You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

CV-16 Liaoning (001 carrier) Thread II ...News, Views and operations

- Thread starter Jeff Head

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

If I was concern about the leakage then I would have higher pressure on the secondary loop .So if there is leakage the flow goes into the primary loop and not the other way around

Because the containment unit it uninhabited whereas the Turbine room is close to control room and not contain meaning the air can leak outside.

The temperature in the secondary loop to the turbine has to be lower than in the primary loop from the reactor. Otherwise heat exchange between the loops would go in the wrong direction. The fact that steam temperature in the secondary loop is capped at the temperature in the primary loop puts limit on the pressure in the secondary loop. Making the steam wet is just a way of getting the most pressure out of the same limited temperature.

It would be fantastic to see some high speed turns. Ones a boat would make to void torpedoes.

asif iqbal

Banned Idiot

Looks good

Now like see Type 901 AOR alongside

Now like see Type 901 AOR alongside

Hendrik_2000

Lieutenant General

The temperature in the secondary loop to the turbine has to be lower than in the primary loop from the reactor. Otherwise heat exchange between the loops would go in the wrong direction. The fact that steam temperature in the secondary loop is capped at the temperature in the primary loop puts limit on the pressure in the secondary loop. Making the steam wet is just a way of getting the most pressure out of the same limited temperature.

But the primary loop is maintain at liquid form all the time only the secondary loop generate steam So all you have to do is maintain pressure just above the saturated pressure of water at that temperature and that pressure is supplied by the pressurizer in the primary loop

But your argument make sense since the saturated pressures of higher temp primary loop need to be higher than the lower temp of secondary loop

But that make it PWR inherently unsafe because any leak will be directed toward the non containment part of power plant

I never thought about it

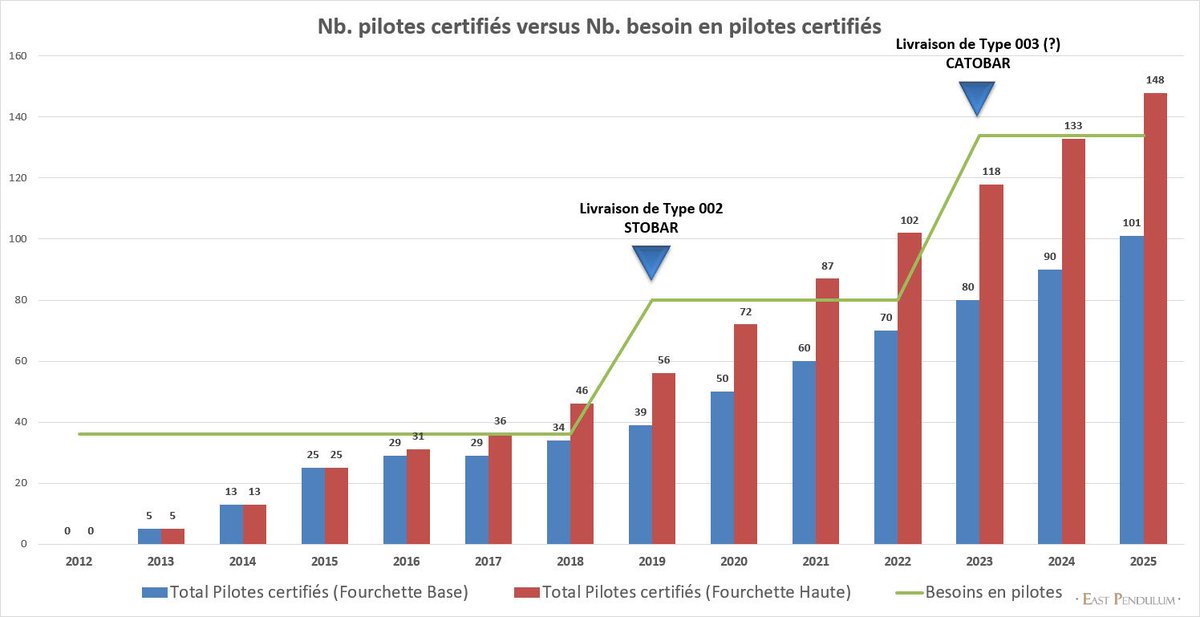

No news from the recent outing of Liaoning but Henri K guess they graduate new batch of pilot

If my analysis is correct, the 7th Naval Training Promotion includes six new pilots and two LSOs, in line with the previous six waves. The number of J-15 pilots is therefore sufficient, but not that of the aircraft, for the Liaoning aircraft carrier to be complete.

This is my first post here so hello all...

Enlisting your expert help here - how reliable is this article?

Enlisting your expert help here - how reliable is this article?

Why the humble jellyfish could stop China’s aircraft carriers in their tracks

Scientists testing ‘jellyfish shredder’ to reduce risk of their systems becoming clogged up by animals sucked into their pipes

PUBLISHED : Monday, 27 November, 2017, 11:03pm

UPDATED : Tuesday, 28 November, 2017, 9:09am

27 Nov 2017

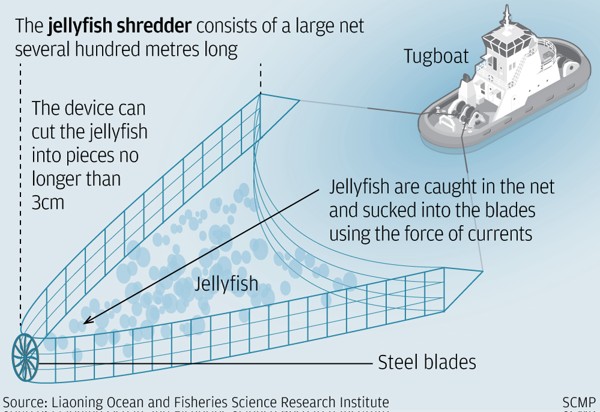

China is testing a new weapon to counter a major threat to aircraft carriers: jellyfish.

