And please tell me whose mistake it was ?His entire election was just a mistake.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chinese Economics Thread

- Thread starter Norfolk

- Start date

And please tell me whose mistake it was ?

He's so naive. I dont think he has heard of the saying "we get the politicians we deserve"

He's so naive. I dont think he has heard of the saying "we get the politicians we deserve"

Hell this is the luckiest guy in the world. 33 year old billionaire from designing toys. Man. World's unfair. I wish I were him. Becoming a billionaire designing toys

Big or small, there is no data supporting. If you talk about Chinese in Indonesia then there are below 2%. Chinese concentrated in big cities, that is why you think a lot of Chinese in Indonesia.

Pork can be found rather easy in some big cities, but not all province capitals have it, if you talk about Tier 2 cities, then it will be difficult.

Except North Celebes, Bali, West Borneo ( Papua and Riau i don't know ) and some concentrated Chinese area, Traditional / wet market in Tier 3 cities does not provide pork.

Pork scarcity is becaused 87% Indonesian are Moslem ( The percentage is a lot of higher than Malaysia ).

.

If you said before 1998, Chinese controled over 70% ( maybe 80-90% ) economy, I would agree, but nowadays it is very different.

The slogan " why chinese which below 2% can control 70 % Indonesia " is launched by anti-Chinese movement, and ridiculously some Chinese believe it.

Today Chinese still control a big portion of Indonesia economy but 70% is definitely exaggregated.

You can see from Indonesia stock exchange, before 1998, Chinese conglomerates/ taipans dominate them, but nowadays only BBCA ( previously held by taipan Sudono Salim/ Liem Sioe Liong now overtaken by Jarum group ) and Gudang Garam ranks in highest 10

Indo Chinese here. Pork is widely available in all major cities like Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung, Balikpapan. Esp Sumatera Island because there is a huge Batak population.

Pork discussions are fun and all but let’s get back to topic please.

D

Deleted member 15887

Guest

For multiple years, electronics companies that sell into the U.S. market have faced pressure from tariffs to move their supply chains out of China. Savvy companies sought loopholes by moving small pieces of their supply chains, but most stayed put. There was talk this spring when development schedules and production lines ground to a halt that maybe Covid would inspire companies to rethink their reliance on China (or any single-point-of-failure element to their supply chains).

For consumer electronics companies, fall is the beginning of new product cycles for 2021, and an opportunity to choose different manufacturing partners in different locales. The story remains the same: companies are choosing to work with trusted partners and aren’t making big moves out of China.

Earlier this year, the opinion was clear: the combination of tariffs and Covid would push manufacturing out of China. Material Handling and Logistics, a supply chain trade publication, wrote in June, “A survey by Gartner of 260 global supply chain leaders in February and March 2020 found that 33% had moved sourcing and manufacturing activities out of China or plan to do so in the next two to three years.” Sarah Brown, of the MIT Sloan School of Management, wrote in July, “The new coronavirus has put a spotlight on the world’s reliance on Chinese manufacturing, and prompted speculation that supply chain restructuring might start with pulling out of China.”

This hasn’t happened.

Instrumental provides software to support manufacturing lines for top electronics companies. We did a retroactive analysis across multiple years of deployment data to see if there were any indications of a shift. The major trends remained the same:

Large electronics brands with complex products generally built in China in 2020 and plan to do so again in 2021

Medium electronics brands split roughly in half between building in China and building in Taiwan, with a slight trend towards Taiwan in the 2021 plan

Small electronics companies working on first or low volumes products are building in the U.S. and plan to do so in 2021 as well

Where did all of the momentum for supply chain shift go? Manufacturing folks are pragmatic and practical people, and their primary job is to mitigate risk. In general, unless there’s a compelling business reason, manufacturers will default to the lowest-risk option.

This fall, teams evaluated virus risk, partner risk, and socio-political risk. On virus risk, China and many parts of Asia have maintained strong virus control, so mass shutdowns of the variety we saw in early 2020 seem incredibly unlikely. Switching manufacturing partners, even within the same company (from a Shenzhen-based team to a Vietnam-based team) would be considered a large partner risk. Typically partner risk is assessed during choreographed factory tours, team meet-and-greets, and in person work sessions. With restricted travel, de-risking new partners has been incredibly difficult – so most have opted to work with teams they know. For socio-political risk, which includes everything from tariffs to degrading political relationships, it’s been anyone’s guess.

