100 engine and it might be more economical to just convert directly to the methalox/YF-215 value chain in a few years. Or maybe they are converting everything to kerolox, it just hasn't finished yet.

CASC seems perfectly willing to throw itself at risky technology. For example, they have been working on a HTVL spaceplane, which as I understand it is conceptually similar to either XS-1 or the original Space Shuttle design that was never implemented (2). Another example is the wire-catched booster of CZ-10A. Indeed, out of all Chinese launch companies, CASC and CASIC seem to be ones with the most willingness to take on risky projects. Other Chinese launch companies prefer to follow the already trodden path of SpaceX. Which is understandable. Project failures are a potentially existential matter for them, and are not for CASC or CASIC. However, just because CASC can take on risky projects, doesn't mean CASC can also risk the "guaranteed baseline" of launch.proven technology, new technology introduces risk and we can't have risk, we worked with this technology for the last 20 years and the head of the agency can't handle change

I will give them some credit, at least they shifted really fast by pivoting to reusable rockets since 2016 instead of sticking their heads into the sand. If you look at other space agencies like ESA, JAXA, ISRO, Roscosmos they basically still considering reusable rockets and are still in the very early R&D phase while CASC is already testing hardware. Meanwhile NASA has completely given up and will probably stick to the SLS until SpaceX finally kills it. Europe, Japan, India and Russia also doesn't really have a competitive private space sector at all.

I do not think it is a case of Europe, Japan, India and Russia sticking their heads in the sand. Rather, it is that there is not enough demand on their home markets to have the economies of scale to justify reusability. Neither do they think they can compete on the international market against current and future industry leaders in America, who have first mover advantage, and also inherently benefit from the much larger economies of scale of America's own home market. So why would they waste money trying. Outside the US, it is only for Chinese companies that reusability is immediately meaningful.

In 2016, Ariane 6 was only given guarantees of 5 launches per year. So it is not surprising that they planned for a launch cadence of just 11 per year and made design and investment decisions accordingly. ArianeGroup head Charmeau said as much; an annual launch cadence of 30 or more would have been needed to justify reusability (3). Europe's launch capability is really France's; they are the only ones who seem to care. Germany's SARah, Italy's CSG-2, ESA's Euclid and EU's Galileo immediately ran to SpaceX when European options turned out to be imperfect, delayed or overbooked. Which I think says all one needs to know about their level of belief in the need of an independent and robust European launch capability. Besides, Italy would probably have hated any Ariane 6 design that made the Avio SRBs optional.

Russia lost a lot of international launch business after 2022. They probably have an excess in launch capacity, and are mainly constrained by their own capacity to produce useful payloads. Thus it makes sense that Roscosmos is not investing much resources into the Soyuz-7 project at this time and that it is being delayed to 2028-2030.

H-IIA flies a few times a year. Does it make sense for the successor H-3 to be reusable? Besides, Japan needs to keep an SRB industry alive in order to keep ICBMs within easy each.

NASA was instrumental in funding Falcon 9 development and uses it frequently today. Just because NASA's contracts with SpaceX have the structure of NASA buying a service rather than buying vehicle components, does not mean NASA doesn't use Falcon 9. However, NASA is politically mandated to continue with SLS in parallel.

(1)

(2)

(3)

Post split again because of character limit

I think there might be several good reasons that combine to justify there being many solid propellant rocket projects in China.The state owned spinoff companies like CAS space also have the same issue, do we really need a dozen versions of the same small lift solid fueled rocket?

Low barriers

Some launch companies that developed a solid propellant rocket first likely did so because they wanted to launch something to prove themselves to investors as fast as possible, and in the early days of Chinese commercial launch, rocket engines using solid propellant were the only ones available for purchase off-the-shelf.

Commonality of components

The number of distinct solid propellant launch systems might give the impression of more duplication than there actually is. A lot of components and their production lines are probably common between various rockets or with PLA missiles, and thus there is not that much waste by duplication. I believe for example that CASC's SD-3 and CAS Space's LJ-1 use the same 2.65m SP70 rocket motors from CASC (1). I think Galactic Energy's Ceres-1 and iSpace's SQX-1 have the same 1.4m diameter as KZ-1A/JL-1/DF-21/DF-26, so they might be related to either.

Idle production lines and economies of scale with missile production

Suppose a single, indivisible production line for a certain type of rocket motor is capable of producing 30 motors per year. Suppose the PLA only wants 20 motors per year. Does it not make sense to still build the extra 10 and sell them to launch companies at marginal production cost?

PLA demand for rocket motors of certain types might vary over time. For example, demand might peak as a new ICBM silo field is built. Yet the annual capacity of the equipment in the factory that produces that particular rocket motor remains constant, and you do not want to fire employees during demand downturns because it would be hard to get them to come back when PLA demand increases again. Does it not make sense to keep the production line running anyway in the meantime, and sell excess motors cheaply to launch companies?

