Continue due to size limits.

A photo shows Japanese settlers in northeast China practice fighting in preparation for battles. Photo taken at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021. Qi Jianqiang/CGTN

However, the Japanese government did not immediately notify the farmers. "They were afraid they would be a burden to post-war Japan, so they adopted a policy of 'abandoning emigrants'," explained Meng, who's studied the population of Japanese war orphans for years. "The low-level Japanese settlers were left to sink or swim."

After a few days of walking to rail stations or ports in the hope of returning to Japan, they were either exhausted or fell ill. Some mothers, hounded by hunger and disease, started to give up their children, starting with the youngest who couldn't walk. They either abandoned them in the hope that kindred locals would give them a chance to live or entrusted them to Chinese families. In the latter case, most mothers left a keepsake noting their name, birth, and home address in Japan, according to Meng.

There were also cases of military leaders ordering mothers to strangle their children for fear that their crying would reveal their whereabouts during the retreat. Tragedies abounded, in addition to hundreds of group suicides in the spirit of "Japanese militarism."

Incomplete statistics show more than 4,000 Japanese orphans under the age of 13 were left behind, 90 percent of them the offspring of emigrants.

In the overcast days after August 15, some 10,000 Japanese emigrants in Fangzheng tried to make their way to Harbin to catch a train back. "Cold, hungry, and trapped by Soviet soldiers, some 5,000 people died," Cao Songxian, director of Fangzheng's overseas Chinese federation, told us on the way to Xu's home. He pointed to the gun turrets and airports the Japanese built in the small county. "Babies were just crying along the dirt street, and local Chinese took them home."

Impoverished themselves, they managed to raise the children with all they could. "Everyone was living on very short commons in those tumultuous years but they'd starve themselves to feed the children," Meng said.

"My foster parents have five kids but I'm their favorite," said Sun, who has an elder sister and three younger cousins. "Every Spring Festival, I'm the only one in the family to wear new clothes while my sisters had to wear old coats and pants of mine." Moreover, she's also the only one among all the girls to have graduated from junior high, while all her sisters dropped out from elementary school. "Upon graduation, I became the first female tractor driver in Fangzheng," she exclaimed, wearing a proud look.

These Chinese parents also shielded the kids from any psychological trauma. Despite the myriad atrocities the Japanese imposed on him, Xu's foster father would take the issue up with the parents of the children who called her "little Jap." Once she got angry with her father for not allowing her to play with a kid in the neighborhood, only to learn later that he was protecting her. That was also something Liu Guizhi's foster parents would do every time she was bullied. Liu's story is more painful. She's orphaned twice – her stepfather gave her up and 13 years later her foster parents died of illness.

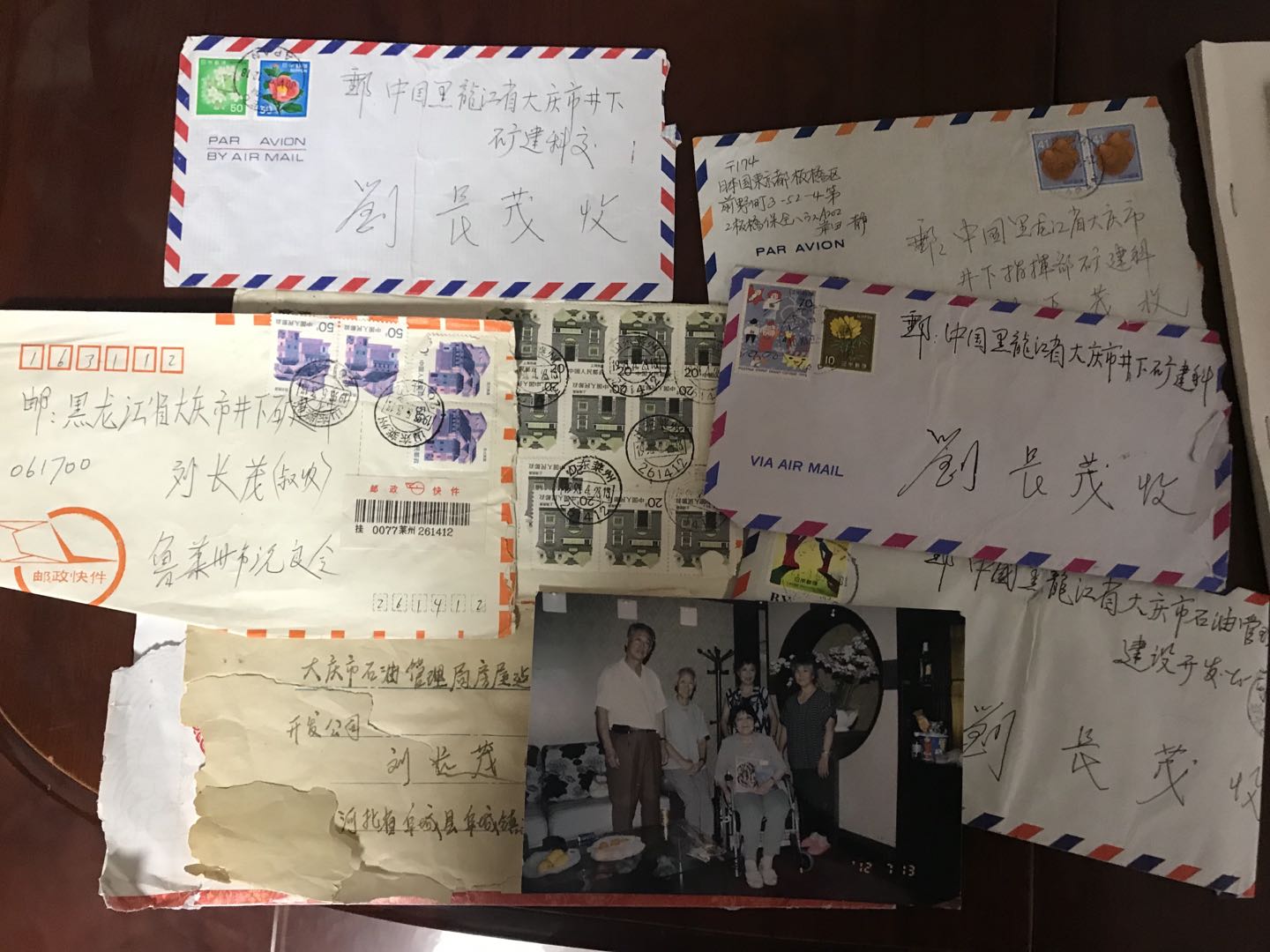

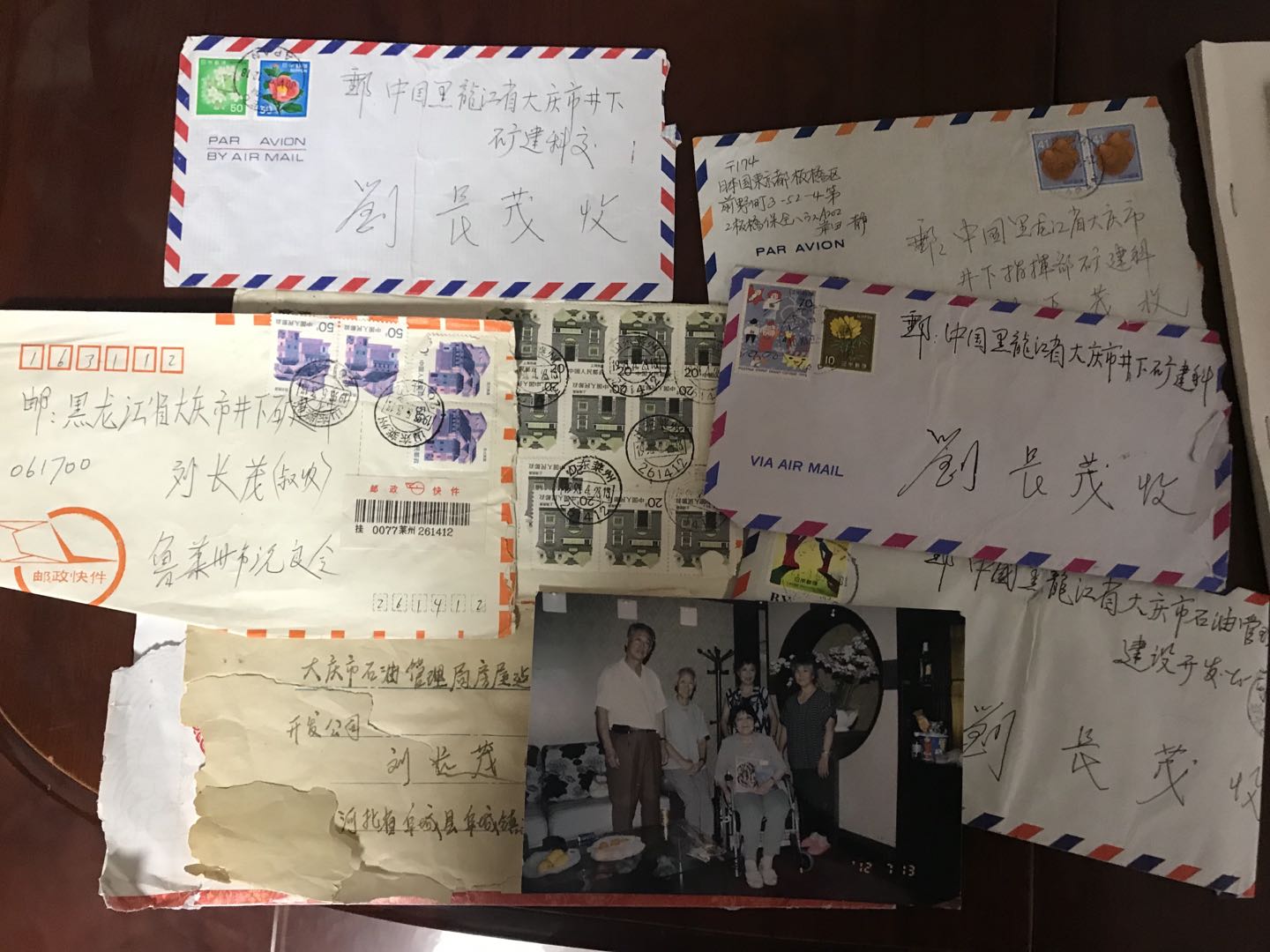

Letters between Liu Changmao and his Japanese sister Liu Guizhi, whose Japanese name is Keiko Matsuda. Photo taken in Liu Changmao's home in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, April 27, 2021. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

The three war orphans we reached out to have varied life trajectories, yet what ties them together is that they were all adopted and raised by Chinese families, married into Chinese families and don't speak good Japanese.

'China is my home, forever'

Not long after Liu was born in 1940, her father joined the Japanese emigrants to Harbin. Two years later, her biological mother eventually carried her on her back to look for her father. After a difficult journey, they were finally able to reach the settlement where her father was stationed, only to discover that he left to fight in the military. Penniless, they had to beg on the streets while they continued to look for him. One day news came that her father had died.

Her mother tied the knot again with a Japanese man who took Liu as a burden and gave her to a childless Chinese couple. "I was treated like a princess, even after my brother was born in 1947," she told us through the phone. She went back to Japan's Saitama Prefecture, her hometown, in 1990, under a repatriation program launched by both the Chinese and Japanese governments. The programs started in 1981, three years after the two countries established diplomatic ties. Liu was part of the second batch to return to Japan and took the name of Keiko Matsuda.

Japan has so far recognized 2,818 war orphans, among them 2,557 have gone back to Japan and 260 chose to stay. "Many chose to stay in China and there are also those who made it back to China after spending some time in Japan because of bias and discrimination, both conscious and unconscious," said Du Ying, director of the Institute of Japanese Studies at the Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences. "That part of history was basically in oblivion in the memories of many Japanese before the 1980s. So it's very difficult for the war orphans to live a decent life back in Japan."

Liu experienced a down period, taking as many part-time jobs as she could. But a tough woman, she managed to lead a happy life with her big family.

A monument dedicated to Chinese foster parents at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province. Over 1,000 Japanese war orphans donated money to build the monument in 1999. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Before our trip to Fangzheng, we arrived at Daqing, known as the oil city, to visit her Chinese brother Liu Changmao who's in his 70s now. They'd written to each other a few times every month before smartphones facilitated video communication.

"We are very close. My parents died when I was only six, my Japanese sister helped bring me up when we lived at our relatives' home in Shandong," Liu Changmao said. "Stay home. COVID-19 is rampant in Japan," he told his Japanese sister before hanging up.

In Japan, Liu Guizhi and other Japanese war orphans, have been helping to improve China-Japan ties – a relationship of entanglement imbued with love and hatred. In 2009, the elderly woman went to Beijing with a delegation of Japanese orphans and sang a song written by her Chinese husband to then Premier Wen Jiabao "China is my home forever."

In times of bilateral uncertainties, the orphans served as a bridge. In 1995, an orphan built a monument to Chinese foster parents in the China-Japan Friendship Garden – a cemetery then Premier Zhou Enlai ordered to construct in the 1960s in the memory of the over 5,000 Japanese who died in Fangzheng during their retreat. In 1999, over 1,000 orphans donated money to build another monument to Chinese foster parents inside the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang. There's also a China-Japan Amity House in Changchun, built exclusively to house elderly foster parents, which has remained empty since the last foster parent there died in late 2020.

"When the war orphans decided to go back to Japan, which recorded spectacular economic growth in the '80s and '90s, all their Chinese parents showed was encouragement no matter how reluctant they were," Meng said.

Du has been studying the population of Chinese parents who adopted Japanese orphans. According to her observation, these parents would always let the children choose their own path, even though some of them did not choose to have their own kids in order to create a better environment for the children of the enemy. "Children are innocent. They are also victims to the war."

For Liu Guizhi, Xu Shilan, Sun Yuqin, and others like them, the war is still very much part of their lives. Sometimes, Xu would stare at the smallpox vaccination scar on her left arm, which is different from the one for the Chinese, and the only mark her native country has left on her.

(Special thanks to the following people, in addition to the interviewees mentioned in the article, who helped tremendously with our reporting, offering their expertise and resources: Da Zhigang director and research fellow of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at the Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences, Lv Xiang, a retired professor of studies of Japan and Korea at the Liaoning Academy of Social Sciences, and Guo Xiangsheng, a folklore researcher in Fangzheng.)

Reporters: Wang Xiaonan, Bi Junxin

Writer: Wang Xiaonan

Video editor: Zhao Yue

Videographer: Qi Jianqiang

Yu Jing helped with video editing.

Cover image designer: Li Jingjie

A photo shows Japanese settlers in northeast China practice fighting in preparation for battles. Photo taken at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021. Qi Jianqiang/CGTN

However, the Japanese government did not immediately notify the farmers. "They were afraid they would be a burden to post-war Japan, so they adopted a policy of 'abandoning emigrants'," explained Meng, who's studied the population of Japanese war orphans for years. "The low-level Japanese settlers were left to sink or swim."

After a few days of walking to rail stations or ports in the hope of returning to Japan, they were either exhausted or fell ill. Some mothers, hounded by hunger and disease, started to give up their children, starting with the youngest who couldn't walk. They either abandoned them in the hope that kindred locals would give them a chance to live or entrusted them to Chinese families. In the latter case, most mothers left a keepsake noting their name, birth, and home address in Japan, according to Meng.

There were also cases of military leaders ordering mothers to strangle their children for fear that their crying would reveal their whereabouts during the retreat. Tragedies abounded, in addition to hundreds of group suicides in the spirit of "Japanese militarism."

Incomplete statistics show more than 4,000 Japanese orphans under the age of 13 were left behind, 90 percent of them the offspring of emigrants.

In the overcast days after August 15, some 10,000 Japanese emigrants in Fangzheng tried to make their way to Harbin to catch a train back. "Cold, hungry, and trapped by Soviet soldiers, some 5,000 people died," Cao Songxian, director of Fangzheng's overseas Chinese federation, told us on the way to Xu's home. He pointed to the gun turrets and airports the Japanese built in the small county. "Babies were just crying along the dirt street, and local Chinese took them home."

Impoverished themselves, they managed to raise the children with all they could. "Everyone was living on very short commons in those tumultuous years but they'd starve themselves to feed the children," Meng said.

"My foster parents have five kids but I'm their favorite," said Sun, who has an elder sister and three younger cousins. "Every Spring Festival, I'm the only one in the family to wear new clothes while my sisters had to wear old coats and pants of mine." Moreover, she's also the only one among all the girls to have graduated from junior high, while all her sisters dropped out from elementary school. "Upon graduation, I became the first female tractor driver in Fangzheng," she exclaimed, wearing a proud look.

These Chinese parents also shielded the kids from any psychological trauma. Despite the myriad atrocities the Japanese imposed on him, Xu's foster father would take the issue up with the parents of the children who called her "little Jap." Once she got angry with her father for not allowing her to play with a kid in the neighborhood, only to learn later that he was protecting her. That was also something Liu Guizhi's foster parents would do every time she was bullied. Liu's story is more painful. She's orphaned twice – her stepfather gave her up and 13 years later her foster parents died of illness.

Letters between Liu Changmao and his Japanese sister Liu Guizhi, whose Japanese name is Keiko Matsuda. Photo taken in Liu Changmao's home in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, April 27, 2021. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

The three war orphans we reached out to have varied life trajectories, yet what ties them together is that they were all adopted and raised by Chinese families, married into Chinese families and don't speak good Japanese.

'China is my home, forever'

Not long after Liu was born in 1940, her father joined the Japanese emigrants to Harbin. Two years later, her biological mother eventually carried her on her back to look for her father. After a difficult journey, they were finally able to reach the settlement where her father was stationed, only to discover that he left to fight in the military. Penniless, they had to beg on the streets while they continued to look for him. One day news came that her father had died.

Her mother tied the knot again with a Japanese man who took Liu as a burden and gave her to a childless Chinese couple. "I was treated like a princess, even after my brother was born in 1947," she told us through the phone. She went back to Japan's Saitama Prefecture, her hometown, in 1990, under a repatriation program launched by both the Chinese and Japanese governments. The programs started in 1981, three years after the two countries established diplomatic ties. Liu was part of the second batch to return to Japan and took the name of Keiko Matsuda.

Japan has so far recognized 2,818 war orphans, among them 2,557 have gone back to Japan and 260 chose to stay. "Many chose to stay in China and there are also those who made it back to China after spending some time in Japan because of bias and discrimination, both conscious and unconscious," said Du Ying, director of the Institute of Japanese Studies at the Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences. "That part of history was basically in oblivion in the memories of many Japanese before the 1980s. So it's very difficult for the war orphans to live a decent life back in Japan."

Liu experienced a down period, taking as many part-time jobs as she could. But a tough woman, she managed to lead a happy life with her big family.

A monument dedicated to Chinese foster parents at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province. Over 1,000 Japanese war orphans donated money to build the monument in 1999. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Before our trip to Fangzheng, we arrived at Daqing, known as the oil city, to visit her Chinese brother Liu Changmao who's in his 70s now. They'd written to each other a few times every month before smartphones facilitated video communication.

"We are very close. My parents died when I was only six, my Japanese sister helped bring me up when we lived at our relatives' home in Shandong," Liu Changmao said. "Stay home. COVID-19 is rampant in Japan," he told his Japanese sister before hanging up.

In Japan, Liu Guizhi and other Japanese war orphans, have been helping to improve China-Japan ties – a relationship of entanglement imbued with love and hatred. In 2009, the elderly woman went to Beijing with a delegation of Japanese orphans and sang a song written by her Chinese husband to then Premier Wen Jiabao "China is my home forever."

In times of bilateral uncertainties, the orphans served as a bridge. In 1995, an orphan built a monument to Chinese foster parents in the China-Japan Friendship Garden – a cemetery then Premier Zhou Enlai ordered to construct in the 1960s in the memory of the over 5,000 Japanese who died in Fangzheng during their retreat. In 1999, over 1,000 orphans donated money to build another monument to Chinese foster parents inside the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang. There's also a China-Japan Amity House in Changchun, built exclusively to house elderly foster parents, which has remained empty since the last foster parent there died in late 2020.

"When the war orphans decided to go back to Japan, which recorded spectacular economic growth in the '80s and '90s, all their Chinese parents showed was encouragement no matter how reluctant they were," Meng said.

Du has been studying the population of Chinese parents who adopted Japanese orphans. According to her observation, these parents would always let the children choose their own path, even though some of them did not choose to have their own kids in order to create a better environment for the children of the enemy. "Children are innocent. They are also victims to the war."

For Liu Guizhi, Xu Shilan, Sun Yuqin, and others like them, the war is still very much part of their lives. Sometimes, Xu would stare at the smallpox vaccination scar on her left arm, which is different from the one for the Chinese, and the only mark her native country has left on her.

(Special thanks to the following people, in addition to the interviewees mentioned in the article, who helped tremendously with our reporting, offering their expertise and resources: Da Zhigang director and research fellow of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at the Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences, Lv Xiang, a retired professor of studies of Japan and Korea at the Liaoning Academy of Social Sciences, and Guo Xiangsheng, a folklore researcher in Fangzheng.)

Reporters: Wang Xiaonan, Bi Junxin

Writer: Wang Xiaonan

Video editor: Zhao Yue

Videographer: Qi Jianqiang

Yu Jing helped with video editing.

Cover image designer: Li Jingjie

![[Battle-Of-Bhamo_December-1944]_Sun Liren (first person from the right), U.S Commander Solden ...jpg [Battle-Of-Bhamo_December-1944]_Sun Liren (first person from the right), U.S Commander Solden ...jpg](https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/data/attachments/84/84810-52bc9acceb2eb14ef6ae0a7cec6f3608.jpg)

![[Battle-Of-Shanghai, 1937]_Chinese_Soldiers.jpg [Battle-Of-Shanghai, 1937]_Chinese_Soldiers.jpg](https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/data/attachments/84/84812-57f6b89964576c4689cbff53c1dc72b1.jpg)