Given this, it’s not surprising that there hasn’t been a huge shift of electronics supply chain out of China for the 2021 season. Instead, supply chain leaders are focusing on execution risk: how can they make 2021’s new programs successful in spite of continued challenges from Covid, such as restricted travel and distributed teams all trying to collaborate remotely in real-time. For many, they’re expanding their toolkits to include technology leveraging cloud platforms and data analytics to increase agility and to mitigate general execution risk – so they are able to execute no matter what the next disruption is. One leader at a Fortune 100 electronics company summed it up, “In the spring, we just had to react and make it work, but this year, we’ve got to have a plan.”

"DeCoUpLiNG!" amirite XD. Looking back, so many of the articles written on this back in May-July just seem childish tbh

"DeCoUpLiNG!" amirite XD. Looking back, so many of the articles written on this back in May-July just seem childish tbh

They know if they left they would lose competitiveness against Chinese and other companies in China.

That is also the case for China. Debt this year was up bigly. But the USA printing machine went to stocks and paycheck for people, Chinese to infrastructure, and industry.It is the US that has been printing money. This is not the case for China.

‘Made in China,’ Once a Badge of Derision, Finds New Fans—in China

In 2008 at least six babies died and 300,000 fell ill after drinking made-in-China infant formula tainted with toxic chemicals. In response, many Chinese parents embraced foreign brands, catapulting the likes of ’s Aptamil and s Illuma to the top of the market. Yet for the past two years, the leading formula brand in China has been made by , a Beijing company that emphasizes its local roots rather than seeking to obscure them. “More suitable for Chinese babies,” the company’s advertising boasts.

In categories ranging from baby food and bottled water to sportswear and skin cream, Chinese brands are putting pressure on global rivals that depend on the country for much of their growth. While increasing nationalism has boosted the momentum of domestic products for the past couple of years, the Covid-19 is hastening the shift. With prices typically lower than foreign brands’, domestic products have increasing appeal in times of constrained household budgets, and the growth of online sales has weakened the multinationals’ advantages in distribution and marketing. “Chinese shoppers are showing stronger confidence in local brands,” says Helen Wong of , which has backed local startups such as lingerie maker Neiwai and cafe chain Coffee Box. “The coronavirus is accelerating the trend as people stay home, watch livestreaming, and shop.”

Investors have piled into domestic companies that are overtaking multinational rivals, doubling the combined value of China’s 500 top brands in the past four years to about $3.8 trillion, according to marketing consultancy World Brand Lab. Clothing and shoe manufacturer Anta Sports Products, which in 2018 passed to become China’s No. 2 sports apparel brand behind , is up more than 50% this year even as the benchmark Hang Seng index has fallen 6%. Shares of China’s biggest bottled water brand, , have more than doubled since its September Hong Kong trading debut. , owner of cosmetics house Perfect Diary, a growing threat to the likes ofand , has jumped 75% since its U.S. initial public offering in November.

Local names account for seven of the top 10 cosmetics brands, up from just three in 2017, according to market researcher Daxue Consulting. L’Oréal SA’s Maybelline makeup line has seen its share in China plunge, to 9.1% last year from more than 20% in 2010, according to Euromonitor International. In the skin care and lotion category, the share of L’Oréal Paris dropped, to 4.5% last year from 5.6% in 2014, putting it neck and neck with local brand . The growing strength of Chinese cosmetics makers can be traced to their smart online strategy, according to Derek Deng, a partner in Shanghai with Bain & Co. “Insurgent Chinese brands are more likely to be digital from Day One,” he says, while multinationals tend to favor physical stores.

Perfect Diary, launched in 2017, now stands just behind several European-owned brands, with 4% of the crowded market for so-called color cosmetics such as lipstick and mascara, Euromonitor estimates. Its advertising stresses that its products come from the same manufacturers as Dior, Lancôme, and Armani but sell for less than one-third the price. It’s teamed with ’s Oreos for a skin foundation cream (no, it doesn’t contain ground-up cookies; the box looks like an Oreo). On Singles Day, the Nov. 11 organized by , Perfect Diary’s online store included livestreams of influencers pitching products such as animal-themed eye shadow (co-branded with the Discovery Channel) featuring colors and packaging inspired by rabbits, deer, and fish. “We’ve proven we can stand out in a highly competitive market,” says David Huang, chief executive officer of Yatsen.

Foreign brands aren’t finished in China, of course. They dominate categories such as high-end handbags and luxury cars. Estée Lauder Cos. sold more than 2 billion yuan ($300 million) of products on Singles Day with a livestreaming campaign, two-for-one discounts, and installment payment plans. And —still the biggest fast-food chain in China—is supplementing its fried chicken with products such as fast-cooking stinky sour snail noodles to cater to diners stuck at home in the pandemic. “The attitude of big international brands is changing significantly,” says Wu Wenmi, founder of Wenzihui MCN, an agency in Hangzhou that partners with Alibaba. “They are more humble now and willing to hear our opinions of how to play the game.”

One way Chinese companies are playing the game is with marketing that resonates for locals. While foreigners’ ads stress the nutritional value of their infant formula, Feihe nurtures relationships with consumers via loyalty programs, new-parent support groups, and collections of bedtime stories. And Chinese brands are increasingly tailoring their wares to domestic tastes. , for instance, is stepping up sales of innovations such as pineapple-flavored cheese and squid-infused snacks in addition to its lineup of basic milk and fruit yogurts. “Foreign brands were so innovative three decades ago when they first came to China,” Mengniu CEO Lu Minfang said at a November media briefing. “But now they’re developing slower than local brands.” —Bruce Einhorn and Daniela Wei

In 2008 at least six babies died and 300,000 fell ill after drinking made-in-China infant formula tainted with toxic chemicals. In response, many Chinese parents embraced foreign brands, catapulting the likes of ’s Aptamil and s Illuma to the top of the market. Yet for the past two years, the leading formula brand in China has been made by , a Beijing company that emphasizes its local roots rather than seeking to obscure them. “More suitable for Chinese babies,” the company’s advertising boasts.

In categories ranging from baby food and bottled water to sportswear and skin cream, Chinese brands are putting pressure on global rivals that depend on the country for much of their growth. While increasing nationalism has boosted the momentum of domestic products for the past couple of years, the Covid-19 is hastening the shift. With prices typically lower than foreign brands’, domestic products have increasing appeal in times of constrained household budgets, and the growth of online sales has weakened the multinationals’ advantages in distribution and marketing. “Chinese shoppers are showing stronger confidence in local brands,” says Helen Wong of , which has backed local startups such as lingerie maker Neiwai and cafe chain Coffee Box. “The coronavirus is accelerating the trend as people stay home, watch livestreaming, and shop.”

Investors have piled into domestic companies that are overtaking multinational rivals, doubling the combined value of China’s 500 top brands in the past four years to about $3.8 trillion, according to marketing consultancy World Brand Lab. Clothing and shoe manufacturer Anta Sports Products, which in 2018 passed to become China’s No. 2 sports apparel brand behind , is up more than 50% this year even as the benchmark Hang Seng index has fallen 6%. Shares of China’s biggest bottled water brand, , have more than doubled since its September Hong Kong trading debut. , owner of cosmetics house Perfect Diary, a growing threat to the likes ofand , has jumped 75% since its U.S. initial public offering in November.

Local names account for seven of the top 10 cosmetics brands, up from just three in 2017, according to market researcher Daxue Consulting. L’Oréal SA’s Maybelline makeup line has seen its share in China plunge, to 9.1% last year from more than 20% in 2010, according to Euromonitor International. In the skin care and lotion category, the share of L’Oréal Paris dropped, to 4.5% last year from 5.6% in 2014, putting it neck and neck with local brand . The growing strength of Chinese cosmetics makers can be traced to their smart online strategy, according to Derek Deng, a partner in Shanghai with Bain & Co. “Insurgent Chinese brands are more likely to be digital from Day One,” he says, while multinationals tend to favor physical stores.

Perfect Diary, launched in 2017, now stands just behind several European-owned brands, with 4% of the crowded market for so-called color cosmetics such as lipstick and mascara, Euromonitor estimates. Its advertising stresses that its products come from the same manufacturers as Dior, Lancôme, and Armani but sell for less than one-third the price. It’s teamed with ’s Oreos for a skin foundation cream (no, it doesn’t contain ground-up cookies; the box looks like an Oreo). On Singles Day, the Nov. 11 organized by , Perfect Diary’s online store included livestreams of influencers pitching products such as animal-themed eye shadow (co-branded with the Discovery Channel) featuring colors and packaging inspired by rabbits, deer, and fish. “We’ve proven we can stand out in a highly competitive market,” says David Huang, chief executive officer of Yatsen.

Foreign brands aren’t finished in China, of course. They dominate categories such as high-end handbags and luxury cars. Estée Lauder Cos. sold more than 2 billion yuan ($300 million) of products on Singles Day with a livestreaming campaign, two-for-one discounts, and installment payment plans. And —still the biggest fast-food chain in China—is supplementing its fried chicken with products such as fast-cooking stinky sour snail noodles to cater to diners stuck at home in the pandemic. “The attitude of big international brands is changing significantly,” says Wu Wenmi, founder of Wenzihui MCN, an agency in Hangzhou that partners with Alibaba. “They are more humble now and willing to hear our opinions of how to play the game.”

