You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

China Ballistic Missiles and Nuclear Arms Thread

- Thread starter peace_lover

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Thank God we still have arm control nerds to downplay nuclear buildup.

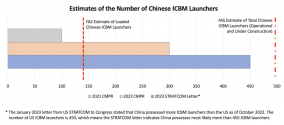

| 2021 FAS estimation | 2023 FAS estimation | STRATCOM estimation | FAS terminal estimation | My estimation | |

| ICBM Launcher count | 116 | 140 | >450 | 490 | 210 now and around 600 at terminal procurement |

First of all FAS is still assuming that each TEL brigade has only 6 launchers and there was 15±1 brigades around there in their 2021 nuclear notebook. Well everyone knows it is simply not true and Pentagon has already rise the bar to 12 launchers per brigade.

Even we take their assumption as baseline here, what FAS is saying is that China only deploy 24 more launchers since 2021. Then what if I told you that North Korea has deployed more than 12 Hwasong-17 since 2020 and not mentioning at least 3 flight attempts during these time.

Let's take a glance at the real production capacity here.

水压工序上大家通力合作,相互配合,经常通宵达旦,全面完成工厂各产品的水压、应变及爆破工作。在两名党员的带领下,水压组持续奋战创下某大型壳体一周产出8台的高产出量。

先锋队每位党员认真履行承诺,知难而进,在技术创新、加工工艺方法优化等方面多点突破,成功打通了生产瓶颈,解决了难题堵点。

在院某重点产品产能提升过程中,党员先锋队亮身份树旗帜,开启了“6+1”、“白+黑”生产模式,积极践行“四个敢于”的企业精神,用行动为周围群众做出表率,起到了良好带动作用。

在开展的“壳体一键式车加工”的攻关中,面对设备资源有限、壳体易变形等难题,先锋队员坚持创新引领,分析车加工技术难点,摸索加工变形规律,优化加工程序和切削参数,采用主程序和子程序调用循环结合方式,分两个层次安排加工程序,实现了产品一键启动加工,加工过程中无需进行测量,改变了以前必须边干边量、边量边干的工作模式,壳体产能较原来提高了4倍,产品质量更加稳定可靠

In a report from August 2022, the factory said that they made a record output of 8 large shells that week. They were working 7/24 to increase production capability and shell production rate has increased in four fold. Ofc it could be a lucky week and should not be taken as baseline estimation.

We assume that normal production rate is 4 shells per week. China has 250 working days/50 working weeks per year though they are likely working in three shifts with no weekends but we take the conservative estimation here. They could produce 200 shells in theory and each ICBM is made of three solid stages so around 60 ICBMs per year.

全面完成2021年科研生产任务 大直径壳体实现产能翻番

在2021年总任务较2020年增长65%的情况下,全厂广大干部职工在厂党委的坚强领导下,秉承“四个敢于”的企业精神,紧密围绕集团公司“建设世界一流航天企业,支撑世界一流军队建设”总目标,以价值创造为导向,科学统筹规划、合理配置资源、创新生产组织与管理,破瓶颈、通堵点、顺流程,积极践行“第一次把正确的事情做正确”的质量管理理念,努力做到工作一流、过程一流、结果一流。工厂在推动企业管理水平上台阶过程中,不仅全面完成了2021年科研生产任务,实现了压力测试2.0总目标,更实现了大型壳体产能翻番的目标,创下历史上最好纪录,为企业高质量发展和后续科研生产任务的顺利推进奠定了坚实基础。

In their 2021 summary, the factory said that the mission load increased by 65% in 2021 and large shell production rate was doubled compared with 2020. Well, the background picture indeed looks like a large shell for ICBM as it is much taller than an adult male.

型号产出能力再创历史新高

统筹资源,科学排产,优化流程,减少冗余,严格过程管控,紧盯上下工序输入输出,认真分析与规划,2米级大型壳体月产出创下公司历史上战略型号月产最高纪录。

In their 2022 summary, the factory once again said that 2m-class large shell set a historical record in production rate for strategic engines.

It is really weird that factory keeps saying they are making records over and over again meanwhile OSINT claims China is a 200% North Korea in ICBM production.

Yes, I agree.Have the technology and almost certainly stored somewhere in the country, but officially not in service for obvious reasons, high precision conventional weapons do the same job and much much safer in terms of escalation.

