It seems like you did not read my post at all when you replied.Imo 076 should stick to its strengths as a amphibious assualt dock first and carrier second. The drone support role should be secondary to its main purpose of deploying armoured assets on to a beachhead. Why would valuable interior space be used to host fighters when there are carriers dedicated to the role?

China does not have global military obligations, it does not need every flat top to be a jack of all trades.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Shenyang next gen combat aircraft (?J-XDS)

- Thread starter Blitzo

- Start date

You are saying that 076 can be modified to also carry 6th gen fighter. I'm questioning the whole premise of even utilising it as anything more than a drone support carrier in the first place.It seems like you did not read my post at all when you replied.

Sure it can be done, I just don't see good reason to.

Something to consider. I estimated about a 2000 km combat radius for Shenyang project if launched off EMAL. This could be an overestimate, but just using this as a starting point.

Based on my expectation that PLA can maintain air superiority in waters within 3000 km of its border and will have adequate ASW protection from improved submarine fleet and naval air wing, I mapped up possible theater of operation from a carrier group operating in Southern end of SCS, Celebes Sea and Andamans. I drew 2000 km radius circles around those spots just to get an idea of how far a J-XX could operate. Depending on how things are going, it's conceivable PLAN carriers could safely operate even further out than this depending on which friendly countries they find in rest of Asia. But you can see that their area of operation is quite humongous.

The other thing to consider is just the future of carrier group air wings.

It dawned on me that PLAN might have quite an advantage over USN by middle of next decade if J-XX joins service by 2035 to 2037 timeframe. I think USN is planning to procure 273 F-35C, so most of its piloted air wing will actually not be stealthy at all. Whereas Chinese carriers by that time will be mostly J-35 with a few J-15 more for specialized roles. If you add J-XX + VLO CCAs to that mix, I would have to assess PLAN carrier group as having advantage in air wing. That may encourage them to operate even further away from border (outside of J-36 operational area).

operational flexibility is always a good thing. They are going to have enough 076 that it will need to serve roles beyond just Taiwan. It's clear based on ShiLao and Xi Yazhou programming that J-35 will be operating off 076 at some point. So I don't see why J-XX would not do it in distant future.You are saying that 076 can be modified to also carry 6th gen fighter. I'm questioning the whole premise of even utilising it as anything more than a drone support carrier in the first place.

Sure it can be done, I just don't see good reason to.

I found a very insightful analysis article about Shenyang's sixth-generation fighter on Zhihu (Chinese version Quora), I'm drop it here for you guys to read.

Can`t use ai on pic,so the translation kinda shit on it.

成飞的六代机与沈飞的六代机有何区别? - Author: aaeeq

Starting the analysis of Shenyang Aircraft Corporation's (Shenfei) sixth-generation fighter, just as Chengdu Aircraft Corporation's (Chengfei) sixth-generation fighter has Chief Designer Yang Wei's thesis as a reference, Shenfei's sixth-generation fighter naturally uses Chief Designer Sun Cong's thesis as a reference.

The main similarities are that both acknowledge the era of sixth-generation fighters requires a system-centric approach to victory and the need for drone cooperation (though the specific implications differ, to be analyzed later). Additionally, generational advancement does not entail complete negation or complete inheritance. Compared to Chengdu's sixth-generation fighter, Chief Designer Sun's argument has some distinctions. Firstly, Chief Designer Sun proposed three assertions. The first is the equal emphasis on capability and scale. The Shenyang sixth-generation fighter requires not only sufficient performance but also adequate numbers to maintain a balance or advantage in quantity, even under conditions of prolonged operations (continuous 24/7 for seven days) and when some nearby airfields are compromised by enemy fire, necessitating long-distance turnaround.

