Semiconducting nanomaterial for curves holds promise for Internet of Things and wearables, says Hong Kong-led team

- Scientists say nanomesh can be made at much lower temperatures than existing semiconductors and on common materials such as paper and plastic

- The researchers used tellurium, a semi-metallic element that can be mixed with other metals to form alloys

Published: 6:02pm, 23 Jun, 2023 Updated: 6:32pm, 23 Jun, 2023

A team of Hong Kong-led scientists have developed a new way to produce a semiconducting nanomaterial that say can be made into sensors on curved surfaces to create safer infrastructure and advance flexible

.

They said the nanomesh – formed from a network of nanowires – could be manufactured at much lower temperatures than for existing

and grown on common materials such as plastic and paper, reducing production costs.

The team from City University of Hong Kong, the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Zhengzhou University, Beijing University of Technology and Kyushu University in Japan published their findings in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications in April.

Semiconductors are silicon-based devices made up of hundreds of millions, and in some cases billions, of transistors, which act as tiny “switches” to control the movement of electrons.

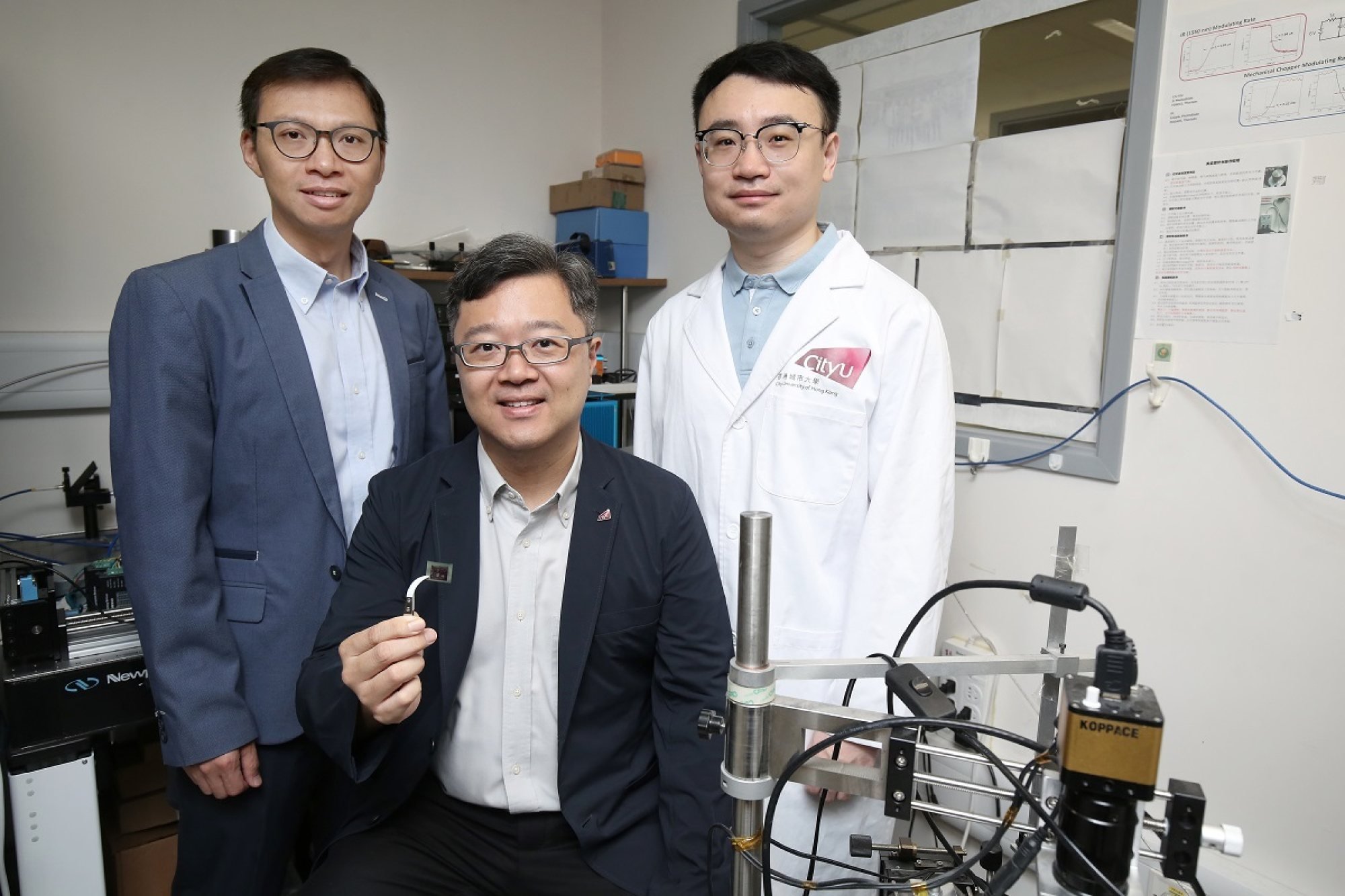

CityU’s research team (from left) Dr Alex Wong Chun-yuen, Professor Johnny Ho Chung-yin and Dr Meng You. Photo: Handout

A semiconductor conducts electricity under some conditions but not others, making it a good medium to control electrical current. Most of the world’s semiconductors, also known as integrated circuits or microchips, are made from pure elements such as silicon extracted from sand.

In the recent study, the researchers used tellurium, an emerging semiconductor material. The element is semi-metallic – it can be controlled to act as a metal or semiconductor. It can be mixed with other metals to form alloys.

Lead author Johnny Ho Chung-yin, a professor in the department of materials science and engineering at CityU, said tellurium had a unique structure made up of spiral chains of atoms bonded by van der Waals force.