Though, I was confused because there are claims that China only has "city-killer" strategic nuclear warheads.

I was thinking that in case the US deploys tactical nuclear warheads against Chinese military targets (i.e. warships and bases) in war, China could respond in kind with her own tactical nuclear warheads against US and allied military bases in the WestPac without having to directly resort to strategic nuclear warheads.

Having this capability means that China can tell the US: "You think that only you have tactical nukes and I don't?? Here, taste my tactical nukes as well!! Let me warn you that you better stop right there and pull back before I escalate further with my strategic nukes!!"

But, of course, this would have to depend on how Beijing and Washington DC sees each other's moves on their respective nuclear arsenal deployment. Communication would have to remain open between both countries through the embassies of a third, neutral country to do so, in my opinion.

Nope, wrong solution to the issue because it is stupid to follow your enemies’ escalation ladder. The whole purpose of having nukes is to discourage your enemies from using them on you.Yes, I agree.

Though, I was confused because there are claims that China only has "city-killer" strategic nuclear warheads.

I was thinking that in case the US deploys tactical nuclear warheads against Chinese military targets (i.e. warships and bases) in war, China could respond in kind with her own tactical nuclear warheads against US and allied military bases in the WestPac without having to directly resort to strategic nuclear warheads.

Having this capability means that China can tell the US: "You think that only you have tactical nukes and I don't?? Here, taste my tactical nukes as well!! Let me warn you that you better stop right there and pull back before I escalate further with my strategic nukes!!"

But, of course, this would have to depend on how Beijing and Washington DC sees each other's moves on their respective nuclear arsenal deployment. Communication would have to remain open between both countries through the embassies of a third, neutral country to do so, in my opinion.

China should make it clear to the US if they ever use nukes on Chinese forces, China will send a few ”city-busters” to Pearl Harbor and/or Guam.

they are not nerds, they are smart experts and have more information than us. But why they always publish some reports very strange? I think because there are some policies when you talk about china military power:Thank God we still have arm control nerds to downplay nuclear buildup.

2021 FAS estimation 2023 FAS estimation STRATCOM estimation FAS terminal estimation My estimation ICBM Launcher count 116 140 >450 490 210 now and around 600 at terminal procurement

First of all FAS is still assuming that each TEL brigade has only 6 launchers and there was 15±1 brigades around there in their 2021 nuclear notebook. Well everyone knows it is simply not true and Pentagon has already rise the bar to 12 launchers per brigade.

Even we take their assumption as baseline here, what FAS is saying is that China only deploy 24 more launchers since 2021. Then what if I told you that North Korea has deployed more than 12 Hwasong-17 since 2020 and not mentioning at least 3 flight attempts during these time.

Let's take a glance at the real production capacity here.

In a report from August 2022, the factory said that they made a record output of 8 large shells that week. They were working 7/24 to increase production capability and shell production rate has increased in four fold. Ofc it could be a lucky week and should not be taken as baseline estimation.

We assume that normal production rate is 4 shells per week. China has 250 working days/50 working weeks per year though they are likely working in three shifts with no weekends but we take the conservative estimation here. They could produce 200 shells in theory and each ICBM is made of three solid stages so around 60 ICBMs per year.

In their 2021 summary, the factory said that the mission load increased by 65% in 2021 and large shell production rate was doubled compared with 2020. Well, the background picture indeed looks like a large shell for ICBM as it is much taller than an adult male.

In their 2022 summary, the factory once again said that 2m-class large shell set a historical record in production rate for strategic engines.

It is really weird that factory keeps saying they are making records over and over again meanwhile OSINT claims China is a 200% North Korea in ICBM production.

Rule 1, China is a threat

Rule 2, China can be easily defeated

So they can tell the public china have lots of silos, China is a threat, that is rule 1. But they cannot tell the public China already have enough warheads can destroy almost every cities in US. because it conflicts with the rule 2.

DF-26 TELs on transit. 12 wheels and a large circular opening behind the cab...

They look a little bare. These TELs look much nicer driving around loaded:DF-26 TELs on transit. 12 wheels and a large circular opening behind the cab...