Secondly, there is the trade-off between specialization and multirole capability. From this perspective, Chengdu's assessment of the future air combat scenario leans towards optimism. Chengdu's sixth-generation fighter emphasizes multirole capabilities, pursuing efficiency. In contrast, Shenyang adopts a more cautious approach, believing that the pressure of air combat will be significant, and thus, their sixth-generation fighter leans more towards specialized air combat, focusing on effectiveness. This implies that the roles Chengdu and Shenyang played in the fifth-generation era, represented by the J-20 and J-35, have somewhat swapped in the sixth-generation era. To some extent, during the fifth-generation era, China's air force was purely seeking self-defense as a tactical air force, and Chengdu won the bid. The FC-31/J-35 was later developed and successfully transitioned to fill the multirole demand. In the sixth-generation era, Chengdu anticipates that China will achieve air superiority and evolve into a strategic air force, hence developing a multirole fighter, while Shenyang remains relatively cautious.

The third point is digital engineering and rapid innovation. This can be understood by looking at the F-35 and B-21 programs. Essentially, it involves using digital simulations to accelerate development speed and having a production line (pulse line) that doesn't have a fixed process encapsulation phase, allowing for continuous improvements. These are well-trodden topics, so there's no need to elaborate further.

Moving on to the specifics of aircraft design, Chief Designer Yang Wei uses the term "OODA 3.0/intelligence reigns supreme" to describe his approach, while Chief Designer Sun Cong describes his as "cognitive maneuver air combat/tri-domain integrated maneuver for victory," which encompasses the information domain, cognitive domain, and physical domain.

First, let's discuss the information domain. Chief Designer Sun's thesis delves deeper into the details, whereas Chief Designer Yang's thesis covers a broader range but is relatively more general. Sun provides a more in-depth introduction to the specific practices in each domain. In the realm of the information domain, the assessments of both Chengdu and Shenyang are nearly identical, and one can directly refer to the original text of the theses for this information.

Then, in the physical domain, the differences between Chengdu and Shenyang become more pronounced.

Although both parties acknowledge the value of prolonged supersonic cruising at speeds of 1.5-2 Mach, beyond this, based on the enhanced images of the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter, and assuming that my earlier size estimates are not significantly off, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter features only a double-swept, medium-aspect-ratio flying wing with two sets of split drag rudders at the rear and three sets of conventional trailing-edge flaps as aerodynamic control surfaces. At most, it includes three thrust-vectoring nozzles, with no additional control surfaces, not even leading-edge flaps or vertical tails, and boasts an exceptionally large wing area, likely reaching 220 square meters, which is nearly three times that of the previous generation of fighters. This implies that despite its large takeoff weight, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter may have a lower wing loading than its predecessors. This suggests that, apart from the flying wing's ease in meeting supersonic cruise requirements and the three engines' ease in providing high specific excess power (SEP), there are no other maneuverability requirements. In other words, there may still be some demand for pitch axis maneuverability and, through technical means (circulation control wings to enhance lift differential for roll), roll axis maneuverability, but there is almost no requirement for horizontal turning maneuverability. If horizontal maneuverability is needed, it is substituted with a combination of roll and pitch axis maneuvers. Additionally, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter emphasizes long range, endurance, and sufficient air-to-air/air-to-ground weapon payload, indicating a requirement for large internal weapon bays and substantial internal fuel capacity.

Due to the 8 files limit,to be countiinued in fllowing post.

Can`t use ai on pic,so the translation kinda shit on it.

成飞的六代机与沈飞的六代机有何区别? - Author: aaeeq

Starting the analysis of Shenyang Aircraft Corporation's (Shenfei) sixth-generation fighter, just as Chengdu Aircraft Corporation's (Chengfei) sixth-generation fighter has Chief Designer Yang Wei's thesis as a reference, Shenfei's sixth-generation fighter naturally uses Chief Designer Sun Cong's thesis as a reference.