One way Chinese companies are playing the game is with marketing that resonates for locals. While foreigners’ ads stress the nutritional value of their infant formula, Feihe nurtures relationships with consumers via loyalty programs, new-parent support groups, and collections of bedtime stories. And Chinese brands are increasingly tailoring their wares to domestic tastes. , for instance, is stepping up sales of innovations such as pineapple-flavored cheese and squid-infused snacks in addition to its lineup of basic milk and fruit yogurts. “Foreign brands were so innovative three decades ago when they first came to China,” Mengniu CEO Lu Minfang said at a November media briefing. “But now they’re developing slower than local brands.” —Bruce Einhorn and Daniela Wei

That is also the case for China. Debt this year was up bigly. But the USA printing machine went to stocks and paycheck for people, Chinese to infrastructure, and industry.

This Pettis guy is not telling the whole story, only cherry picking the parts that fit his agenda.

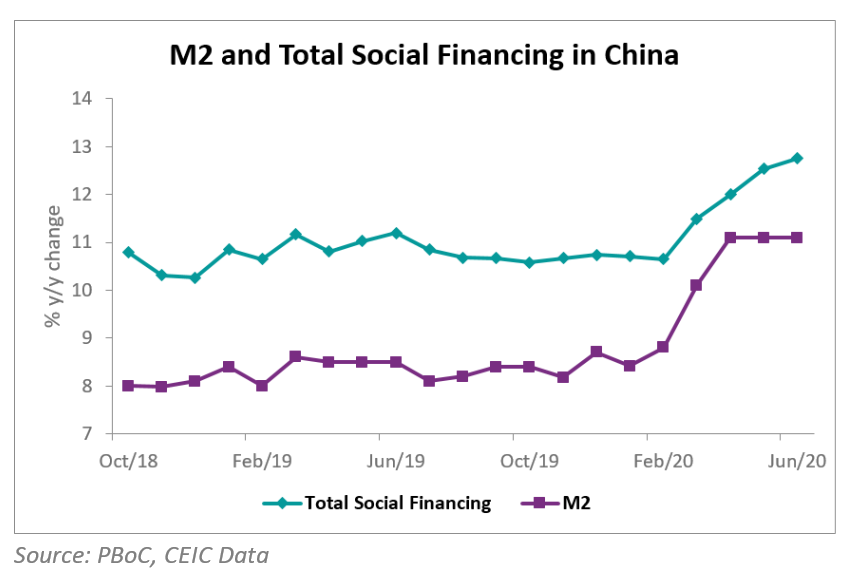

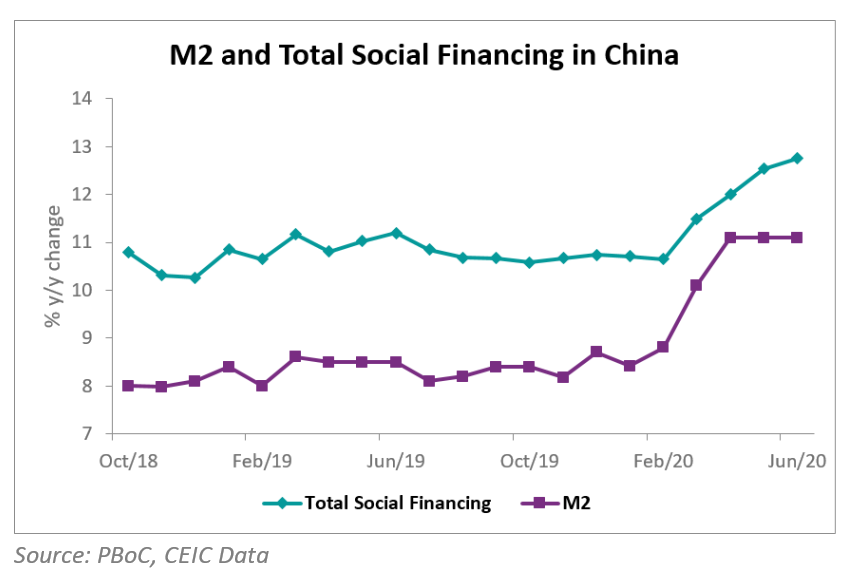

The composition of what made up that total social financing is as important as its size. More fiscal accountabilities are built in there. It has far greater quality than previous stimulus. Plus, SOE's are far stronger and more resilient this time around. It's not a growth of shadow banking sector. China 2020 Covid stimulus up to date amounts to 32% of GDP, still less than 2008 stimulus percentage wise. It's the right size and timing to cushion the Covid shutdowns around the world and in China to kick start the economic engine, and everybody knows the results.