China puts phantom space force concept to the test with aim to swamp enemy missile defences

- Chinese military engineers aim to develop tactic that creates a swarm of fake target signals from space

A Chinese military engineering team is working on developing a “phantom space strike”, a new tactic to create fake signals from space to overwhelm an enemy’s missile defences.

A team of Chinese military engineers is developing a “phantom space strike” – a new tactic to overwhelm missile defences by creating a swarm of fake target signals from .

They revealed the project to the public for the first time this month while announcing they had conducted a proof-of-concept computer simulation.

The modelling results were positive and the project would move to the next stage to tackle engineering challenges, the team said in a paper published in the Chinese-language Journal of Electronics and Information Technology on February 10.

In the simulation, a was launched against an enemy protected by a state-of-the-art missile defence system. The missile did not carry a nuclear or conventional warhead.

After reaching an altitude above the atmosphere, the missile released three small spacecraft.

Radio interference instruments on the spacecraft picked up enemy radar network signals and sent back phantom signals making the unarmed missile appear to be a much bigger threat than it really was.

Based on those signals, the simulated enemy forces on the ground then launched an interceptor towards the ghost warhead.

“Generating phantom tracks in space is extremely difficult,” the team wrote.

“We solved one of the major challenges … with a clever design,” wrote the team that was led by Zhao Yanli, a senior engineer with the People’s Liberation Army Unit 63891.

Unit 63891 is a military agency with nearly 3,000 staff based in Luoyang in the central Chinese province of Henan. It develops and tests , according to openly available information.

Faking an attack is an old trick in modern aerial combat that can confuse and exhaust the opponent.

PLA Air Force officials, for instance, are believed to have scrambled fighter jets in the 1980s to meet a swarm of invading bombers detected by a radar station, but found just a lone aircraft equipped with electronic warfare equipment.

If several aircraft are involved in the jamming operation, sending manipulated signals to different radar sites operating in different frequencies at the same time, an entire radar network can be fooled.

Playing the same trick in space was not previously thought feasible, according to Zhao’s team. The jamming aircraft must change course from time to time to ensure the signals received by different radar stations appear to come from the same target

Employing these manoeuvres in space is a sophisticated and difficult job, and building highly mobile spacecraft would be very expensive, according to Zhao’s team.

“We tried to find another way,” the scientists said in the paper.

Their solution exploits two weak spots in a global missile defence system.

To detect small objects in space, the missile defence radars must be very powerful and housed in large buildings, structures Zhao said were not difficult to find.

Radars are not perfect machines. When merging data from different radar stations, the command centre had to tolerate a margin of error that could result in some fuzziness in tracking signals, the researchers said.

According to their paper, the jamming spacecraft designed by Zhao’s team would be inexpensive because it did not need engines for propulsion. Their flight direction, speed and formation would be set based on intelligence about the enemy’s fixed radar station sites before launch.

After release from the missile, the distance between these jammers would increase over time and affect the accuracy of the phantom target signals.

The engineers said with careful design they could keep the positioning error between different signal sources to less than half a metre, well within the standard error margin of a military radar, citing the computer simulation results.

The three-spacecraft setting in the simulation was a starting point, according to the researchers who said the technology could easily be scaled up to include many more jamming devices to create a large number of phantom tracks on an enemy’s radar screen.

There is a limit to how many warheads a missile defence system can intercept. Real weapons launched amid or after the phantom strike would therefore encounter much less resistance, according to the study.

A complete missile defence system could also include satellites, warships or even high-altitude balloons.

These mobile platforms can be equipped with other monitoring devices, such as heat sensors and optical telescopes, although it is not clear how jamming spacecraft can dodge or fool these detection methods.

“There are many technical details we do not discuss in this paper,” the team wrote.

A space scientist in Beijing not associated with the phantom force study said such technology could trigger an unwanted nuclear retaliation.

“This phantom space force is never likely to be put to use against a powerful opponent,” said the researcher who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the issue.

But he said that developing the capability could be deemed necessary for China.

“It will serve as a strategic deterrence,” he added.

China has considerably fewer nuclear weapons than the US and Russia, according to the Chinese government.

A significant amount of Chinese defence resources has been invested to develop new technologies to penetrate missile defence, such as hypersonic missiles that can manoeuvre in the atmosphere at more than five times the speed of sound.

link -

- Status

- Not open for further replies.