Adidas was one of the main brands smuggled into USSR during the peak years of, what Soviet citizens called "deficit" (shortage of consumer goods). It was a very visible brand for sporting events which were quite popular in USSR. That symbolic value added to its perception of quality, but outside of the quality and iconic status in sports, it was a rare commodity that had to be imported, which made it a status symbol.My great great question is why USSR athletic apparels were adidas? It was so difficult for USSR industry to produce such quality clothes or ADIDAS was paying the expences for the teams in return of subtle advertisment? LoL It utterly cultivated the Gopnik culture of Russia. The Russian rednecks

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Russia Economy Thread

- Thread starter NiuBiDaRen

- Start date

Very true about Perestroika. Really led to political divisions and sewed mistrust. Initiated racially charged politics as well and stoked division.The Soviet Union had a similar system to Chines Hukou, and yeah, it is a massive success to take millions of people out of the ruins of World War 2, and put them, their children, and their grand-children into much better housing. So yeah, I find your framing absurd. It absolutely a massive success to then improve apartment buildings and single family homes decade on decade, which is what happened.

Not everyone had the luxury of having an untouched hemisphere with a massive GI program to build millions of housing units for returning soldiers.

Which is an absurd take. You do realize the country was literally destroyed after World War 2? It was even worse, I am a descendant of Koryo-Saram, a Korean diaspora in Central Asia. My great-grandparents were transferred from the Russian Far East into Central Asia, modern day Uzbekistan. There was literally no housing. So yes, going from shacks into a relatively decent, if inadequate, single family home was an enormous upgrade.

By US standards most European living spaces are woefully inadequate, but I wouldn't consider European homes and apartments to be unlivable.

Perestroika was literally one of the reasons why USSR collapsed. Becaues he deregulated the economy at a bad time, and he also partially deregulated in a way that exacerbated shortages and promoted hoarding.

Gorbachev's mismanagement was certainly bad, but the Soviet economic capacity was certainly not some decrepit elephant unable to make high quality goods. The biggest issue was shortage caused by Gorbachev's mismanagement. Not an inherent stagnancy of the Soviet economy.

The issue with central planning isn't the inability to produce competitive goods. Soviets have made plenty of world-class products in their history, inclduing the 80s. This was not a "stagnant" ot "backwards" society. The issue with central planning is inefficient allocation of resources.

But that's not even why the USSR collapsed anyway.

Perestroika actually decreased the purchasing power of the average Soviet citizen. The adoption of various appliances, availability of clothing, higher quality food, housing stock, etc all increased with time. Perestroika was catastrophic becuase it nearly reversed that trend completely.

Certainly, there were periods that were better and periods that were worse. The reason for Perestroika in the first place was the slowing of economic growth, but nonetheless there was growth and a general improvement to people's lives. By contrast, Perestroika was almost entirely a negative experience for people who lived through that time.

The minor improvements in avaialbility of some goods and services are entirely offset by the huge negative consequences of empty store shelves, which were a result of Perestroika, and not a sudden collapse of Soviet factories to make products.

Perestroika was almost the entire cause of USSR's economic collapse. Prior to 1986 the country wasn't collapsing. It wasn't even in crisis. The economic circumstances were a mere slow down of economic growth (which we don't even know since it's notoriously hard to measure). As late as 1985 motor vechiel production in USSR was still increasing, and it started decreasing as Gorbachev's reforms kicked in.

Anyway, the point is that USSR's economy was mostly "fine" and developing up until Gorbachev's reforms. Gorbachev's reforms hobbled what was otherwise a fairly productive economy, and the horrific politics killed all government legitimacy which resulted in the collapse.

It wasn't because the economy suddenly stopped working or was grossly uncompetitive with the rest of the world. That's just, basically, Western post-91 propaganda.

Gorbachev was a very weak leader. Cared more about optics in the west than actual improvement with the USSR. Didn't help thus Yeltsin was a bully. A lot of Soviet citizens fell for western propaganda as well. After the fall, they realized that they were tricked but it was too late.

manqiangrexue

Brigadier

IMF cannot reduce anyone's growth; they can only reduce or increase their guess of someone's growth. IMF estimates 0.6% Russian GDP growth this year, only 6X faster rather than 9x faster than the EU's 0.1%.GDP growth in Russia has been reduced by IMF again. 0.6 percent growth.

