(Cont)

Suppose rim-driven pumpjet propulsors do pan out for China’s navy. How might commanders use newly elusive boats? First of all, they might afford nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs, known to U.S. submariners as “boomers”) precedence when installing newfangled propulsion hardware. The PLA Navy already operates a sizable fleet of diesel-electric attack subs that

for

purposes. They can make shift until silent-running nuclear-powered attack subs (SSNs) join the fleet. SSNs can wait. By contrast, the navy stands at the brink of fielding its first effective SSBNs.

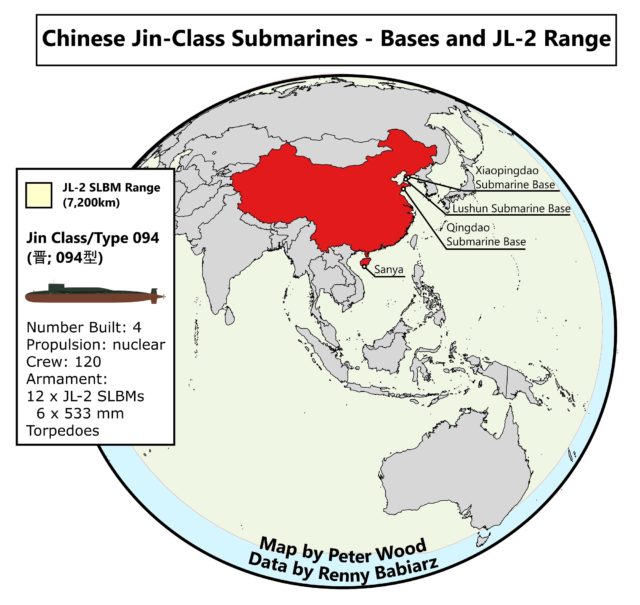

Fabricating a new capability would seem to take precedence over improving an old but adequate one—especially if the nation’s nuclear deterrent depends on the new capability. If this logic prevails, how will the PLA Navy employ working boomers? To all appearances, it envisions employing the South China Sea as an offshore “bastion” for SSBNs, much as the Soviet Navy of yesteryear made semienclosed waters into protected bastions for its missile boats. Undersea deterrence, then, probably numbers among the motives impelling the PLA to transform rocks and atolls into fortified outposts, acquaint itself with underwater hydrography, and so forth. China’s

or their

could slip out of the sub base on Hainan Island, descend into South China Sea waters, lose themselves in the depths and dare rival navies to come into China’s “near seas”—expanses that fall under the shadow of land-based PLA missiles and aircraft—to hunt them.

Or if Chinese Communist Party leaders feel comfortable granting SSBN skippers the liberty to venture outside the near seas (though that’s a lot of atomic firepower to entrust to a naval officer whose loyalties might prove suspect), the Luzon Strait affords a convenient entryway to the western Pacific. Within the strait lies the Bashi Channel, a deep underwater thoroughfare into the Pacific. The weather between Luzon and the southern tip of Taiwan often works against airborne ASW; subs transiting the channel can conceal their whereabouts by diving beneath

that play tricks with sound. An ultraquiet SSBN, in short, could thrive in South China Sea patrol grounds—and beyond.

Second, PLA Navy commanders doubtless salivate at the prospect of ultraquiet attack boats. They could merge new SSNs—presumably the

under development—into their antiaccess defenses against the U.S. Pacific Fleet. They could package new with old units inventively. For example, they could station a picket line of diesel boats and older

along likely axes of approach from Hawaii or U.S. West Coast seaports. Speedy but quiet Type 095s could act as “skirmishers,” operating forward of the pickets. SSNs could snipe at the Pacific Fleet’s flanks during its westward voyage while scouting for the rest of the fleet, and for shore-based PLA defenders. They could mount piecemeal attacks against the American fleet, or even try to herd it toward the picket line for additional punishment.