The force enables tellurium nanomeshes to self-weld and grow on rigid, flexible or curved surfaces. The self-welding process boosts the performance and mechanical robustness of electrical devices, according to the study.

“Thanks to van der Waals forces, we can grow the nanomesh on any substrate without worrying about defects in the material that could arise from being grown on an unsuitable substrate,” Ho said.

To create the nanomesh, the team first vaporised tellurium source powders and carried them to a base material, such as silicon oxide, polymers (stretchable plastics) or paper, where they were heated at 100 degrees Celsius (212 Fahrenheit) and grew. The temperature is far lower than the required 600 to 700 degrees using conventional methods.

Ho said the nanomaterial was promising for applications in the

(IoT) – the network of physical objects embedded with sensors, software and other technology to collect and share data.

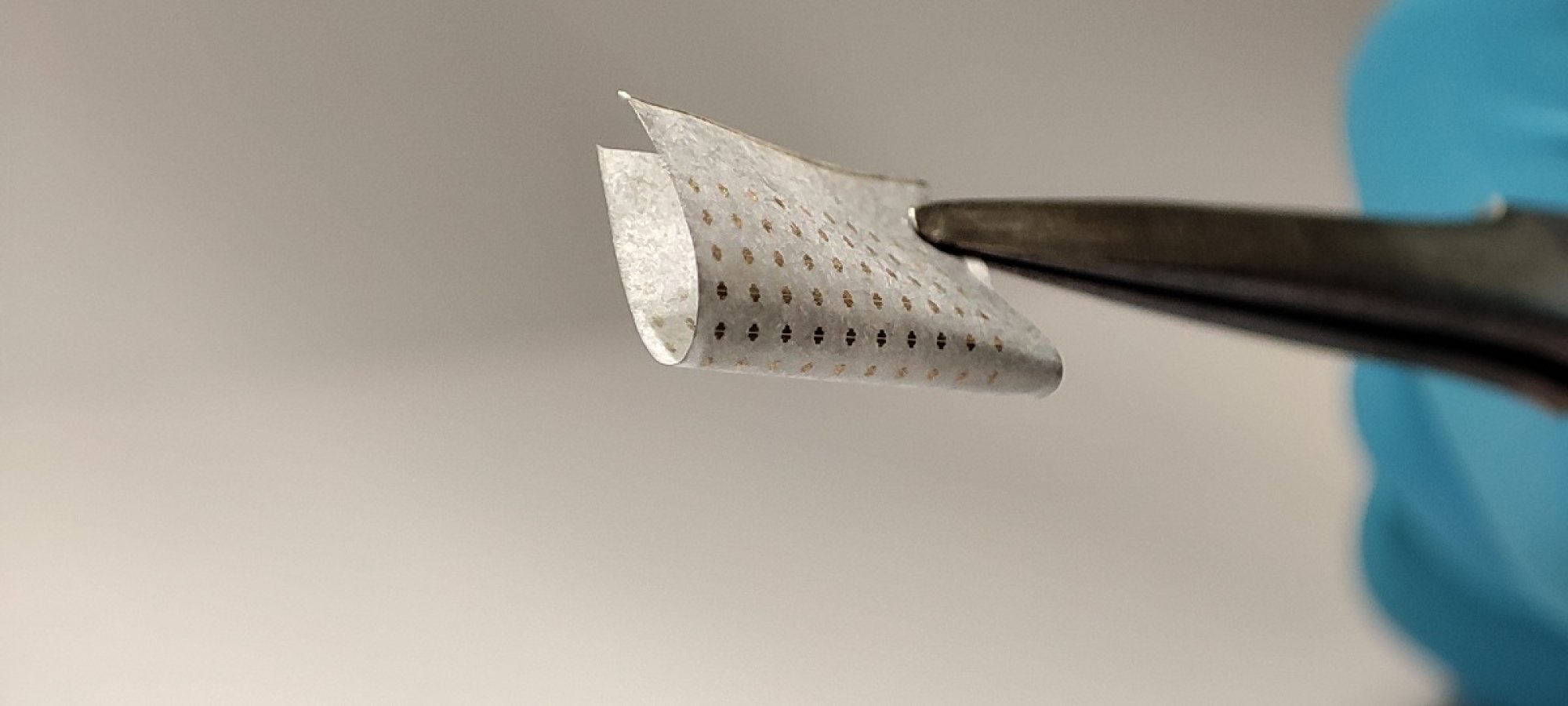

Low-cost nanomesh infrared photodetectors fabricated on paper. Photo: Dr Meng You, City University of Hong Kong.

“Sensors can now be made with a flexible material for them to be deployed on curved surfaces like parts of a bridge. We can deploy sensors – as many as needed because they can be manufactured at low costs – to measure the amount of pressure the bridge bears, alert staff to areas where repair work is needed and ensure its safety,” Ho said.

He added that the data collected could be analysed in real time to reflect the structural safety of infrastructure and aircraft.

The nanomesh could also be used to build night-vision cameras which emit infrared light that is reflected off objects and detected by their sensors, Ho said.

Alex Wong Chun-yuen, an associate professor of chemistry at CityU who co-leads the research, said the cross-disciplinary project started when Ho, his long-time collaborator in material sciences, raised an issue that could potentially be addressed by the field of chemistry.

“As chemists we study the characteristics of the elements and are capable of manipulating the reaction conditions of the basic material,” he said, adding that his synthetic chemistry team helped ensure the manufacturing process could be replicated.

The team said they would continue to work on the nanomaterial and were experimenting with creating metal alloys with tellurium.