Western msm still whining about China and deflation. What could it mean?

Updated link

Xi Digs In With Top-Down Economic Plan Even as China Drowns in Debt

Xi Jinping is bracing for a showdown, sticking with economic policies aimed at making China the world’s most powerful country.

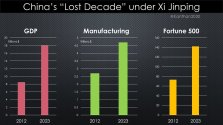

Some are calling it a “Lost Decade.”

More than 10 years into the Xi Jinping era, it has become clear that much of China’s growth under his watch was driven by unsustainable borrowing, real estate speculation and investments in factories and infrastructure the country didn’t really need. Difficult reforms that could have unlocked more durable growth, such as steps to increase consumer spending, were neglected in favor of policies designed to bolster Communist Party control.

Now, China is drowning in debt, reeling from a property bust that wiped out trillions of dollars of household wealth, and verging on a deflationary spiral. Growth has slowed, Western investment has collapsed and consumer confidence is near a record low.

And yet, as China squares off with the U.S. for a second showdown over trade, Xi is digging in. He’s convinced that his top-down approach to managing China’s economy, with plans to make it an even bigger industrial power, offers the best path for China to eventually surpass the U.S. in economic might.

People close to Beijing’s decision-making say nothing that has befallen China in recent years has changed Xi’s belief that the U.S. is fading as the singular superpower, and that China’s importance is rising on the world stage.

“Xi still believes that the East is rising and the West is in decline,” said a foreign-policy adviser in Beijing, referring to a pronouncement the leader made three years ago when China’s economy, driven by Western demand for its exports, experienced a short-lived recovery from the Covid pandemic. “It might just not be a straight line in his view.”

To achieve his vision, Xi is building out a sweeping industrial supply chain intended to make whatever China needs, including semiconductors, to withstand more conflict with the U.S.

His government is also drawing up plans to hit back at any tariff hikes by President-elect Donald Trump, through retaliatory measures such as restrictions on sales of raw materials the U.S. needs to make chips, car engines and defense-related products. He’s cultivating allies in the developing world to try to add pressure on the U.S.

What Xi hasn’t done, many economists argue, is take hard-but-necessary steps to fix the country’s wounded economy.

While Beijing has rolled out some stimulus recently, it hasn’t acted decisively to clean up the troubled property sector, fully restructure local-government debt, and significantly increase consumption, which would support growth in the long run.

“A lot of the problems are of the government’s own making,” said Richard Koo, chief economist at Nomura Research Institute. Like many economists, Koo believes China faces what he calls “a race against time” to address the country’s mounting growth problems before it slips into a long-term downturn, made worse by unfavorable demographics.

The State Council Information Office, which handles inquiries about China’s leadership, referred questions to the country’s top economic-planning agency, China’s central bank and the ministries overseeing industry and commerce. None of those government institutions responded to questions.

Following Xi’s moves

I had a front-row seat over the past decade covering China as Xi had opportunities to fix its economy, just as previous Chinese leaders did when they faced economic turbulence.

Every time, he took the fork in the road that led to more state control, and away from the kinds of changes that many Chinese economists say are necessary. Although some of China’s economic problems started before Xi was in power, he failed to resolve them, leading even some of the government’s own advisers to talk privately about a lost decade.

In September 2018, I attended an economic forum at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing. At the time, some market-minded officials hoped that Trump’s tariff threats would force Beijing to carry out long-delayed reforms such as giving private enterprise more room to prosper.

The government needs to “build consensus through debate and then implement reforms one by one,” said Wu Jinglian, a pro-market economist.

Zhang Shuguang, another liberal thinker, reminded the audience that Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who launched the country’s “reform and opening” era, focused on integrating China with the U.S. and other developed countries.

“Necessary concessions should be made,” he said, while cautioning against matching Washington tit-for-tat in an endless trade war.

Instead, the trade fight galvanized Xi’s resolve to expand state control and plump up Chinese industry, even though it risked worsening tensions with the U.S.

His government showered preferred sectors such as semiconductors and electric vehicles with subsidies and encouraged banks to lend more to factories to increase production.

Xi also launched a crackdown on the private sector. Meant to discourage irrational risk-taking and knock powerful business leaders down a peg, it wound up stifling China’s entrepreneurial spirit.

The result was an economy increasingly dominated by state-backed firms, with growing overcapacity of steel, EVs and other products. Today, China is more reliant on exports to drive growth than in 2018, making it more vulnerable to the kind of tariffs Trump is proposing.