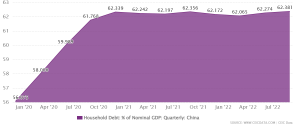

There are some 600 projects in China that had consumers stop paying mortgages in July - most pronounced in Zhengzhou - I actually spoke to someone as a part of the team in charge of fixing the problem there and lets just say this will take time to flow through.

Yes. But look at the fundamentals of Zhengzhou. It is the capital of Henan Province with some 100 Mn people with only a 56% urbanisation rate.

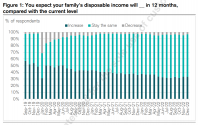

I think you're conflating what will happen *IF* consumer confidence comes back overnight with what *is likely* to happen. Mathematically what you are getting is possible but that isn't a base case scenario. The alternative data I track on restaurants and mobility would suggest a strong recovery but not nearly back to 2019 levels. The "Stuff to Service" shift is happening here as well.

Whilst urban areas are effectively at herd immunity, that is not true of rural areas. So there's a smaller 2nd wave still to occur when people go back to their family homes next week for Chinese New Year.

Then there will be another even smaller wave when they return to work in the cities, but I expect this to be very limited.

So I wouldn't expect restaurant or mobility data to be back to 2019 yet. Hence my comment that we'll see large effects after Chinese New Year. Remember that much of consumer sentiment is simply the herd effect, and the herd is moving.

The recovery is not going to be nearly as explosive as we saw in the DM because all the subsidies in China were given to the 'supply side' and virtually none given to the 'demand side'. The rich people aren't impacted, but keep in mind MPC is much lower for rich people than it is for poor people.

Also keep in mind, if your argument is that retail sales will be stronger, then net exports in 2023 will mathematically be weaker. You can't have it both ways here. Additionally, outbound travel will further erode net-exports - as the Top 10% of people in China with passports go to HK/Macao/Japan/Korea/Thailand.

China already has way enough foreign currency reserves,

Net exports are also at record levels.

So China doesn't need or want excessive amounts of foreign currency that it can't spend, and which is liable to confiscation by the US. That is one of the lessons of Russia.

So a reduction in net exports is perfectly acceptable to China.

An increase in imports is also desirable from the Chinese perspective, as it will soothe concerns of trading partners.

Can you break down the composition of solar investment? Not all of it will be counted as GDP (importing energy to make silicon ingots isn't all added to Chinese GDP - what is the *value added* portion of that investment?) - quoting a number like that without decomposing that is really not persuasive.

If solar panels are installed in China, I expect 95%+ of the project value to be Chinese-value add.

The import component is basically sand and maybe a few specialty bits. Everything else (which includes the electricity) is generated or made from domestic sources (coal, solar, wind, nuclear, hydro in China).

At this point, China already has 80% of the global entire solar industry and an even higher percentage of the underlying supply chain from start to finish.

For overseas solar projects, I expect most (but not all) of the project value will be Chinese value-add. My gut says 70% maximum.

In 2022 China added 120GW of Wind + Solar. The target set by the National Energy Administration literally 2 weeks ago between wind and solar in China is 160 GW for 2023.

Globally, BNEF expects 2023 to be 315 GW of solar addition (vs. 268 GW in 2022) - if you are saying all of that 350 GW of capacity coming online in 2023 - wafer prices will compress some much that part of supply chain will go bankrupt.

What you are doing here is conflating supply addition with demand generation - just because China is building capacity doesn't mean people will use said capacity. And just because people use that capacity, doesn't mean that prices won't deflate as a result of significant oversupply.

We saw this movie in Aluminum and Steel, and we are watching this happen in real time with lithium battery capacity in 2023 - and we are about to see it happen with solar wafers.

I understand what you are saying.

But the big difference with Aluminium and Steel is that they reached the demand limit.

With solar and lithium, we're nowhere near the demand limit.

For example, the average electric vehicle has a higher upfront investment cost but significantly lower operating costs.

But say over a 10 year lifespan, the Total Cost of Ownership of a petrol car is 2x higher.

But once electric vehicles have a lower upfront cost (which is happening), you can see how they will completely displace combustion engine vehicles.

China is currently around 33% electric in terms of new sales. So EV sales (and therefore lithium demand) still has to triple before the Chinese market is saturated.

Once lithium prices come down from the current historic highs, the price of electric vehicles will further drop and stimulate extra demand to soak up that extra lithium capacity.

Consider how BYD currently produces affordable EVs and has a 5? month waiting list. BYD can produce these at a profit. So there is still much demand to fill in China. Then there is the global car market which still needs to go electric and also stationary grid storage in terms of lithium demand.

---

You have a similar story with solar panels which compete against coal in China for example.

Once solar electricity gets cheap enough, it will eat into coal power plant demand.

The interesting thing is the interplay between solar and electric vehicles, which is outlined in the Third Industrial Revolution. Tony Seba also goes into this.

In sunny Saudi for example, solar costs 2cents/KWh. In comparison, the cost of coal electricity would be 3x more expensive.

the problem is that you can't store this low-cost electricity, unless you have a battery.

Well, it just so happens that electric vehicles have a battery which can store this electricity for later use. The combination of solar panels being the lowest-cost form of electricity and cheap electric vehicle batteries results in a huge cost advantage over petrol cars.

Furthermore, the average EV car battery is sized for long road journeys, and is way more than what the average daily commuter uses. So this means the battery can also store all the electricity required to run a home for an entire day.

So again, you can see a virtuous relationship where [low-cost solar] + [low-cost EVs] displaces coal/gas electricity in the entire grid.

And the global opportunity is 30,000 TWh of electricity in say 3 years time. Say half of that can be covered by solar and you'll need roughly 15,000? GW of solar panels in total. Then you still have further increases in electricity demand.

So China being able to produce 3 million tonnes of polysilicon (1000GW of solar panels per year) is nowhere near meeting final demand for solar panels.

Remember that at the dawn of the automobile era, it only took 10 years for automobiles to completely replace horses in New York.