Russia energy week started with Saudi Prince Salman. The same Prince that few months ago Russia asked for investments in Far East. They already have Gas OPEC in addition to Oil OPEC. Russia has proposed Rare Earth alliance to them and i think Gold trading is very extensive all the way to Africa.

Russia gas consumption is upto 70% of US. it can surpass US consumption considering scale of single family home construction.

Russian Energy Week Forum kicks off with the participation of Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman

Saudi Arabia and Russia plan a joint business forum to enhance cooperation in 11 sectors.

Saudi Energy Minister from Moscow: Approximately 100 Russian companies and businessmen will participate alongside Saudi companies.

Secretary-General of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum: The golden age of natural gas is still ahead of us

From our point of view, we believe that the golden age of natural gas is still ahead of us," Hamel said at the Russian Energy Week in Moscow.

He added that approximately 200 million tons of LNG production capacity will be released worldwide by 2030, which represents both a challenge and an opportunity.

Global gas demand is expected to reach new record levels, with demand expected to grow by 1.6% in 2025 and 1.8% in 2026.

Global demand for gas is also expected to grow by 32% by 2050, with gas's share of the energy mix rising from 23% to 26%.

The Russian Energy Week forum, one of the most important international events in the energy sector, kicked off in Moscow today, Wednesday, with the participation of experts and officials from around the world, including Saudi Energy Minister Abdulaziz bin Salman.

The eighth edition of the international event will be held in the Russian capital from October 15 to 17, with representatives from 84 countries expected to participant

Russia gas consumption is upto 70% of US. it can surpass US consumption considering scale of single family home construction.

9.10.2025 | 12:35 GMT

Russia's Gazprom: Russia has no rival in gas reserves

10.10.2025

An industrial bridge between Moscow and Abu Dhabi: a development partnership on the grounds of Technopolis

Why are you claiming twice the emphasis on the destruction of the USSR in WWII?The Soviet Union had a similar system to Chines Hukou, and yeah, it is a massive success to take millions of people out of the ruins of World War 2, and put them, their children, and their grand-children into much better housing. So yeah, I find your framing absurd. It absolutely a massive success to then improve apartment buildings and single family homes decade on decade, which is what happened.

Not everyone had the luxury of having an untouched hemisphere with a massive GI program to build millions of housing units for returning soldiers.

Which is an absurd take. You do realize the country was literally destroyed after World War 2? It was even worse, I am a descendant of Koryo-Saram, a Korean diaspora in Central Asia. My great-grandparents were transferred from the Russian Far East into Central Asia, modern day Uzbekistan. There was literally no housing. So yes, going from shacks into a relatively decent, if inadequate, single family home was an enormous upgrade.

By US standards most European living spaces are woefully inadequate, but I wouldn't consider European homes and apartments to be unlivable.

Perestroika was literally one of the reasons why USSR collapsed. Becaues he deregulated the economy at a bad time, and he also partially deregulated in a way that exacerbated shortages and promoted hoarding.

Gorbachev's mismanagement was certainly bad, but the Soviet economic capacity was certainly not some decrepit elephant unable to make high quality goods. The biggest issue was shortage caused by Gorbachev's mismanagement. Not an inherent stagnancy of the Soviet economy.

The issue with central planning isn't the inability to produce competitive goods. Soviets have made plenty of world-class products in their history, inclduing the 80s. This was not a "stagnant" ot "backwards" society. The issue with central planning is inefficient allocation of resources.

But that's not even why the USSR collapsed anyway.

Perestroika actually decreased the purchasing power of the average Soviet citizen. The adoption of various appliances, availability of clothing, higher quality food, housing stock, etc all increased with time. Perestroika was catastrophic becuase it nearly reversed that trend completely.

Certainly, there were periods that were better and periods that were worse. The reason for Perestroika in the first place was the slowing of economic growth, but nonetheless there was growth and a general improvement to people's lives. By contrast, Perestroika was almost entirely a negative experience for people who lived through that time.

The minor improvements in avaialbility of some goods and services are entirely offset by the huge negative consequences of empty store shelves, which were a result of Perestroika, and not a sudden collapse of Soviet factories to make products.

Perestroika was almost the entire cause of USSR's economic collapse. Prior to 1986 the country wasn't collapsing. It wasn't even in crisis. The economic circumstances were a mere slow down of economic growth (which we don't even know since it's notoriously hard to measure). As late as 1985 motor vechiel production in USSR was still increasing, and it started decreasing as Gorbachev's reforms kicked in.

Anyway, the point is that USSR's economy was mostly "fine" and developing up until Gorbachev's reforms. Gorbachev's reforms hobbled what was otherwise a fairly productive economy, and the horrific politics killed all government legitimacy which resulted in the collapse.

It wasn't because the economy suddenly stopped working or was grossly uncompetitive with the rest of the world. That's just, basically, Western post-91 propaganda.

Do you know which countries also emerged from WWII destroyed?

Japan.

Basically almost all of Europe, and especially West Germany.

Do you know what they have in common? They all had a higher standard of living than the USSR.

I don't need to use the US (an untouched hemisphere) as a comparison with the Soviet economy to show how flawed the Soviet economic model was.

This is no excuse for the economic failure of the USSR.

The fact that you want to emphasize this is a glimpse into the absurdity of your defense of the Soviet economy, because even among comparisons of nations that were decimated in WWII, some countries emerged much more prosperous than the Soviets, which had a flawed economic model.

Another emphasis in your argument is perestroika. If the Soviet economy "was, for the most part, 'well' and developing," there was no reason to carry out perestroika in the first place.

Do you know why Gorbachev came to power?

Gorbachev came to power determined to promote several reforms to keep the Soviet Union afloat. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union found itself in a very delicate situation. The Soviet economy was in a severe crisis, with the country accumulating deficits due to high spending.

The Soviet economy was dependent on oil exports, and due to the drop in the price of this commodity on the international market, Soviet revenues began to plummet. Furthermore, Soviet agriculture suffered from low yields, forcing the government to export grain from foreign markets. The Soviet government also saw its economy bleed due to excessive spending on the Afghan War.

Politically, there was also strong popular dissatisfaction with the Soviet government, mainly due to the poor performance of the Soviet economy.

The fact that you say that until 1986, things were going well for the bloc economically is quite funny, because none of that is true. For example, using the example of motor vehicle production in the USSR increasing before Gorbachev and then decreasing with the implementation of Gorbachev's reforms is even funnier.

Do you know why this happened?

You yourself ended up answering in your comment. Here's your comment:

The problem with central planning is not the inability to produce competitive products.

I recommend you read the book "Icon" by Frederick Forsyth. In the book, he gives several descriptions of how the Soviet shadow economy worked. This economy was excellent for allocating scarce resources to which it had access, but manufacturing scarce resources was another matter. The book also shows how several Russian millionaires "magically" emerged after the end of the USSR: they were people who accumulated hard currency in the informal market by selling food or gasoline during the communist years. These people eventually became the Russian mafia. This is why today it is speculated that the black market always represented 40-50% of the entire Soviet economy.

It is well known that since the end of Brezhnev's rule, the Soviet economy had been stagnant. Andropov took office promising economic reforms to stem the economic crisis and the stagnation of the Soviet standard of living. There is no shortage of articles analyzing the descriptive scenario of the Soviet economy at the time:

Andropov died prematurely. He remained in office for months, promising to embark on a set of economic reforms. But like all failed Soviet planning, several Soviet economic experts believed his modernization program could be undermined by the entrenched central planning bureaucracy. This was the fate of the Brezhnev-Kosygin of 1965-70.

You need to consider the economic context.So, a 10% of GDP debt is the real cause for an economy to fail. Interesting, we live in a matrix indeed

The Soviet regime's preference for scarcity over inflation has its roots in the hyperinflationary history of the Soviet economy. By the mid-20th century, Soviet planners were well aware of the dangers of hyperinflation. With the end of the Tsarist regime and the conclusion of World War I, the new socialist regime took control of a country that was already bankrupt and highly dysfunctional. Hyperinflation soon followed. The Bolsheviks attempted to abolish money altogether, but this naturally failed, and a series of monetary reforms followed. By the late 1920s, however, the regime was engaging in widespread price control efforts, including the highly unusual tactic of rationing in peacetime. This limited price inflation for many goods and set the stage for the "suppressed inflation" that would become a pillar of the Soviet system for decades. Prices, however, began to rise rapidly in many areas, and World War II brought a new wave of price inflation, and prices soared. This was followed by another monetary reform—namely, the devaluation—of the Soviet ruble in 1947. Price control efforts were redoubled, and overall prices actually fell during the 1950s.

For much of the 1950s and early 1960s, the regime was perpetually concerned about price inflation. Indeed, Soviet ideology stipulated that inflation did not actually exist in the USSR. As Vasily Garbuzov, the Soviet Finance Minister, stated in 1960:

This is propaganda, of course, but in a sense, Garbuzov was right. A socialist state could indeed moderate the effects of monetary inflation on prices by reducing living standards and consumer choices whenever prices appeared to be rising.In the Soviet Union there is not and cannot be inflation; the possibility of inflation is completely excluded by the very system of the socialist planned economy. In our country, both wholesale and retail prices are set by the government, and thus the purchasing power of the ruble is deliberately controlled... The stability of the Soviet currency is guaranteed by the currency monopoly and the foreign trade monopoly, which is one of the most important advantages of the socialist economic system.

This was necessary because the money supply continually expanded as wages rose. In their 1985 study of the Soviet economy, Igor Birman and Roger Clarke wrote:

In an unencumbered economy, wages are closely tied to worker productivity, so wages would not rise disproportionately to the quantity of goods and services available in the economy. In a socialist economy, however, the price of labor—that is, wages—was arbitrarily set like all other prices. Wages under socialism are also paid by the public treasury and can be raised at the regime's convenience. This often meant wage increases because higher wages were politically popular. Rising wages potentially created the impression of prosperity, even when the economy was not actually more productive. Furthermore, as Birman and Clarke note:The reason for the excess money supply is that the state has consistently "overpaid" the population in the form of wages, pensions, benefits, etc., which exceed the production (plus net imports and minus net exports) of consumer goods at prevailing retail prices (set by the state). While there has indeed been a steady increase in retail prices (despite the stability of the official index), this has been far too insufficient to equalize the population's real effective demand with the available supply of goods. In other words, the state generates excessive purchasing power in the hands of the population.

Increasingly, after 1965, the Soviet money supply became disproportionate to the economy's productive capacity. In a relatively free economy, this would quickly lead to price inflation, but the Soviet regime had ways to shift the economic burden elsewhere.During the last two decades [i.e., from 1965 to 1985], the country pursued the “confidence trick” policy of trying to stimulate productivity through higher money wages, without increasing the supply of consumer goods nearly enough to translate the increase in money wages into higher real incomes.

Thus, prices were kept under control not through fiscal discipline but through price controls. This led to shortages because, if wages rose while product prices did not, demand quickly outstripped supply. Soviet citizens often found they had very little to spend their money on, resulting in the long lines and empty shelves we associate with the Soviet economy today.

Through this mechanism, the regime could continue to inject new money into the economy, but also prevent ordinary people from spending "too much" money and thus raising consumer prices. The downside, of course, was that living standards fell considerably, as historian Steven Efremov :

The result was essentially forced savings. Efremov continues:The price control system had deleterious effects on both Soviet consumers and the economy as a whole... Shortages of most foods led to inferior diets, and many consumer products routinely available in the West, such as telephones, cars, and modern washing machines, were surprisingly rare in the Soviet Union. Living conditions were less comfortable in many respects, with less living space per person, no central heating, no air conditioning, and often no sewer or hot water connections.

In some respects, this was beneficial for the regime, as these unspendable savings could also be used to purchase government debt. But this accumulated money—known as the "monetary surplus"—increased much faster than the production of goods and services, and Efremov concludes that "the money supply had grown far more than was necessary for regular circulation." This would come back to haunt the regime when the economy began to open up and consumers were finally able to spend their money, causing prices to soar.When consumers couldn't find anything they wanted to buy, many chose to save a portion of their income each year. This effect was cumulative over time, as unmet demand from one year was carried over to the next, and the population's savings continued to grow.

An additional method of reducing official inflation figures was subsidizing consumer goods. Retail price subsidies were introduced in the Soviet Union in 1965 as part of a major package of economic reforms. Soviet authorities then began implementing price subsidies on "basic foodstuffs such as meat, milk, bread, sausages, sugar, and butter." The goal was to keep prices stable. These subsidies survived subsequent economic reform efforts and became an increasingly large part of the economy in the early 1980s, with government spending increasing rapidly to put downward pressure on prices through subsidies.

None of this actually helped Soviet living standards.

To counter the effects of monetary expansion and falling living standards, the Soviet regime relentlessly tried to increase production to reduce the gap between monetary growth and productivity growth. However, due to the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism, Soviet central planning failed to coordinate goods and capital efficiently, and worker productivity stagnated.

Another result was an even greater decline in government revenue collection. Although taxes were levied and some revenue could be raised from imports, government monopolies—that is, state-owned enterprises—that controlled a variety of goods and services produced much of the income on which the regime depended. These enterprises could theoretically increase their revenues by increasing production, but production often stagnated as wages—that is, production costs—rose.

Government budgets, therefore, increased in tandem with falling revenues. Byung-Yeon Kim notes, for example, that "retail price subsidies…increased from 4 percent of government budget expenditures in 1965 to 20 percent in the late 1980s."

However, the availability of consumer goods certainly did not keep pace. Instead, consumers had few places to spend their money, and "the share of forced savings in total monetary savings increased from 9 percent in 1965 to 42 percent in 1989."

Judging by the prevalence of shortages, it's clear that the Soviet economy was in a state of stagnation in the late 1970s. Shortages worsened further. Kim concludes:You need to consider the economic context.

Wage increases continued to have little positive effect. Throughout the 1980s, Soviet state-owned enterprises raised wages in an attempt to create a "wealth effect" and placate dissatisfied workers. However, with few goods available to purchase, wage increases ceased to be a significant incentive to work harder. Birman and Clarke note that, after a while, wage increases "become ineffective—additional, unspendable money no longer provides an incentive to work harder or more productively." Worker productivity suffered. This problem only accelerated as the decade progressed, and, as Igor Filatochev and Roy Bradshaw note, "wages increased four times faster than labor productivity throughout 1989 and 1990."Consumer market conditions in the official retail network deteriorated rapidly between 1965 and 1978. This was most likely caused by the stability of consumer prices, amid rising consumer purchasing power. Although the rapid deterioration ceased between 1979 and 1983, it was not sufficient to restore equilibrium. Further deterioration in consumer market conditions occurred after 1984. In particular, consumer shortages intensified significantly in 1989, as household incomes increased much faster than the availability of consumer goods.

All this spending on wages and subsidies combined to create conditions under which government deficits increased, leading to even greater monetary expansion. Kim concludes:

Until the 1970s, there was a connection between revenues and expenditures to the point where deficits were manageable. As time passed, borrowing to cover deficits became increasingly costly for the regime, and printing money—in addition to the need for wages—became increasingly seen as a way out:Although the budget deficit was only officially recorded in 1985, many reliable Soviet and Western sources maintained that a sizable deficit existed long before the 1980s.

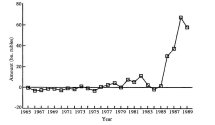

Money printing began well before the late 1980s, that is, from 1977 onward, and tended to increase throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s. Overall, the Soviet budget tended to destabilize the consumer market, at least after 1977, by putting money into circulation. In particular, a sharp increase in money printing in the late 1980s suggests that the Soviet economy was on the verge of collapse.

Byung-Yeon Kim, “Causes of Suppressed Inflation in the Soviet Consumer Market, 1965–1989:

Why are you claiming twice the emphasis on the destruction of the USSR in WWII?

Do you know which countries also emerged from WWII destroyed?

Japan.

Basically almost all of Europe, and especially West Germany.

Do you know what they have in common? They all had a higher standard of living than the USSR.

I don't need to use the US (an untouched hemisphere) as a comparison with the Soviet economy to show how flawed the Soviet economic model was.

This is no excuse for the economic failure of the USSR.

The fact that you want to emphasize this is a glimpse into the absurdity of your defense of the Soviet economy, because even among comparisons of nations that were decimated in WWII, some countries emerged much more prosperous than the Soviets, which had a flawed economic model.

Another emphasis in your argument is perestroika. If the Soviet economy "was, for the most part, 'well' and developing," there was no reason to carry out perestroika in the first place.

Do you know why Gorbachev came to power?

Gorbachev came to power determined to promote several reforms to keep the Soviet Union afloat. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union found itself in a very delicate situation. The Soviet economy was in a severe crisis, with the country accumulating deficits due to high spending.

None of this has much to do with your claim that the Soviet economy is "backward" or "stagnant".

USSR having worse conditions than Western Europe has been a fact for basically its entire existence.

Vietnam is a worse place to live in than Japan or Korea. Which economy is more "stagnant"?

And no, there are very few nations that were as thoroughly destroyed as USSR. Moreover, even among States that did really well, some did better than others and the USSR wasn't horrifically behind other developed States. So this argument just doesn't hold water.

The Soviet economy was dependent on oil exports, and due to the drop in the price of this commodity on the international market, Soviet revenues began to plummet. Furthermore, Soviet agriculture suffered from low yields, forcing the government to export grain from foreign markets. The Soviet government also saw its economy bleed due to excessive spending on the Afghan War.

Politically, there was also strong popular dissatisfaction with the Soviet government, mainly due to the poor performance of the Soviet economy.

The fact that you say that until 1986, things were going well for the bloc economically is quite funny, because none of that is true. For example, using the example of motor vehicle production in the USSR increasing before Gorbachev and then decreasing with the implementation of Gorbachev's reforms is even funnier.

Things were going quite well for the bloc.

Domestic perceptions of "backwardness" and envy at Western European living standards is understandable, especially when we look at consumer goods. Moreover, many parts of the country were much more rural and less developed than others.

Your remark that "none of that is true" is really just more of the same prattle about how USSR was just horribly backwards and terrible to live in, when it's not remotely true. In a globe full of actual bakcwards, stagnant, deteriorating, and even rapidly developing the USSR was a firm "second place" to live in after the "First World". The bloc had done an amazing job with literacy, minimizing poverty and even homelessness. Things you cannot necessarily put a value on. But that's one of the issues with common goods. It's very hard to put a GDP number on these things.

Do you know why this happened?

You yourself ended up answering in your comment. Here's your comment:

The problem with central planning is not the inability to produce competitive products.

I recommend you read the book "Icon" by Frederick Forsyth. In the book, he gives several descriptions of how the Soviet shadow economy worked. This economy was excellent for allocating scarce resources to which it had access, but manufacturing scarce resources was another matter. The book also shows how several Russian millionaires "magically" emerged after the end of the USSR: they were people who accumulated hard currency in the informal market by selling food or gasoline during the communist years. These people eventually became the Russian mafia. This is why today it is speculated that the black market always represented 40-50% of the entire Soviet economy.

If it's really just more of the same then I'm not interested. I'm well read on the Western perspective on the Soviet economy. I don't consider this perspective useless, but it's really just the same thing as you're saying.

Incessant whining and criticism about the Soviet Union and how bad it was. Focusing on dissidents and critics and never the other way around.

The reality for the Soviet citizen is that the vast majority had a steady job, secure shelter, and a disposable income. The country provided a solid improvement year on year to the average citizen. All of that disappeared, replaced by political instability, destructive economic change, and a very difficult decade in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse. Soviet nostalgia was sizeable even into early 2000s.

Not that the USSR didn't have it's problems, one of the main ones being poor at measuring its own economy.

It is well known that since the end of Brezhnev's rule, the Soviet economy had been stagnant. Andropov took office promising economic reforms to stem the economic crisis and the stagnation of the Soviet standard of living. There is no shortage of articles analyzing the descriptive scenario of the Soviet economy at the time:

Andropov died prematurely. He remained in office for months, promising to embark on a set of economic reforms. But like all failed Soviet planning, several Soviet economic experts believed his modernization program could be undermined by the entrenched central planning bureaucracy. This was the fate of the Brezhnev-Kosygin of 1965-70.

No, it's well known that there is a perception of the USSR being stagnant and backward. Dooming about your own country is a practically a cultural feature of Russian history.

Many Russians to this day believe that their country is horribly stagnant and backward, despite much evidence to the contrary.

This is like talking to Kasparov about Russia. There will be no end of criticism despite evidence to the contrary.

Present Japan is artificial country created and sustain by combined efforts of US and Gulf Royals. where did the first Toyota Land Cruiser got exported? where that Toyota Taxi with large capacity engine started? who owned the first Lexus dealers.Why are you claiming twice the emphasis on the destruction of the USSR in WWII?

Do you know which countries also emerged from WWII destroyed?

Japan.

Basically almost all of Europe, and especially West Germany.

Do you know what they have in common? They all had a higher standard of living than the USSR.

Yeltsin in Kazan. that was the end of USSR. no amount of GDP growth could have save it. and yes 1917 revolution could not be stopped as it was supported by people of high intellect. i am sure you know it. Thats why when i mentioned Russian empire/Soviets were only empires in history that faced combined forces for longest time. and despite all the bad conditions Russia was and is fully developed country. Its B and C team in Maths and hard sciences olympiad could easily beat its Western counterparts even when West was at its peak

Putin certainly can say USSR was less wealthy and backward compared to Western Europe overall but there was Excellence that goes far beyond West

Putin very polite and sophisticated person. He can say any things up to justify current condition and any lack of improvement under his term. He created this Nashi movement to find out what kind of Post Soviet generation in Russia. if Putin has positive opinion about Russians he would not have built so many Mosques and thats the reason i think he keep them even more poor untill they learn those values.

Thank you in advance for your reply!You need to consider the economic context.

The Soviet regime's preference for scarcity over inflation has its roots in the hyperinflationary history of the Soviet economy. By the mid-20th century, Soviet planners were well aware of the dangers of hyperinflation. With the end of the Tsarist regime and the conclusion of World War I, the new socialist regime took control of a country that was already bankrupt and highly dysfunctional. Hyperinflation soon followed. The Bolsheviks attempted to abolish money altogether, but this naturally failed, and a series of monetary reforms followed. By the late 1920s, however, the regime was engaging in widespread price control efforts, including the highly unusual tactic of rationing in peacetime. This limited price inflation for many goods and set the stage for the "suppressed inflation" that would become a pillar of the Soviet system for decades. Prices, however, began to rise rapidly in many areas, and World War II brought a new wave of price inflation, and prices soared. This was followed by another monetary reform—namely, the devaluation—of the Soviet ruble in 1947. Price control efforts were redoubled, and overall prices actually fell during the 1950s.

For much of the 1950s and early 1960s, the regime was perpetually concerned about price inflation. Indeed, Soviet ideology stipulated that inflation did not actually exist in the USSR. As Vasily Garbuzov, the Soviet Finance Minister, stated in 1960:

This is propaganda, of course, but in a sense, Garbuzov was right. A socialist state could indeed moderate the effects of monetary inflation on prices by reducing living standards and consumer choices whenever prices appeared to be rising.

This was necessary because the money supply continually expanded as wages rose. In their 1985 study of the Soviet economy, Igor Birman and Roger Clarke wrote:

In an unencumbered economy, wages are closely tied to worker productivity, so wages would not rise disproportionately to the quantity of goods and services available in the economy. In a socialist economy, however, the price of labor—that is, wages—was arbitrarily set like all other prices. Wages under socialism are also paid by the public treasury and can be raised at the regime's convenience. This often meant wage increases because higher wages were politically popular. Rising wages potentially created the impression of prosperity, even when the economy was not actually more productive. Furthermore, as Birman and Clarke note:

Increasingly, after 1965, the Soviet money supply became disproportionate to the economy's productive capacity. In a relatively free economy, this would quickly lead to price inflation, but the Soviet regime had ways to shift the economic burden elsewhere.

Thus, prices were kept under control not through fiscal discipline but through price controls. This led to shortages because, if wages rose while product prices did not, demand quickly outstripped supply. Soviet citizens often found they had very little to spend their money on, resulting in the long lines and empty shelves we associate with the Soviet economy today.

Through this mechanism, the regime could continue to inject new money into the economy, but also prevent ordinary people from spending "too much" money and thus raising consumer prices. The downside, of course, was that living standards fell considerably, as historian Steven Efremov :

The result was essentially forced savings. Efremov continues:

In some respects, this was beneficial for the regime, as these unspendable savings could also be used to purchase government debt. But this accumulated money—known as the "monetary surplus"—increased much faster than the production of goods and services, and Efremov concludes that "the money supply had grown far more than was necessary for regular circulation." This would come back to haunt the regime when the economy began to open up and consumers were finally able to spend their money, causing prices to soar.

An additional method of reducing official inflation figures was subsidizing consumer goods. Retail price subsidies were introduced in the Soviet Union in 1965 as part of a major package of economic reforms. Soviet authorities then began implementing price subsidies on "basic foodstuffs such as meat, milk, bread, sausages, sugar, and butter." The goal was to keep prices stable. These subsidies survived subsequent economic reform efforts and became an increasingly large part of the economy in the early 1980s, with government spending increasing rapidly to put downward pressure on prices through subsidies.

None of this actually helped Soviet living standards.

To counter the effects of monetary expansion and falling living standards, the Soviet regime relentlessly tried to increase production to reduce the gap between monetary growth and productivity growth. However, due to the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism, Soviet central planning failed to coordinate goods and capital efficiently, and worker productivity stagnated.

Another result was an even greater decline in government revenue collection. Although taxes were levied and some revenue could be raised from imports, government monopolies—that is, state-owned enterprises—that controlled a variety of goods and services produced much of the income on which the regime depended. These enterprises could theoretically increase their revenues by increasing production, but production often stagnated as wages—that is, production costs—rose.

Government budgets, therefore, increased in tandem with falling revenues. Byung-Yeon Kim notes, for example, that "retail price subsidies…increased from 4 percent of government budget expenditures in 1965 to 20 percent in the late 1980s."

However, the availability of consumer goods certainly did not keep pace. Instead, consumers had few places to spend their money, and "the share of forced savings in total monetary savings increased from 9 percent in 1965 to 42 percent in 1989."

The truth is that indicators such as GDP-PPP are utterly crude and were invented to conceal the metaphysics of the so-called “economic science” of liberalism — that is, of capitalism. Like many other constructs that dominate the economic jargon, they serve to theorize deceit and exploitation. Beyond that, a socialist system is not something fixed or predefined that can be neatly described. Not even Marx attempted to do so. His greatest work, Capital, is where he exposes the contradictions and malfunctions of the system — it is a thorough critique of capitalism, something like “notes on what to watch out for” when attempting the next step.

Thus, as fate had it, the Soviets were called upon to answer questions unprecedented in history. That is why they experimented even under conditions without money. For a truly socialist economy to exist, the law of value must be abolished, so that the economy can be viable. Imagine a kolkhoz producing vegetables in Siberia and another one outside Moscow. In a market economy, the one near Moscow has a huge commercial advantage, which — to be neutralized — requires the elimination of the law of supply and demand. All products would need to have stable prices everywhere across the country. But the existence of money — by nature inflationary, especially in the capitalist phase where money itself becomes a commodity — complicates the process even further. Money reflects a greater value than what circulates in the market, in order to generate the motion of the supply–demand cycle. Adding to this the Kosygin pro-market reforms just added fuel to the fire. Now imagine an economy that, while capable of producing surplus value, cannot store it due to the prohibition of private property or storage of value. What does it do then? It reinvests it into the economy itself. And that didn’t please some people, they wanted to dip their whole hand into the jar of honey. In my view, institutionalization and the lack of motivation and imagination were the essential causes of the USSR’s decline. It’s understandable, things can’t go perfectly the first time.

Moreover, Western indicators conveniently forget to mention that since Khrushchev’s era, a large part of the Soviet economy already implemented a 7 hours day work. How much does it contribute to PPP when a person can take 12 days of vacation thousands of kilometers away, by plane, for free? How much do fully free healthcare and education contribute?

What would the “annual meat consumption index” show if it accounted for the free meals provided at workplace canteens in every sector of Soviet labor? And what about free meals, free kindergartens and nurseries? You can’t just measure all that through GDPvsGDP or PPPvsPPP, nor through degenerated notions like “productivity.” Only if we agree on what we mean by productivity can we even begin to have a meaningful conversation (and of course, this remark doesn’t refer to you).

Last edited: