In the uncertain years after Mao’s death, long before China became an industrial juggernaut, before the Communist Party went on a winning streak that would reshape the world, a group of economics students gathered at a mountain retreat outside Shanghai. There, in the bamboo forests of Moganshan, the young scholars grappled with a pressing question: How could China catch up with the West?

It was the autumn of 1984, and on the other side of the world, Ronald Reagan was promising “morning again in America.” China, meanwhile, was just recovering from decades of political and economic turmoil. There had been progress in the countryside, but more than still lived in extreme poverty. The state decided where everyone worked, what every factory made and how much everything cost.

The students and researchers attending the Academic Symposium of Middle-Aged and Young Economists wanted to unleash market forces but worried about crashing the economy — and alarming the party bureaucrats and ideologues who controlled it.

Late one night, they reached a consensus: Factories should meet state quotas but sell anything extra they made at any price they chose. It was a clever, quietly radical proposal to undercut the planned economy — and it intrigued a young party official in the room who had no background in economics. “As they were discussing the problem, I didn’t say anything at all,” recalled Xu Jing’an, now 76 and retired. “I was thinking, how do we make this work?”

The Chinese economy has grown so fast for so long now that it is easy to forget how unlikely its metamorphosis into a global powerhouse was, how much of its ascent was improvised and born of desperation. The proposal that Mr. Xu took from the mountain retreat, soon adopted as government policy, was a pivotal early step in this astounding transformation.

China now leads the world in the number of homeowners, internet users, college graduates and, by some counts, billionaires. Extreme poverty has fallen to less than 1 percent. An isolated, impoverished backwater has evolved into the most significant rival to the United States since the fall of the Soviet Union.

An epochal contest is underway. With President Xi Jinping pushing a more assertive agenda overseas and tightening controls at home, the Trump administration has launched a trade war and is gearing up for what could be a new Cold War. Meanwhile, in Beijing the question these days is less how to catch up with the West than how to pull ahead — and how to do so in a new era of American hostility.

The pattern is familiar to historians, a rising power challenging an established one, with a familiar complication: For decades, the United States encouraged and aided China’s rise, working with its leaders and its people to build the most important economic partnership in the world, one that has lifted both nations.

During this time, eight American presidents assumed, or hoped, that China would eventually bend to what were considered the established rules of modernization: Prosperity would fuel popular demands for political freedom and bring China into the fold of democratic nations. Or the Chinese economy would falter under the weight of authoritarian rule and bureaucratic rot.

But neither happened. Instead, China’s Communist leaders have defied expectations again and again. They embraced capitalism even as they continued to call themselves Marxists. They used repression to maintain power but without stifling entrepreneurship or innovation. Surrounded by foes and rivals, they avoided war, with one brief exception, even as they fanned nationalist sentiment at home. And they presided over 40 years of uninterrupted growth, often with unorthodox policies the textbooks said would fail.

In late September, the People’s Republic of China marked a milestone, surpassing the Soviet Union in longevity. Days later, it celebrated a record 69 years of Communist rule. And China may be just hitting its stride — a new superpower with an economy on track to become not just the world’s largest but, quite soon, the largest by a wide margin.

The world thought it could change China, and in many ways it has. But China’s success has been so spectacular that it has just as often changed the world — and the American understanding of how the world works.

There is no simple explanation for how China’s leaders pulled this off. There was foresight and luck, skill and violent resolve, but perhaps most important was the fear — a sense of crisis among Mao’s successors that they never shook, and that intensified after the Tiananmen Square massacre and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Even as they put the disasters of Mao’s rule behind them, China’s Communists studied and obsessed over the fate of their old ideological allies in Moscow, determined to learn from their mistakes. They drew two lessons: The party needed to embrace “reform” to survive — but “reform” must never include democratization.

China has veered between these competing impulses ever since, between opening up and clamping down, between experimenting with change and resisting it, always pulling back before going too far in either direction for fear of running aground.

Many people said that the party would fail, that this tension between openness and repression would be too much for a nation as big as China to sustain. But it may be precisely why China soared.

Whether it can continue to do so with the United States trying to stop it is another question entirely.

Apparatchiks Into Capitalists

None of the participants at the Moganshan conference could have predicted how China would take off, much less the roles they would play in the boom ahead. They had come of age in an era of tumult, almost entirely isolated from the rest of the world, with little to prepare them for the challenge they faced. To succeed, the party had to both reinvent its ideology and reprogram its best and brightest to carry it out.

Mr. Xu, for example, had graduated with a degree in journalism on the eve of Mao’s violent Cultural Revolution, during which millions of people were purged, persecuted and killed. He spent those years at a “cadre school” doing manual labor and teaching Marxism in an army unit. After Mao’s death, he was assigned to a state research institute tasked with fixing the economy. His first job was figuring out how to give factories more power to make decisions, a subject he knew almost nothing about. Yet he went on to a distinguished career as an economic policymaker, helping launch China’s first stock market in Shenzhen.

Among the other young participants in Moganshan were Zhou Xiaochuan, who would later lead China’s central bank for 15 years; Lou Jiwei, who ran China’s sovereign wealth fund and recently stepped down as finance minister; and an agricultural policy specialist named Wang Qishan, who rose higher than any of them.

Mr. Wang headed China’s first investment bank and helped steer the nation through the Asian financial crisis. As Beijing’s mayor, he hosted the 2008 Olympics. Then he oversaw the party’s recent high-stakes crackdown on corruption. Now he is China’s vice president, second in authority only to Xi Jinping, the party’s leader.

The careers of these men from Moganshan highlight an important aspect of China’s success: It turned its apparatchiks into capitalists.

Bureaucrats who were once obstacles to growth became engines of growth. Officials devoted to class warfare and price controls began chasing investment and promoting private enterprise. Every day now, the leader of a Chinese district, city or province makes a pitch like the one Yan Chaojun made at a business forum in September.

“Sanya,” Mr. Yan said, referring to the southern resort town he leads, “must be for businesses, and welcome investment from foreign companies.”

It was a remarkable act of reinvention, one that eluded the Soviets. In both China and the Soviet Union, vast Stalinist bureaucracies had smothered economic growth, with officials who wielded unchecked power resisting change that threatened their privileges.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, tried to break the hold of these bureaucrats on the economy by opening up the political system. Decades later, Chinese officials still take classes on why that was a mistake. The party even produced a documentary series on the subject in 2006, distributing it on classified DVDs for officials at all levels to watch.

Afraid to open up politically but unwilling to stand still, the party found another way. It moved gradually and followed the pattern of the compromise at Moganshan, which left the planned economy intact while allowing a market economy to flourish and outgrow it.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chinese Economics Thread

- Thread starter Norfolk

- Start date

Continued...

Party leaders called this go-slow, experimental approach “crossing the river by feeling the stones” — allowing farmers to grow and sell their own crops, for example, while retaining state ownership of the land; lifting investment restrictions in “special economic zones,” while leaving them in place in the rest of the country; or introducing privatization by selling only minority stakes in state firms at first.

“There was resistance,” Mr. Xu said. “Satisfying the reformers and the opposition was an art.”

American economists were skeptical. Market forces needed to be introduced quickly, they argued; otherwise, the bureaucracy would mobilize to block necessary changes. After a visit to China in 1988, the Nobel laureate Milton Friedman called the party’s strategy “an open invitation to corruption and inefficiency.”

But China had a strange advantage in battling bureaucratic resistance. The nation’s long economic boom followed one of the darkest chapters of its history, the Cultural Revolution, which decimated the party apparatus and left it in shambles. In effect, autocratic excess set the stage for Mao’s eventual successor, Deng Xiaoping, to lead the party in a radically more open direction.

That included sending generations of young party officials to the United States and elsewhere to study how modern economies worked. Sometimes they enrolled in universities, sometimes they found jobs, and sometimes they went on brief “study tours.” When they returned, the party promoted their careers and arranged for others to learn from them.

At the same time, the party invested in education, expanding access to schools and universities, and all but eliminating illiteracy. Many critics focus on the weaknesses of the Chinese system — the emphasis on tests and memorization, the political constraints, the discrimination against rural students. But mainland China now produces more graduates in science and engineering every year than the United States, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan combined.

In cities like Shanghai, Chinese schoolchildren outperform peers around the world. For many parents, though, even that is not enough. Because of new wealth, a traditional emphasis on education as a path to social mobility and the state’s hypercompetitive college entrance exam, most students also enroll in after-school tutoring programs — a market worth $125 billion, according to , or as much as half the government’s .

Another explanation for the party’s transformation lies in bureaucratic mechanics. Analysts sometimes say that China embraced economic reform while resisting political reform. But in reality, the party made changes after Mao’s death that fell short of free elections or independent courts yet were nevertheless significant.

The party introduced term limits and mandatory retirement ages, for example, making it easier to flush out incompetent officials. And it revamped the internal report cards it used to evaluate local leaders for promotions and bonuses, focusing them almost exclusively on concrete economic targets.

These seemingly minor adjustments had an outsize impact, injecting a dose of accountability — and competition — into the political system, said Yuen Yuen Ang, a political scientist at the University of Michigan. “China created a unique hybrid,” she said, “an .”

As the economy flourished, officials with a single-minded focus on growth often ignored widespread pollution, violations of labor standards, and tainted food and medical supplies. They were rewarded with soaring tax revenues and opportunities to enrich their friends, their relatives and themselves. A wave of officials abandoned the state and went into business. Over time, the party elite amassed great wealth, which cemented its support for the privatization of much of the economy it once controlled.

The private sector now produces more than 60 percent of the nation’s economic output, employs over 80 percent of workers in cities and towns, and generates 90 percent of new jobs, a senior official said . As often as not, the bureaucrats stay out of the way.

“I basically don’t see them even once a year,” said James Ni, chairman and founder of Mlily, a mattress manufacturer in eastern China. “I’m creating jobs, generating tax revenue. Why should they bother me?”

In recent years, President Xi has sought to assert the party’s authority inside private firms. He has also bolstered state-owned enterprises with subsidies while preserving barriers to foreign competition. And he has endorsed demands that American companies surrender technology in exchange for market access.

In doing so, he is betting that the Chinese state has changed so much that it should play a leading role in the economy — that it can build and run “national champions” capable of outcompeting the United States for control of the high-tech industries of the future. But he has also provoked a backlash in Washington.

In December, the Communist Party will celebrate the 40th anniversary of the “reform and opening up” policies that transformed China. The triumphant propaganda has already begun, with Mr. Xi , as if taking a victory lap for the nation.

He is the party’s most powerful leader since Deng and the son of a senior official who served Deng, but even as he wraps himself in Deng’s legacy, Mr. Xi has set himself apart in an important way: Deng encouraged the party to seek help and expertise overseas, but Mr. Xi preaches self-reliance and warns of the threats posed by “hostile foreign forces.”

In other words, he appears to have less use for the “opening up” part of Deng’s slogan.

Of the many risks that the party took in its pursuit of growth, perhaps the biggest was letting in foreign investment, trade and ideas. It was an exceptional gamble by a country once as isolated as North Korea is today, and it paid off in an exceptional way: China tapped into a wave of globalization sweeping the world and emerged as the world’s factory. China’s embrace of the internet, within limits, helped make it a leader in technology. And foreign advice helped China reshape its banks, build a legal system and create modern corporations.

The party prefers a different narrative these days, presenting the economic boom as “grown out of the soil of China” and primarily the result of its leadership. But this obscures one of the great ironies of China’s rise — that Beijing’s former enemies helped make it possible.

Continued ...

The United States and Japan, both routinely vilified by party propagandists, became major trading partners and were important sources of aid, investment and expertise. The real game changers, though, were people like Tony Lin, a factory manager who made his first trip to the mainland in 1988.

Mr. Lin was born and raised in Taiwan, the self-governing island where those who lost the Chinese civil war fled after the Communist Revolution. As a schoolboy, he was taught that mainland China was the enemy.

But in the late 1980s, the sneaker factory he managed in central Taiwan was having trouble finding workers, and its biggest customer, Nike, suggested moving some production to China. Mr. Lin set aside his fears and made the trip. What he found surprised him: a large and willing work force, and officials so eager for capital and know-how that they offered the use of a state factory free and a five-year break on taxes.

Mr. Lin spent the next decade shuttling to and from southern China, spending months at a time there and returning home only for short breaks to see his wife and children. He built and ran five sneaker factories, including Nike’s largest Chinese supplier.

“China’s policies were tremendous,” he recalled. “They were like a sponge absorbing water, money, technology, everything.”

Mr. Lin was part of a torrent of investment from ethnic Chinese enclaves in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and beyond that washed over China — and gave it a leg up on other developing countries. Without this diaspora, some economists argue, the mainland’s transformation might have stalled at the level of a country like Indonesia or Mexico.

The timing worked out for China, which opened up just as Taiwan was outgrowing its place in the global manufacturing chain. China benefited from Taiwan’s money, but also its managerial experience, technology and relationships with customers around the world. In effect, Taiwan jump-started capitalism in China and plugged it into the global economy.

Before long, the government in Taiwan began to worry about relying so much on its onetime enemy and tried to shift investment elsewhere. But the mainland was too cheap, too close and, with a common language and heritage, too familiar. Mr. Lin tried opening factories in Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia but always came back to China.

Now Taiwan finds itself increasingly dependent on a much more powerful China, which is pushing ever harder for unification, and the island’s future is uncertain.

There are echoes of Taiwan’s predicament around the world, where many are having second thoughts about how they rushed to embrace Beijing with trade and investment.

The remorse may be strongest in the United States, which brought China into the World Trade Organization, became China’s largest customer and now accuses it of large-scale theft of technology — what one official called “.”

Many in Washington predicted that trade would bring political change. It did, but not in China. “Opening up” ended up strengthening the party’s hold on power rather than weakening it. The , however, was felt in factory towns around the world.

In the United States, economists say as a result, many in districts that ended up .

Selective Repression

Over lunch at a luxurious private club on the 50th floor of an apartment tower in central Beijing, one of China’s most successful real estate tycoons explained why he had left his job at a government research center after the crackdown on the student-led democracy movement in Tiananmen Square.

“It was very easy,” said Feng Lun, the chairman of Vantone Holdings, which manages a multibillion-dollar portfolio of properties around the world. “One day, I woke up and everyone had run away. So I ran, too.”

Until the soldiers opened fire, he said, he had planned to spend his entire career in the civil service. Instead, as the party was pushing out those who had sympathized with the students, he joined the exodus of officials who started over as entrepreneurs in the 1990s.

“At the time, if you held a meeting and told us to go into business, we wouldn’t have gone,” he recalled. “So this incident, it unintentionally planted seeds in the market economy.”

Such has been the seesaw pattern of the party’s success.

The pro-democracy movement in 1989 was the closest the party ever came to political liberalization after Mao’s death, and the crackdown that followed was the furthest it went in the other direction, toward repression and control. After the massacre, the economy stalled and retrenchment seemed certain. Yet three years later, Deng used a tour of southern China to wrestle the party back to “reform and opening up” once more.

Many who had left the government, like Mr. Feng, suddenly found themselves leading the nation’s transformation from the outside, as its first generation of private entrepreneurs.

Now Mr. Xi is steering the party toward repression again, tightening its grip on society, concentrating power in his own hands and setting himself up to rule for life by abolishing the presidential term limit. Will the party loosen up again, as it did a few years after Tiananmen, or is this a more permanent shift? If it is, what will it mean for the Chinese economic miracle?

The fear is that Mr. Xi is attempting to rewrite the recipe behind China’s rise, replacing selective repression with something more severe.

The party has always been vigilant about crushing potential threats — a fledgling , a popular , even a . But with some big exceptions, it has also generally retreated from people’s personal lives and given them enough freedom to keep the economy growing.

The internet is an example of how it has benefited by striking a balance. The party let the nation go online with barely an inkling of what that might mean, then reaped the economic benefits while controlling the spread of information that could hurt it.

In 2011, it confronted a crisis. After a in eastern China, more than 30 million messages criticizing the party’s handling of the fatal accident flooded social media — faster than censors could screen them.

Panicked officials considered shutting down the most popular service, Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, but the authorities were afraid of how the public would respond. In the end, they let Weibo stay open but invested much more in tightening controls and ordered companies to do the same.

The compromise worked. Now, many companies assign hundreds of employees to censorship duties — and China has become a giant on the global internet landscape.

“The cost of censorship is quite limited compared to the great value created by the internet,” said Chen Tong, an industry pioneer. “We still get the information we need for economic progress.”

Last paragraphs

A ‘New Era’

China is not the only country that has squared the demands of authoritarian rule with the needs of free markets. But it has done so for longer, at greater scale and with more convincing results than any other.

The question now is whether it can sustain this model with the United States as an adversary rather than a partner.

The trade war has only just begun. And it is not just a trade war. American warships and planes are challenging Chinese claims to disputed waters with increasing frequency even as China keeps ratcheting up military spending. And Washington is maneuvering to counter Beijing’s growing influence around the world, warning that a Chinese spending spree on global infrastructure comes with strings attached.

The two nations may yet reach some accommodation. But both left and right in America have portrayed China as the champion of an alternative global order, one that embraces autocratic values and undermines fair competition. It is a rare consensus for the United States, which is deeply divided about so much else, including how it has wielded power abroad in recent decades — and how it should do so now.

Mr. Xi, on the other hand, has shown no sign of abandoning what he calls “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Some in his corner have been itching to take on the United States since the 2008 financial crisis and see the Trump administration’s policies as proof of what they have always suspected — that America is determined to keep China down.

At the same time, there is also widespread anxiety over the new acrimony, because the United States has long inspired admiration and envy in China, and because of a gnawing sense that the party’s formula for success may be faltering.

Prosperity has brought rising expectations in China; the public wants more than just economic growth. It wants cleaner air, safer food and medicine, better health care and schools, less corruption and greater equality. The party is struggling to deliver, and tweaks to the report cards it uses to measure the performance of officials hardly seem enough.

“The basic problem is, who is growth for?” said Mr. Xu, the retired official who wrote the Moganshan report. “We haven’t solved this problem.”

Growth has begun to slow, which may be better for the economy in the long term but could shake public confidence. The party is investing ever more in censorship to control discussion of the challenges the nation faces: widening inequality, dangerous debt levels, an aging population.

Mr. Xi himself has acknowledged that the party must adapt, declaring that the nation is entering a “new era” requiring new methods. But his prescription has largely been a throwback to repression, including targeting Muslim ethnic minorities. “Opening up” has been replaced by an outward push, with huge loans that critics describe as predatory and other efforts to gain influence — or interfere — in the politics of other countries. At home, experimentation is out while political orthodoxy and discipline are in.

In effect, Mr. Xi seems to believe that China has been so successful that the party can return to a more conventional authoritarian posture — and that to survive and surpass the United States it must.

Certainly, the momentum is still with the party. Over the past four decades, economic growth in China has been 10 times faster than in the United States, and it is still more than twice as fast. The party appears to enjoy broad public support, and many around the world are convinced that Mr. Trump’s America is in retreat while China’s moment is just beginning.

Then again, China has a way of defying expectations.

China power generation up 7.2% from Jan-Oct YoY. In Oct hydro up 6.2%, solar up 18.8%, nuclear 25.1%, thermal 3% and wind 4.2% YoY respectively.

China commences construction of longest 2 deck suspension bridge of 1700m span with six lanes on each deck to be completed by next Oct:

China commences construction of longest 2 deck suspension bridge of 1700m span with six lanes on each deck to be completed by next Oct:

Last edited:

China reducing desertified land by 1900km^2 per year versus a loss of 3600km^2 per year:

China reduced rural left behind children by 22.7% from 2016 to roughly 6.97 million:

Chinese box office to 7.62 billion USD up 9.75% YoY from Jan with 70% of sales from domestic films

China reduced rural left behind children by 22.7% from 2016 to roughly 6.97 million:

Chinese box office to 7.62 billion USD up 9.75% YoY from Jan with 70% of sales from domestic films

OK, just to be clear, the housing discussion is over. I have fully laid out how China will continue to grow its middle class and this is to the concurrence of the fact that every year, more and more Chinese people are able to afford the housing, despite its expense.

Now I will continue to educate you on the new topic you started: transition of power from the few elite to the many common people.

Just to make clear: the expensive housing is a way to keep the elite in power even with increasing wage pool.

And the growing of middle class is nothing else but the transfer of the most important power - the economical from the elite to the population.

And the elite has less wealth compared to the masses, compared to China. Simple, isn't it?That said, the USA/Europe are wealthier than China on a per capita measure simply because its citizens have more stuff/money.

And that's not to mention that your entire claim that there is more power to the masses in the US than in China (without regard to voting rights) is incorrect and unsubstantiated. I have lived in both countries and I don't feel any different in terms of power or significance in either. The biggest difference is that in the US, I know that the police kill people for no reason so I'm much more relaxed when the police are involved in a situation in China than in the USA. If anything, it makes me feel more vulnerable and less empowered as a citizen in the US than in China.

The average USA citizen command (or used to command) more resources from the economy than the average Chinese. I don't talk about money, but the % of GDP that is in the hand of the average Chinese vs average USA citizen.

That is mathematically impossible for the masses to be wiser than the few; that is like saying that the average value of 1 million numbers is larger than the 5 highest outliers.

IT is exactly the opposite.

100 person can collect better information and can make better decision than one, regardless of intelligence.

Even the brightest is incapable to command a 1000 person business with understanding of the main aspects of it.

Rule by the masses

1. has no coordination. Without hierarchy, no one can determine the outcome; it will be perpetual argument.

2. means that the stupid will always outnumber the smart by a vast margin and drown out the voices of those who have better ideas than the simple/obvious ones.

3. has no ability to keep plans in secret. Opposing (foreign) forces will have luxurious lead time to counter.

4. is short-sighted and skewed for immediate gratitude rather than long-term solution. It takes calm and patience to develop the latter; mobs don't have it.

5. Is not a form of government used anywhere in the civilized world. Voting is the closest to mass rule as it gets in any functioning country.

Rule by the elite

1. can select extremely talented individuals to take command with solutions so ingenious that average people don't even comprehend them.

2. can deploy those plans efficiently; a council can move much faster than a national vote/mob fight.

3. can deploy those plans in secrecy, leaving antagonists with little to no reaction time.

4. Is susceptible to corruption, but the risk can be mitigated by structure and the nationalism.

5. Is employed in every civilized government in the world as the only way to organize a country.

This applies to Switzerland, not China. Switzerland is small, inconsequential, and poses no threat to anyone. It is a fly living its life with no disturbance and no significance; it's a very enjoyable way of living. China is a tiger; tigers are challenged by other large territorial beasts on a daily basis. Bears, lions, panthers etc... all wait to see weakness in the tiger to snatch his territory and deal him injury. To the tiger, the only way to live well is to be disciplined and to build elite power.

The only way the Chinese can live well is to operate as much like a military unit as a vast country of civilians can; if it is disorganized, if it is not ready, then India, Japan, USA will all jump at the oppertunity to humiliate and rob it.

You have no choice but to trust these politicians because there is no such thing as rule by the masses. Rule by the masses is what happens in the last few weeks before a country collapses. As a matter of fact, your entire vision of transfer of power from the few to the many is completely unclear. Most people would assume that meant democratic voting rights. What exactly the hell do you think that means? Describe a model and keep in mind, it needs to be suitable for China, not Switzerland.

For the economy / average person the most important is the low entropy in regards of economical stability. Everything is secondary.

And it is easy to prove the best economical system is the one that fine grained, and capable to use the available resources with the highest efficiency.

But it means that the best system is the one that can manage the requirements on micro level, delegating the decision making capability and resources to that level, and at the same time for the macro decisions can collect and analyse all relevant information from the micro level.

This is next to impossible for a central government, regardless of the type that it has .

Best is if the low level decision makers settle the macro level design between each other.

Now we have the required infrastructure for it, it is only a matter of learning/debugging to make it work .

The reason why the West is wealthier than China and India is because the West has industrialized a hundred years earlier than the rest of the world. Not because of democracy. There is now a growing dissatisfaction in the West as well because of the systems inability to solve the pressing problems of the day. In a system where everyone just can say anything creates a situation where there are a lot of opinions but no solutions. Because of the lack of consensus. In a system where every little detail is being discussed a hundred times over creates a situation where people can't see the forrest through the trees. Which also helps to leave the bigger problems unadressed. In a system where people are looking at elections every 4 or 5 years means long term planning is extremely difficult. In a system where different ideas have to compete means people are more driven by their ideology rather than pragmatism.You don't capture the magnitude / complexity of issue, and the motivation of the affected parties.

USA / Europe wealthy not because they have a lot of paper/ electronics currency, but because the citizens of those countries has bigger say about the events than say in India or China.

And this is not simply about "elections" ,that is small part of the story , it is about legal system, applicability of law onto everyone, freedom of business and independent juridical system.

Think about the ratio between the salaries and business profit on a full economy level like recognise who hold the real power in the economy.

If the business makes less ( more less) profit than the wage pool of workers then the workers has the power. And will end in a massive collapse.

The increase of wages doesn't simply a numerical value for factory owners , but means money can not buy any more profit opportunity , only knowledge and capability.

Electoral power and so on came from this, and can be built onto this, not the opposite way around.

So saying that "it is just simply faster increase of wages than the GDP growth" is like calling the ice age as a "a bit cold weather".

The elections only an insignificant part of the story.

And generally, the masses are more wise than the few, the best become idiot when infected by the corruption of power. China is not exception, only the fast rise from extreme deep poverty masked it for few decade.

See Switzerland. Compare its story with China in the past 150 years since the tenure of Cixi.

The country is not a military unit, that has to execute a command precisely .

The country is a group of people, who want to live undisturbed and well. The politicians wants to push they own cart, not the chasing the interest of the country.

There was few politicians in the history who valued his standing and power less than the interest of the people . And even the best start to spend best part of his time to keep on power when realise the successors are more ruthless and self centred than them.

Democracy has a lot of advantages but its by no means perfect and not recognising that will be its undoing.

Increases in wages and living standards comes from higher productivity and efficiency. Higher productivity comes from investments in people and capital goods. This is the way that both the owners and the workers can benefit. The problem in the West today is the lack of capital investment into the REAL economy. Rather money has gone into speculation like bonds, real estate, stocks and securities. Its also the effect of the lack of savings. The debt pile up in the West has helped to create asset bubbles rather than increase production. Which in turn helps to create the growing gap between rich and poor. And will end in a massive collapse

Last edited:

manqiangrexue

Brigadier

Just to be clear, that is completely your unsupported theory that the Chinese government purposefully and artificially keeps housing prices high so that poor people remain poor. This is found nowhere except in your imagination. This is actually conspiracy territory. But also, it still doesn't change the bottom line, that every year, more and more Chinese people can afford urban housing.Just to make clear: the expensive housing is a way to keep the elite in power even with increasing wage pool.

I can't explain the same things over and over. There is no transfer in China; there is growth. Europe can do the transfer all night and all day. China just grows so both the rich and poor get richer.And the growing of middle class is nothing else but the transfer of the most important power - the economical from the elite to the population.

It's awesome when you call something "simple" because it makes it that much funnier when you make a fool out of yourself LOL. You're confusing correlation with causation. Just saying that 2 things happen together doesn't mean that one causes the other. And also, you didn't show that in the west (or the US), citizens have more power than in China (especially after you rejected voting rights as a factor).And the elite has less wealth compared to the masses, compared to China. Simple, isn't it?

That is an observation connected with nothing else.The average USA citizen command (or used to command) more resources from the economy than the average Chinese. I don't talk about money, but the % of GDP that is in the hand of the average Chinese vs average USA citizen.

You have clearly never worked in a team before. This is so basic, it's insane that I have to explain this to an adult, if you are one. Teams must have leaders, sometimes several layers of leaders analogous to a hierarchy of the ruling elite. I have never seen a team without leadership featuring just 100 people with different opinions arguing with each other and doing their thing before. They will never coordinate themselves to achieve anything.IT is exactly the opposite.

100 person can collect better information and can make better decision than one, regardless of intelligence.

The brightest of these is called the CEO and he can have 100 or 1000 or 10,000 people working for him. This is how all companies work. And obviously, he needs to understand the main aspects. They do in real life. I never said use someone who doesn't understand the business to be the leader. This concept is so basic that having to explain it is like talking to a child with no experience in the world...Even the brightest is incapable to command a 1000 person business with understanding of the main aspects of it.

If it's next to impossible for a central government, then it's actually impossible for a mob to achieve this. You have a group of 1,000 opinionated people confused with 1,000 ants. People don't work like that.For the economy / average person the most important is the low entropy in regards of economical stability. Everything is secondary.

And it is easy to prove the best economical system is the one that fine grained, and capable to use the available resources with the highest efficiency.

But it means that the best system is the one that can manage the requirements on micro level, delegating the decision making capability and resources to that level, and at the same time for the macro decisions can collect and analyse all relevant information from the micro level.

This is next to impossible for a central government, regardless of the type that it has .

Best is if the low level decision makers settle the macro level design between each other.

Who's we? Most importantly, I have previously laid out that every government in the world uses the ruling elite to command the masses. What is an example of your ideal model? Right now, it looks like you want a country with no leaders and everyone doing their own thing. In your imagination, they will work like ants and achieve a new level of efficiency. If this is what you mean, this is total fantasy land and I'm clearly wasting my time talking to a crazy person.Now we have the required infrastructure for it, it is only a matter of learning/debugging to make it work .

Last edited:

Hendrik_2000

Lieutenant General

Mangiang is right the trick is enlarge the economy and not to transfer the wealth. Just like eating pie what would you rather have a smaller pie that is divided equally or Wait for much larger pie so that each can have larger share of the pie?. And empower people to help themselves instead of handing out welfare check or government largess. Education should be free and cutting red tape, foster private company, good infrastructure.efficient government And stop being dogmatic use pragmatic-ism

A timely article from NYT. I applauded NYT effort to tell the truth instead of myth and prejudice. I guess it slowly dawn on this people that China miracle is mainly due to their own hardwork and good choice of policy. And not due to assistance So China is right when she said China does not owe to anybody or scare of intimidation

Xu Liya, 49, once tilled wheat fields in Zhejiang, a rural province along China’s east coast. Her family ate meat only once a week, and each night she crammed into a bedroom with seven relatives.

Then she attended university on a scholarship and started a clothing store. Now she owns two cars and an apartment valued at more than $300,000. Her daughter attends college in Beijing.

“Poverty and corruption have hurt average people in China for too long,” she said. “While today’s society isn’t perfect, poor people have the resources to compete with rich people, too.”

The American Dream Is Alive. In China.

By JAVIER C. HERNÁNDEZ and QUOCTRUNG BUI NOV. 18, 2018

China is still much poorer over all than the United States. But the Chinese have taken a commanding lead in that most intangible but valuable of economic indicators: optimism.

In a country still haunted by the Cultural Revolution, where politics are tightly circumscribed by an authoritarian state, the Chinese are now among the most optimistic people in the world — much more so than Americans and Europeans, according to public opinion surveys.

What has changed?

Most of all, an economic expansion without precedent in modern history.

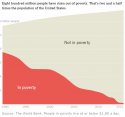

Eight hundred million people have risen out of poverty. That’s two and a half times the population of the United States.

Source: The World Bank. People in poverty live at or below $1.90 a day.

Not only are incomes drastically rising within families, but sons are outearning their fathers. That means expectations are rising, too, especially among China’s growing middle class.

Life expectancy has also soared. Chinese men born in 2013 are expected to live more than seven years longer than those born in 1990; women are expected to live nearly 10 years longer.

“It feels like there are no limits to how far you can go,” said Wu Haifeng, 37, a financial analyst who was born to a family of corn farmers in northern China and now earns more than $78,000 a year. “It feels like China will always be strong.”

China used to make up much of the world’s poor. Now it makes up much of the world’s middle class.

2016

China

010th20th30th40th50th60th70th80th90th100thWorld's Richest →← World's PoorestINCOME PERCENTILE

Source: World Inequality Database

There are risks, of course, and no guarantees that China’s rise will continue indefinitely.

A prolonged economic slump could inflict major damage. And experts warn that China could fall into the middle-income trap — in which growth and earnings plateau — if it fails to address high corporate debt levels or doesn’t do more to encourage innovation. Demography is also a ticking bomb: China is racing to get rich before it gets old.

Yet for now, the economic arc seems ever upward.

Like the United States, China still has a yawning gap between the rich and the poor — and the poorest Chinese are far poorer, with nearly 500 million people, or about 40 percent of the population, living on less than $5.50 a day, according to the World Bank.

But by some measures Chinese society has about the same level of inequality as the United States. Here are the world’s major countries ordered by inequality and income mobility. (A previous version of this chart has been corrected.)

Source: The World Bank,

Today, the economic output per capita in China is $12,000, compared with $3,500 a decade ago. The number is far higher in the United States, $53,000.

Yet few analysts doubt where the bigger increases will come. Here’s how modern China’s per-capita G.D.P. growth compares so far:

Number of years since each country reached China’s per-capita G.D.P. in 1993

In 2011 U.S. dollars. |Source: Maddison Project.

China’s progress is especially remarkable given how the government has used social engineering to restrict where people live and how many children they have. Loosening those constraints could accelerate income growth.

This is why many people now talk about “the Chinese Dream.”

Xu Liya, 49, once tilled wheat fields in Zhejiang, a rural province along China’s east coast. Her family ate meat only once a week, and each night she crammed into a bedroom with seven relatives.

Then she attended university on a scholarship and started a clothing store. Now she owns two cars and an apartment valued at more than $300,000. Her daughter attends college in Beijing.

“Poverty and corruption have hurt average people in China for too long,” she said. “While today’s society isn’t perfect, poor people have the resources to compete with rich people, too.”

A timely article from NYT. I applauded NYT effort to tell the truth instead of myth and prejudice. I guess it slowly dawn on this people that China miracle is mainly due to their own hardwork and good choice of policy. And not due to assistance So China is right when she said China does not owe to anybody or scare of intimidation

Xu Liya, 49, once tilled wheat fields in Zhejiang, a rural province along China’s east coast. Her family ate meat only once a week, and each night she crammed into a bedroom with seven relatives.

Then she attended university on a scholarship and started a clothing store. Now she owns two cars and an apartment valued at more than $300,000. Her daughter attends college in Beijing.

“Poverty and corruption have hurt average people in China for too long,” she said. “While today’s society isn’t perfect, poor people have the resources to compete with rich people, too.”

The American Dream Is Alive. In China.

By JAVIER C. HERNÁNDEZ and QUOCTRUNG BUI NOV. 18, 2018

China is still much poorer over all than the United States. But the Chinese have taken a commanding lead in that most intangible but valuable of economic indicators: optimism.

In a country still haunted by the Cultural Revolution, where politics are tightly circumscribed by an authoritarian state, the Chinese are now among the most optimistic people in the world — much more so than Americans and Europeans, according to public opinion surveys.

What has changed?

Most of all, an economic expansion without precedent in modern history.

Eight hundred million people have risen out of poverty. That’s two and a half times the population of the United States.

Source: The World Bank. People in poverty live at or below $1.90 a day.

Not only are incomes drastically rising within families, but sons are outearning their fathers. That means expectations are rising, too, especially among China’s growing middle class.

Life expectancy has also soared. Chinese men born in 2013 are expected to live more than seven years longer than those born in 1990; women are expected to live nearly 10 years longer.

“It feels like there are no limits to how far you can go,” said Wu Haifeng, 37, a financial analyst who was born to a family of corn farmers in northern China and now earns more than $78,000 a year. “It feels like China will always be strong.”

China used to make up much of the world’s poor. Now it makes up much of the world’s middle class.

2016

China

010th20th30th40th50th60th70th80th90th100thWorld's Richest →← World's PoorestINCOME PERCENTILE

Source: World Inequality Database

There are risks, of course, and no guarantees that China’s rise will continue indefinitely.

A prolonged economic slump could inflict major damage. And experts warn that China could fall into the middle-income trap — in which growth and earnings plateau — if it fails to address high corporate debt levels or doesn’t do more to encourage innovation. Demography is also a ticking bomb: China is racing to get rich before it gets old.

Yet for now, the economic arc seems ever upward.

Like the United States, China still has a yawning gap between the rich and the poor — and the poorest Chinese are far poorer, with nearly 500 million people, or about 40 percent of the population, living on less than $5.50 a day, according to the World Bank.

But by some measures Chinese society has about the same level of inequality as the United States. Here are the world’s major countries ordered by inequality and income mobility. (A previous version of this chart has been corrected.)

Source: The World Bank,

Today, the economic output per capita in China is $12,000, compared with $3,500 a decade ago. The number is far higher in the United States, $53,000.

Yet few analysts doubt where the bigger increases will come. Here’s how modern China’s per-capita G.D.P. growth compares so far:

Number of years since each country reached China’s per-capita G.D.P. in 1993

In 2011 U.S. dollars. |Source: Maddison Project.

China’s progress is especially remarkable given how the government has used social engineering to restrict where people live and how many children they have. Loosening those constraints could accelerate income growth.

This is why many people now talk about “the Chinese Dream.”

Xu Liya, 49, once tilled wheat fields in Zhejiang, a rural province along China’s east coast. Her family ate meat only once a week, and each night she crammed into a bedroom with seven relatives.

Then she attended university on a scholarship and started a clothing store. Now she owns two cars and an apartment valued at more than $300,000. Her daughter attends college in Beijing.

“Poverty and corruption have hurt average people in China for too long,” she said. “While today’s society isn’t perfect, poor people have the resources to compete with rich people, too.”

Last edited: