I doubt there'll actually be a major deindustrialisation in Europe. Maybe industrial production is going to drop by a few percent, but Europe can afford to bail out bankrupt companies, even if it turns them into zombies. The biggest danger to the EU economy is the lack of investment. For a period of at least 2 years, nobody is going to invest in Europe. Europe may only decline a little in industrial production, but more importantly it will miss out on future growth. China and America are going to take more global market share while Europe is in hibernation. The world doesn't wait for anyone, if you stop running, you're falling behindWithout cheap energy Europe will lose all its heavy industry and they will be relegated to assembly of final products.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

European Economics Thread

- Thread starter PiSigma

- Start date

supercat

Colonel

Sanctioning Russian aluminum may really deindustrialize Europe.

China actually had a "COVID quarter" in Q2 this year.China had its "COVID Year" in 2020 but they got back on track by Q3 2020 latest, we in europe can't lift our asses out of this mess so easily. It is one thing to stop an pandemic, it is a whole other thing to replace 30% of your energy demand.

Poland has 17.2% inflation, almost the same as Russia had at the height of sanctions.

Millions of Britons will be forced to pay 40% tax on their earnings due to the British government's new plan for finance. By the 2025-2026 fiscal year, about 7.7 million people will pay the higher tax rate.

During the first nine months of 2022, Europe's LNG imports from Russia increased by 50%. Some EU countries that previously imported no or only small amounts of natural gas from Russia now receive regular shipments of Russian LNG. This is explained by the LNG structure that was assembled for the coming of American shale gas, but some realized that it pays more to use Russian LNG, because it is much cheaper.

Source: 20LNG%20Sore,Highs%3B%20Supply%20Mostly%20from%20Arctic&text=During%20the%20first%20nine%20months,Russia%20increased%20by%2050%20percent

Last edited:

The Aluminum situation is starting to get serious, the Romanian refinery is already dead and the Irish one looks like its next. You lose refineries you also start losing smelters, which affects your ability to create specialty alloys. You lose special alloys a good chunk of high-tech manufacturing gets hit, airplanes, ships, automobiles satellites be seriously affected.Sanctioning Russian aluminum may really deindustrialize Europe.

China actually had a "COVID quarter" in Q2 this year.

Bookmarked this thread, has overtaken the Indian Economics thread in entertainment value.

So the end result of decoupling is Europe will become China's assembly workers?Without cheap energy Europe will lose all its heavy industry and they will be relegated to assembly of final products.

China actually had a "COVID quarter" in Q2 this year.

Germany will have the No Energy decade

@european_guy there you have it bro, The Dutch gov't will not heed the US in restricting ASML from selling DUVL to the Chinese, a matter of fact they may allow the export of EUVL maybe in 2024 to give ASML a heads up before the introduction of a Chinese EUVL. in 2025.

this can be related to ASML as well.

interesting development.

I didn't know of this (of course no info on mainstream media). Here is my take on another very important, even more important event that is now taking place. A bit OT...but no so much, becasue it will have a deep effect also on semiconductors world.

Germany's Scholz decided to visit China although he knows this will piss US greatly.

Now all EU leader will sit at the window and see what happens next. If US succeeds in provoking a political crisis and remove him, and place one of his shills instead (like the current foreign minster that is very pro-US), then everybody in Europe will be scared and will not dare to oppose US. This would be a huge victory for US.

If instead nothing happens to him and he survives, then other leaders very quietly and very smoothly will follow Scholz example.....and US will start to hear some crack on the wall.....

Scholz very brave!

He is well aware of what he is doing, but he is doing it nevertheless, because he thinks is in the interest of his nation.

Scholz very brave!

He is well aware of what he is doing, but he is doing it nevertheless, because he thinks is in the interest of his nation.

And Scholz thinks it is in the interests of Germany because the companies are telling him this.

The Financial Times London have a writeup on this below.

Basically China is 50% of the global chemicals market and over 55% of the electric car market.

If BASF and the German automakers don't go into China, someone else will serve this demand.

And that someone else (probably a Chinese company) will become a more formidable competitor in the global marketplace

---

archive.ph/TQPmg

ft.com/content/097b24ba-a967-45d9-a476-6aff268bc7b5

China-bashing will get Europe nowhere

The bloc needs to create an environment that will enable its companies to outcompete global rivals

Enough China-bashing, said Martin Brudermüller, BASF chief executive, last week as he reacted to critics of the group’s plans to expand in the country while downsizing in sluggish Europe.

Instead of fretting about the chemical giant’s $10bn investment in China, Europe would do better to examine its own “deficits and weaknesses”, he said.

Brudermüller, who is leading a trade delegation to China with German chancellor Olaf Scholz this week, is not wrong. European industrial companies struggle against some pretty fierce headwinds — not just the unusually high energy prices that have forced the shutdown of swaths of energy-intensive industrial production since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

There are also the mounting costs of Europe’s green ambitions, the accompanying web of environmental regulation and the unfinished project of the single market. All these can make life difficult when facing competition from countries with plentiful and cheaper energy supplies, looser regulations or more consistent and generous government support for business.

But BASF’s decision to build a state of the art integrated chemicals plant in China — rivalling its unique Ludwigshafen facility in Germany — is no simple substitute for a lack of growth or competitiveness in Europe.

Designed to run entirely on renewable energy, the plant is the latest sign that China, once content to be the world’s factory, is fast becoming the world’s innovator with the help of some of Europe’s biggest companies.

The old trade bargain that allowed European companies to access China’s vast market while still retaining control of the most innovative technologies is changing and the longer-term consequences could be serious for Europe’s industrial base.

Just look at the example set by Germany’s carmakers. Despite rising global tensions over Beijing’s claims on Taiwan and the risks that poses for operations in China, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen and BMW have substantially stepped up research and development investment there, according to a study by think-tank Merics.

The investments have been spurred by China’s support for electric vehicle development. Today, 55 per cent of all EVs are sold in China, and if Germany’s carmakers are to remain competitive globally, they have to access not just the country’s consumers but the technological expertise that has been developed there.

In the decade from 2007 to 2017, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen and BMW set up just five R&D centres in China. But in the four years since 2018, they have opened 11.

“China is not only a sales market for Germany’s carmakers; it has become the world’s leading EV market, and it may well be the linchpin for their global competitiveness,” says Merics’ Gregor Sebastian, author of the report.

Along the way, German car companies have integrated Chinese suppliers into their global supply chains, sought out China’s tech companies for software partnerships and begun developing new models for export to the global market from the country. The result has been the creation of new players no longer content to sell just in China, but ready to compete globally, with consequences for supply chains that stretch across Europe.

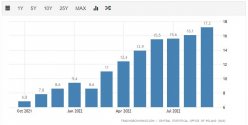

The decisions to innovate in China’s growing market are not irrational. For companies such as BASF, there may even be little alternative. Europe, hobbled by high energy costs, has seen its share of the global chemicals market fall almost a fifth over the past decade to 14.4 per cent and it is predicted to decline to just over 10 per cent by 2030. This year, Europe became a net importer of chemicals by value as well as volume for the first time, implying that even its traditional strength in the speciality segment is eroding.

Meanwhile, China will account for close to 50 per cent of global chemical sales by 2030. If BASF isn’t there to exploit that growth, someone else will take its place.

But even as BASF doubles down on China, it has thrown out a challenge to European policymakers. It is not enough for Brussels to focus on buoying up a select few strategic sectors deemed critical to Europe’s industrial autonomy. Europe urgently needs to address wider barriers to competitiveness.

Brudermüller is right. China-bashing will not stop the inevitable. The focus now has to be on creating the conditions that will allow European companies to outcompete the very rivals they have helped to create.