PLA commanders thus could use ultramodern platforms to wring new value out of legacy platforms. Such an approach would harness the latest technology while staying true to China’s Maoist tradition of “

.” Active defense—which, as Chinese military folk remind us, remains the “

” of Chinese military strategy decades after Mao Zedong’s demise—envisions luring foes deep into Chinese-held territory. PLA defenders stage tactical actions to weary enemies as they come. They fall on isolated units and try to smash them. Successive small-scale attacks enfeeble enemy forces, setting the stage for decisive battle on Chinese ground.

Think about the options that may become available to Chinese skippers as propulsor technology matures. Diesel boats could act as western Pacific pickets, or congregate in

to concentrate firepower from multiple axes. Relatively noisy Type 093s could act as decoys, distracting American ASW hunters while Type 095s spring ambushes at opportune moments. And on and on. Commanders could combine and recombine forces in limitless ways—in keeping with

.

Call it undersea active defense.

Third, the advent of quiet-running SSNs would let the PLA Navy play submarine-on-submarine games reminiscent of those once played by U.S. and Soviet boats. To date, lacking a peer to U.S. Navy Los Angeles– or Virginia-class SSNs, the PLA Navy has employed its submarine fleet mainly as an antisurface force. It waits offshore for hostile forces to approach, then does its best to pummel them with missiles or torpedoes. American submariners, by contrast, will tell you the best ASW weapon is another submarine. They view hunting subs as their chief contribution to high-seas warfare. Chinese submariners might follow suit if their boats ran quiet enough, and boasted sensors sensitive enough, to make sub-on-sub ASW an option. Or they might incorporate ASW into their operational portfolio while retaining the emphasis on antiship missions.

Either way, PLA submarine operations would take on an intensely offensive hue. No longer would the sub force be a mostly static force lofting antiship missiles toward adversary surface task forces. It would seek out adversary subs as well—and, if successful, project China’s antiaccess defenses into the depths in a serious way for the first time. No longer could the United States’ silent service prowl Asian waters with impunity. Indeed, if both fleets were comparable in stealth, cat-and-mouse games might predominate. This would be a dangerous business. Reaction times would be minimal if boats could only detect and track one another at intimate range. Proximity would magnify the prospect of collisions, accidents of other types, or even inadvertent exchanges of fire. Both navies and their political masters must think ahead about how to manage close-quarters encounters in the deep.

And fourth, the debut of pumpjet-equipped SSNs would empower Beijing to mount a standing presence in faraway recesses of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean for the first time. Diesel boats have ventured into the “

” in recent years, but they must put into port at regular intervals to refuel. This exposes them to detection. SSNs can remain at sea, and

undersea, as long as their food and stores hold out. The crew—not the engineering plant—thus constitutes the limiting factor on a nuclear-powered boat’s at-sea endurance. The Indian Navy has taken notice of PLA Navy forays into India’s home region, and grasps the implications of high-tech Chinese SSNs cruising the Indian Ocean. Indeed, some Indian mariners deem such a presence a

for competition between the two navies.

It can be no accident, then, that there’s an antisubmarine flair to this summer’s

among the Indian Navy, U.S. Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. All three navies dispatched aircraft carriers for maneuvers for the first time. The Japanese flattop

is a euphemistically dubbed “helicopter destroyer” optimized for hunting submarines. What hostile subs may lurk in the Bay of Bengal, where the exercises are underway, apart from China’s? Hider-finder competition, it seems, has come to the Indian Ocean.

Does new engineering technology herald an age of Chinese maritime supremacy? Of course not. Carl von Clausewitz portrays martial strife as constant struggle between “wrestlers” striving to “throw” each other for strategic gain. That goes for acoustic one-upmanship as well. One contender innovates; the other resolves to outdo it. It appears, consequently, that more equal undersea competition lies in store. To prepare for it,

U.S. Navy submariners must learn to think of PLA Navy subs not as prey to be devoured by American predators but as worthy foes, capable of some sub hunting of their own. The silent service must adjust to the new, old reality of peer competition beneath the waves.

The game’s afoot.