On Friday, U.S. President Donald Trump wrote in a tweet that he wanted 5G and 6G technology in the United States. He later said that he wanted the U.S. to "win through competition, not by blocking out currently more advanced technologies."

When a Chinese reporter asked if this list included Huawei, the answer was surprisingly open. Trump said that means all companies.

This is a marked contrast from Trump's previous tone on the company. In December, he considered signing an executive order banning Huawei from selling equipment in the U.S., citing national security as a reason to bar U.S. companies from using telecommunications equipment made by Huawei.

However, he has not signed that order yet.

When meeting with Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, Trump said he is thinking of holding off on signing the order.

In this case, does this mean that the Trump administration has changed its tone on the Chinese telecoms company?

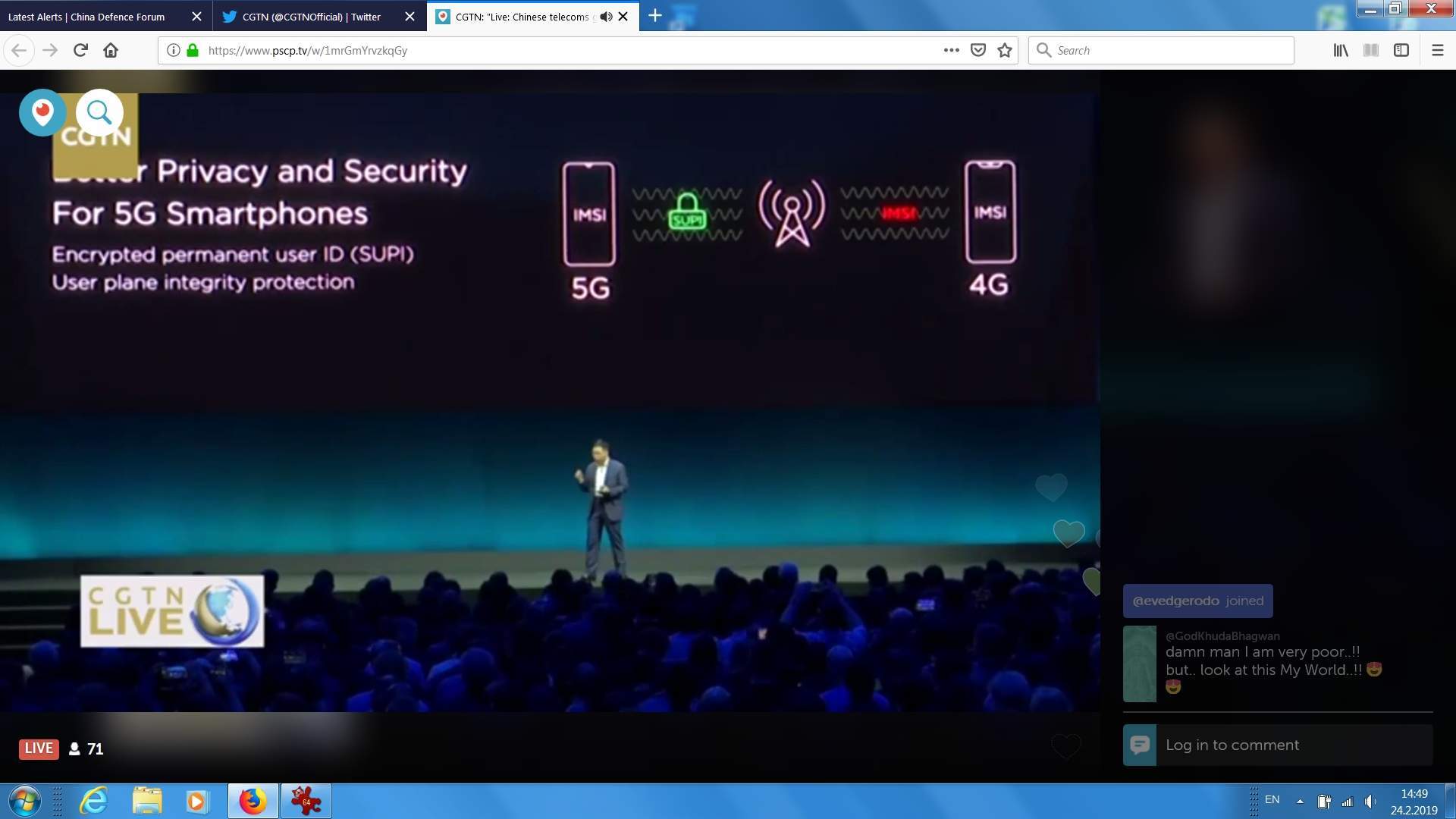

Perhaps not. Speaking to Fox Business on Thursday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that countries using Huawei equipment will no longer be provided top-secret intelligence by the U.S., as they cannot keep confidential information hush-hush.

However, Trump's words did send out positive signals, and if interpreted in light of the ongoing talks in Washington, Trump is perhaps eyeing strategic gains by softening his position. Yet, is that to say that the hawkish China policy will change and Beijing should let its guard down?

Arguably negative. As some analysts have noted, if the Cabinet keeps pursuing its antagonistic approach, the combative policy against China is most likely to stay put. After all, policy is not made solely by Trump himself but heavily shaped by his hawkish staff members. So, how much can Trump do to help Huawei if he really thinks otherwise?

This lies in how we understand the president's power. Those unfamiliar with U.S. politics would assume that everything from disaster relief to trade negotiations, falls within the purview of the president, and everyone within the White House. Nevertheless, as the New York Times unveiled, there really is resistance against Trump within the Cabinet, and divergence is not uncommon.

Under the American Constitution, it is largely a misconception that the president can unleash "shock and awe" on his own initiatives. In a mechanism envisioned by the framers of the Constitution, executive powers should be checked if not dwarfed by the legislative branch, which makes laws, while the president is empowered only to execute them.

For better or for worse, the essence of a republic requires that deliberate democracy be put higher on the political agenda, which enables careful debate for both popular will and elite limits on what will to be reflected. Therefore, presidential power grabs have often been followed by congressional backlash, and in theory, the president can only do so much.

That is to say, decades have witnessed a secret transformation of the country's executive powers. This is on one hand, prompted by the tremendous complexity of the modern society, and on the other hand, by the growing concern over national security and economy.

In the 20th century for instance, the Great Depression propelled the presidency to a level of dominance, and the 9/11 attacks further extended presidential power to new heights.

In an era of Trump, the expansion of presidential power has been even more unparalleled, and this is nowhere better seen than in a cumulative number of executive orders Trump has signed, which increased month by month since 2017 and reached 95 by February 2019.

Most astonishingly, Trump's first stab at the so-called travel ban and his recent invocation of presidential emergency powers to get his wall built all adds up to an impression that Trump has gone so far by taking advantage of the Constitution and strengthening his own authority.

In this light, with such unleashed presidential prerogatives in hand, Trump can indeed ease the current Huawei plight. To the very least, he may pause the executive order banning Huawei from selling equipment in the U.S.

But whether he will wield that power depends on how well the extended trade talk goes. For the moment, as Secretary of Commerce Ross said, it's a little early for champagne.