The main similarities are that both acknowledge the era of sixth-generation fighters requires a system-centric approach to victory and the need for drone cooperation (though the specific implications differ, to be analyzed later). Additionally, generational advancement does not entail complete negation or complete inheritance. Compared to Chengdu's sixth-generation fighter, Chief Designer Sun's argument has some distinctions. Firstly, Chief Designer Sun proposed three assertions. The first is the equal emphasis on capability and scale. The Shenyang sixth-generation fighter requires not only sufficient performance but also adequate numbers to maintain a balance or advantage in quantity, even under conditions of prolonged operations (continuous 24/7 for seven days) and when some nearby airfields are compromised by enemy fire, necessitating long-distance turnaround.

Secondly, there is the trade-off between specialization and multirole capability. From this perspective, Chengdu's assessment of the future air combat scenario leans towards optimism. Chengdu's sixth-generation fighter emphasizes multirole capabilities, pursuing efficiency. In contrast, Shenyang adopts a more cautious approach, believing that the pressure of air combat will be significant, and thus, their sixth-generation fighter leans more towards specialized air combat, focusing on effectiveness. This implies that the roles Chengdu and Shenyang played in the fifth-generation era, represented by the J-20 and J-35, have somewhat swapped in the sixth-generation era. To some extent, during the fifth-generation era, China's air force was purely seeking self-defense as a tactical air force, and Chengdu won the bid. The FC-31/J-35 was later developed and successfully transitioned to fill the multirole demand. In the sixth-generation era, Chengdu anticipates that China will achieve air superiority and evolve into a strategic air force, hence developing a multirole fighter, while Shenyang remains relatively cautious.

The third point is digital engineering and rapid innovation. This can be understood by looking at the F-35 and B-21 programs. Essentially, it involves using digital simulations to accelerate development speed and having a production line (pulse line) that doesn't have a fixed process encapsulation phase, allowing for continuous improvements. These are well-trodden topics, so there's no need to elaborate further.

Moving on to the specifics of aircraft design, Chief Designer Yang Wei uses the term "OODA 3.0/intelligence reigns supreme" to describe his approach, while Chief Designer Sun Cong describes his as "cognitive maneuver air combat/tri-domain integrated maneuver for victory," which encompasses the information domain, cognitive domain, and physical domain.

First, let's discuss the information domain. Chief Designer Sun's thesis delves deeper into the details, whereas Chief Designer Yang's thesis covers a broader range but is relatively more general. Sun provides a more in-depth introduction to the specific practices in each domain. In the realm of the information domain, the assessments of both Chengdu and Shenyang are nearly identical, and one can directly refer to the original text of the theses for this information.

Then, in the physical domain, the differences between Chengdu and Shenyang become more pronounced.

Although both parties acknowledge the value of prolonged supersonic cruising at speeds of 1.5-2 Mach, beyond this, based on the enhanced images of the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter, and assuming that my earlier size estimates are not significantly off, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter features only a double-swept, medium-aspect-ratio flying wing with two sets of split drag rudders at the rear and three sets of conventional trailing-edge flaps as aerodynamic control surfaces. At most, it includes three thrust-vectoring nozzles, with no additional control surfaces, not even leading-edge flaps or vertical tails, and boasts an exceptionally large wing area, likely reaching 220 square meters, which is nearly three times that of the previous generation of fighters. This implies that despite its large takeoff weight, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter may have a lower wing loading than its predecessors. This suggests that, apart from the flying wing's ease in meeting supersonic cruise requirements and the three engines' ease in providing high specific excess power (SEP), there are no other maneuverability requirements. In other words, there may still be some demand for pitch axis maneuverability and, through technical means (circulation control wings to enhance lift differential for roll), roll axis maneuverability, but there is almost no requirement for horizontal turning maneuverability. If horizontal maneuverability is needed, it is substituted with a combination of roll and pitch axis maneuvers. Additionally, the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter emphasizes long range, endurance, and sufficient air-to-air/air-to-ground weapon payload, indicating a requirement for large internal weapon bays and substantial internal fuel capacity.

Due to the 8 files limit,to be countiinued in fllowing post.

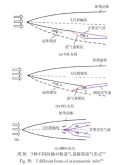

However, the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter is not the same. Before discussing the so-called mission layer and supersonic cruise, it first addresses the need for maneuverability. Therefore, the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter has more requirements in the physical domain than the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter. Of course, the statement that there will be significant changes in the form and energy distribution of offense and defense in the future indicates that there is still some difference from previous eras. Combining with the previous text, it is clear that advantageous maneuvers in the form of attack are no longer pursued, meaning that high altitude and high speed are no longer sought after. High altitude means you are in a position without clutter, while the opponent is under the cover of ground clutter. High speed means providing more acoustic/optical information, leading to a disadvantage in the information domain. The gradual improvement in missile performance also means that the empowerment effect of aircraft maneuverability on missiles is gradually diminishing. On the other hand, there is a significant demand for maneuverability in defensive situations, that is, the pursuit of a comprehensive maneuverability B value, which breaks down into the maximum sustained load factor G sustained, the maximum instantaneous load factor G instantaneous, and the previously mentioned specific excess power SEP. The pursuit of SEP is the same, but the pursuit of load factor maneuverability is somewhat different, with more emphasis on the ability to perform high-load maneuvers while maintaining high-speed supersonic cruise. This can also be understood as a need for supersonic medium-range missile dueling (Chief Designer Sun mentioned that the performance of dogfight missiles has improved too much, making close-range dogfights too risky and unrealistic, almost certainly resulting in a one-for-one exchange, hence the need to win at medium range), or more specifically, maneuvers like the 39-degree dive, Immelmann turn, and Split S.

Currently, a relatively high-definition video has been released, confirming my perspective. The design of the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter is highly similar to the small-aspect-ratio flying wing standard model proposed by China during the 12th Five-Year Plan period. The difference lies in the leading edge being modified to a double-swept angle to enhance performance (the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter also features a double-swept leading edge). The multiple control surfaces distributed at different positions ensure that the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter has a high load capacity even at high speeds. Of course, this also implies that the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter is estimated to be relatively light, at least much lighter than the Chengdu sixth-generation fighter, allowing a twin-engine configuration to ensure a high specific excess power (SEP). Additionally, although Chief Designer Sun's thesis also acknowledges the requirements for long range and endurance, there is a significant difference from Chengdu's approach: Shenyang believes that this issue should not be solved by the aircraft itself but by a more advanced next-generation refueling support system, especially an aerial refueling system (including fighter-to-fighter refueling, a combination of unmanned stealth tankers and manned large tankers), to ensure that maneuverability is not compromised.

From this perspective, I also have a somewhat speculative personal guess regarding the V-shaped notch that runs from the middle of the intake through the entire weapon bay and the middle of the engine to the tail cone of the Shenyang sixth-generation fighter. I believe this is likely an optimized central lifting body designed for high-speed performance. Traditional central lifting bodies use boundary layers to increase lift, which is effective at low speeds but less so at high speeds. Additionally, designs like the Su-57 have certain negative impacts on weapon bay deployment and can create low-pressure zones at the tail, increasing drag and imposing requirements on tail cone design, while also forming many 90-degree dihedral angle reflections that affect stealth. This new V-notch central lifting body, similar to a wedge-derived waverider, could use shock wave principles to enhance lift, performing better at high speeds and more efficiently introducing airflow to the rear to solve low-pressure zone issues. The smaller notch could also avoid affecting weapon bay deployment, and since the angle is not 90 degrees, the impact on stealth would be smaller and within acceptable limits. Of course, this is just my personal speculation and lacks definitive evidence to prove it.

to be...

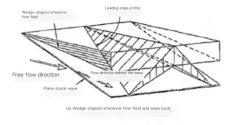

Then there is the cognitive domain, where the differences between Chengdu and Shenyang are also quite significant. Specifically, the so-called cognitive domain refers to the understanding of the sixth-generation fighter system. If Chief Designer Yang's thesis focuses on how to build their own sixth-generation fighter system and establish their own OODA 3.0 combat cycle, emphasizing "you fight your way, I fight mine," Shenyang's logic is about how to identify and understand the opponent's system, prevent the opponent from identifying and understanding their own system, thereby gaining an advantage in cognitive confrontation, and then disrupt the opponent's system cycle to achieve victory. This approach emphasizes knowing both yourself and your enemy to win every battle, which is quite different.

At the same time, the cooperation between drones and manned aircraft is also a key point. Although both emphasize the role of drones, there are significant differences in their specific approaches. Shenyang's description is not only more detailed but also more cautious. They not only conducted a thought experiment using the system the US military is trying to build but also reflected their specific construction ideas for the cooperation between drones and manned aircraft.

They also proposed that in complex electromagnetic environments, drones should enhance their AI capabilities and possess better autonomous decision-making abilities. Humans only need to set the general direction in advance, and the drones will mainly execute tasks autonomously. This is quite different from Chengdu's approach. Chengdu emphasizes the direct integration of AI with humans to form a combat brain, reducing the burden on the pilot, while not overly demanding the physical domain performance of the aircraft. This allows the pilot to directly supervise or control the drones. In contrast, Shenyang believes that in the future, in complex electromagnetic environments, it will be difficult for any party to maintain stable communication, even over short distances. Additionally, since the pilot needs to allocate attention to the physical domain's maneuvering behaviors and has not abandoned this aspect, there is a need to strengthen the autonomous decision-making capabilities of drones. This represents a significant difference in the approaches of the two.

to be...

Attachments

Last edited:

operational flexibility is always a good thing. They are going to have enough 076 that it will need to serve roles beyond just Taiwan. It's clear based on ShiLao and Xi Yazhou programming that J-35 will be operating off 076 at some point. So I don't see why J-XX would not do it in distant future.

Guys - maybe @Blitzo has a different opinion - but we have barely a handful of images, not much enough facts at hand to even closely guess the dimensions or even performance, we still do not fully understand this "thing" and you are already discussing operational aspects off the 076!??

Can we stop this at least here in this thread?

Finally, this is Chief Designer Sun's summary description, further emphasizing the core of the cognitive maneuver air combat he proposed, which is to disrupt the opponent's cycle and achieve victory by knowing both yourself and your enemy. It can be said that these two theses are excellently reflected in the sixth-generation prototype aircraft of both companies, and one can clearly feel the high degree of consistency with the theses. Comparing them can greatly enhance one's understanding. That's all.

Transtlate:

After more than a century of air combat practice, humanity has experienced two eras of air combat: energy maneuver victory and information maneuver victory. With the rapid development of autonomous and artificial intelligence technologies, among other incremental and variable technologies, future air combat will quickly enter the era of cognitive maneuver victory. The confrontation between complex air combat systems, characterized by the collaboration of manned and unmanned systems, will be the primary mode of future air combat. The core pursuit of cognitive maneuver air combat is to identify and understand the relationships between multiple nodes, the system architecture, and the complex kill chains of the opponent, while preventing the opponent from identifying and understanding our own system architecture and kill chains. It seeks to delay, disrupt, and interrupt the opponent's closed-loop functions across the entire kill chain. Based on the demands of great power competition and the era of great power rivalry, the mission positioning under the concept of future joint operations, and the technological transformations of the digital age, the next-generation fighter will undoubtedly be a core backbone node in the equipment structure, focusing on air superiority and scalability, capable of rapid response at the mission level, and winning cognitive maneuver air combat at the engagement level within a complex air combat system.

Strategic superiority vs tactical superiority thinking.View attachment 142736

Finally, this is Chief Designer Sun's summary description, further emphasizing the core of the cognitive maneuver air combat he proposed, which is to disrupt the opponent's cycle and achieve victory by knowing both yourself and your enemy. It can be said that these two theses are excellently reflected in the sixth-generation prototype aircraft of both companies, and one can clearly feel the high degree of consistency with the theses. Comparing them can greatly enhance one's understanding. That's all.

View attachment 142737