Expiring or obsolete missiles

As I understand it, common types of solid propellant rocket motors tend to chemically degrade over time, depending on temperature and other storage conditions. One use of missiles that are nearing their shelf life is to launch them in exercises, however such exercises have diminishing returns, and eventually a higher launch exercise frequency becomes almost pointless. Some missiles become technically obsolete and there is no point in either keeping them or exercising with them. If a lot of missiles expire at the same time, or if they reach obsolescence, it might make sense to dismantle missiles and sell the rocket motors to launch companies.

Schedule flexibility

If you are a payload company that is developing and building a prototype payload, you might not know ahead of time when the payload will be ready, however you want to test it immediately once it is ready. Because the sooner you can test, the faster you can iterate, and the faster you can complete the development cycle. This saves money on engineer salaries and capital costs, and brings the product to market sooner. Therefore you might be willing to pay extra to have a rocket that will wait for you, either by sharing a rocket with others that pay less for being willing to wait, or by buying a dedicated rocket.

Launch sites for liquid propellant rockets are expensive. Launch sites for solid propellant rockets are cheap. If you are a launch company that wants to offer maximum schedule flexibility, this means your launch sites will have to be underutilized, and so the cost of launch sites will weight more heavily in your cost calculation. Experimental payloads can vary a great deal in shape and mass, justifying a range of solid rockets.

Wartime resilience

In case of war, launch sites might be destroyed. The military will value launch systems that have redundancy and survivability. Relocatable launch infrastructure is the most survivable. This is far easier to build for solid propellant rockets. I think the Kuaizhou series, Jielong series, and CZ-11 are designed with this in mind.

Even if a solid propellant rocket is mainly intended for wartime launch, it still needs to be launched in peacetime. Firstly, you need many launches to verify the reliability of the rocket. Secondly, you need to launch stored rockets as they are about to expire. Thirdly, you need to maintain and train the launch staff, and if you are paying their salaries, you might as well have them launch stuff.

Static launch infrastructure for solid propellant rockets is also quite resilient, in the sense that it is relatively cheap to build lots of, and relatively easy to repair.

Floating launch pads

Jiuquan and Wenchang might geographically be great places to launch rockets from, however some skilled aerospace workers might not want to live there. Especially not Jiuquan. Floating launch sites make it possible to base your launch operations along the mainland coast where it might be easier to recruit skilled staff without having to pay premium salaries. You can also choose to build (or convert) a floating launch site almost anywhere along the coast, wherever the relevant construction labor is the cheapest. Floating launch sites for solid propellant rocket are far easier to build and operate than for liquid propellant rockets.

(1)

The CZ-10 is supremely important. It will enable replacing the older generation of rockets like the Long March 7 and 5 with a much cheaper to manufacture rocket. Which will become even cheaper once they make it reusable. It also does this with minimal expense to develop the requisite production facilities since it reuses existing infrastructure.

by78

General

The private launch provider DeepBlue Aerospace has successfully completed China's first non-pyrotechnical fairing separation test. The fairing design is destined for the Nebula-1 reusable launch vehicle.

DeepBlue Aerospace has successfully completed extension tests of the landing leg design for its Nebula-1 reusable launch vehicle.

Last edited:

by78

General

The Long March 5 rocket launched last Friday featured propellant tanks fabricated using , which is a first for China. The technique is crucial for the development of future large diameter rockets because it doesn't need a required by traditional friction stir welding techniques.

Last edited:

Tianwen-4 is planned to be launched in September 2029..

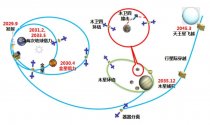

The Tianwen-4 mission consists of two detectors and will use the slingshot effect of Venus and Earth's gravity to fly to Jupiter.

Venus will borrow the force in April 2030, and the Earth will borrow the force in 2031 and 2033. It will capture Jupiter in December 2035 and fly by Uranus in March 2045. The Tianwen-4 main detector will enter the Jupiter galaxy for a detection mission and enter the orbit of Callisto. The smaller detector will separate from the main detector before it enters the orbit of Jupiter and fly over Uranus.

The Tianwen-4 mission consists of two detectors and will use the slingshot effect of Venus and Earth's gravity to fly to Jupiter.

Venus will borrow the force in April 2030, and the Earth will borrow the force in 2031 and 2033. It will capture Jupiter in December 2035 and fly by Uranus in March 2045. The Tianwen-4 main detector will enter the Jupiter galaxy for a detection mission and enter the orbit of Callisto. The smaller detector will separate from the main detector before it enters the orbit of Jupiter and fly over Uranus.