Dubbed the “jellyfish shredder”, the instrument can clear a passage in water infested by jellyfish to give the carrier crew “peace of mind”, according to a scientist involved in recent field tests.

The researcher, from the Liaoning Ocean and Fisheries Science Research Institute based in Dalian, northeast China, requested not to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue.

Tan Yehui, a researcher with the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Guangzhou, said jellyfish posed a serious threat to aircraft carriers given the size and complexity of the warships.

A large number of the invertebrates can get sucked into a ship’s water intake mouth and clog up the cooling system. This in turn can cause the carrier’s engines to overheat, bringing them to a halt.

It can take hours, or even days, to remove the sticky remains of the jellyfish from filters and pipes.

China’s first aircraft carrier the Liaoning – originally a Soviet vessel – was rebuilt in Dalian.

It is believed three more carriers are under construction at the strategic port in Bohai Bay, as China rapidly expands its naval power to protect its business and political interests around the globe.

Although warships already have measures in place to combat the jellyfish threat, encountering large numbers of them at once can still cause problems.

In 2006, America’s nuclear-powered supercarrier USS Ronald Reagan was temporarily disabled after running into a swarm of jellyfish in the waters outside the Australian port of Brisbane.

“What happened to the American aircraft carrier can also happen to Chinese aircraft carriers,” said Tan, who was not directly involved in the Liaoning tests.

The jellyfish shredder takes the form of a large net several hundred metres long with a cluster of sharp steel blades in the middle.

The net is towed by a boat travelling at high speeds, using the force of the rapid currents to suck the jellyfish into the blades.

According to a paper published by the project team in the journal Hebei Fisheries in August, the device cuts the jellyfish into small pieces no longer than 3cm – about a tenth of the size of an adult jellyfish commonly seen in Chinese waters.

The waters become murky about a day after the operation as the fragmented corpses start to decompose.

Organic pollutants – measured by oxygen levels – peak four days after the operation, but the waters clear after a week when the remnants have completely dissolved, according to the team’s experiments.

However, the researchers warned that the method could cause environmental problems.

The severed tentacles, for instance, can be washed onto beaches and risk stinging bathers.

Skin contact with jellyfish venom can cause intense pain, inflammation or even death.

If the shredder catches pregnant jellyfish it could also release a mass of fertilised eggs, which would produce more outbreaks in the next season.

The Dalian team also tested other methods to reduce jellyfish numbers. In one experiment they pumped air into the ocean to create a large number of bubbles, which lift the jellyfish to the surface where they can be killed with pesticides.

However, Tan questioned the effectiveness of these methods, saying the shredder could only catch relatively large jellyfish.

In recent years many outbreaks in China’s coastal waters have been caused by smaller species with an average length of no more than 2cm.

Tan also warned that both shredding and pesticides would kill other marine creatures, a point conceded by the testing team.

She said the aircraft carrier fleet should consider setting up a jellyfish forecast system to plan their operations in the interval between outbreaks.

China and many other countries have recorded jellyfish outbreaks of an unprecedented scale and frequency in recent decades.

Swarms of the creatures have caused beaches to shut down, caused salmon stocks to disappear and, echoing the problems they pose to aircraft carriers, clogged up nuclear power plants.

While the reasons for these outbreaks vary, many marine biologists believe that rising sea temperatures caused by global climate change have provided warm beds that aid jellyfish reproduction.

“The outbreak often occurs in waters with the right temperature and salinity. These elements should be monitored, predicted and avoided by naval operations,” Tan said.

There are other factors that may exacerbate the problem in Chinese waters.

One researcher at the Institute of Oceanology in Qingdao argued the pollution in the seas around China were providing food to microorganisms such as algae, which in turn has led to an increase in the number of jellyfish that prey on them.

But some researchers, including Tan, argue that jellyfish cannot survive in heavily polluted waters.

Instead they blame overfishing, which has led to a reduction, or even the extinction, of species that prey on jellyfish.

I remember reading some years ago that a coastal power station (where?) was disabled for several days because it had sucked up a fleet of jellyfish.This is my first post here so hello all...

Enlisting your expert help here - how reliable is this article?

The amount of fish in the seas is much less than it was two centuries ago. After both World Wars the fishing in the North Sea was for several years much better than before the wars so even a few years reduced fishing had a noticeable effect.

Excellent picture of the hangar deck, showing the division into three areas, with the blast/fire walls that can be pulled across to retard the spread of fire and danger associated with the ability for fires and such angers to spread.

This is a decent article. Such swarms are known to the US Navy..and any navy for that matter that has any large or extended presence at sea.This is my first post here so hello all...

Enlisting your expert help here - how reliable is this article?

...and they can be debilitating if you are unfortunate to run into them. Once a swarm is identified they attempt to spot it and track it so as to be able to avoid it if they can.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.