You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

WW II Historical Thread, Discussion, Pics, Videos

- Thread starter Jeff Head

- Start date

Just remember everyday, the survivors are diminishing due to age. It's up to us younger generation to remember what happened, and past that knowledge tobthe next generation. Particularly when the Japs are in denials.

From Xinhua:

"70 survivors of the Nanjing Massacre passed away this year, reduced the total number of registered survivors to 65.

The Nanjing Massacre took place on Dec. 13, 1937. Over six weeks, about 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers were killed"

From Xinhua:

"70 survivors of the Nanjing Massacre passed away this year, reduced the total number of registered survivors to 65.

The Nanjing Massacre took place on Dec. 13, 1937. Over six weeks, about 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers were killed"

If we don't learn from history, we are liable ti repeat it. Least we forget.

I've seen this photo before and now I know her name-rest in honoured peace heroine-may we never forget her sacrifice and so very many others who suffered and died but China /Chinese ultimately triumphed.Least we forget. She could easily have been my aunty or anyone's aunty. Brave hero's of our continue struggle for freedom and liberty.

We mustn't forget their sacrifices, and the facts that the Japanese still haven't atone for their atrocities.

Chinese guerrilla fighter Cheng Benhua smiling moment before execution by the Japanese. (Late 1938)

She led a local resistance movement during the Nanjing Massacre, was then imprisoned and gang raped before being executed by bayonet. This photo is the primary reason she is remembered.

View attachment 74989

BTW-I IIRC a old book (of which I am still looking for as my own copy) is Frank Dorn's "Sino-Japanese War-1937-1941"One of the best books on the early start of WW2 -not Poland 1939-she was described as a "Chinese guerilla fighter caught by Japanese Army during the 3-All Campaign in Northern China after the fall of Nanjing-fate unknown" I knew by looking at her sad,wistful,resigned face she knew what awful fate was in store for her( I won't lie and hope to be 1/10 as brave as her!).The leering ,bestial Japaanese soldiers sitting behind her were of course slavering animals waiting to fall upon her like starving monsters that they were.(I hope they burn in hell)BTW is there any good articles or books on IJA's 3-All campaign(Sanko)??And I believe that the famous Japanese General tomoyuki Yamashita -who headed the 3All Campaign and various "Bandit Pacification Campaigns" stole alot of gold from North China and hid it in the Philipines-which could have been found by Ferdinand Marcos ex-Japanese Army officers who used it to rebuild war torn Japan and enrich Marcos.I've seen this photo before and now I know her name-rest in honoured peace heroine-may we never forget her sacrifice and so very many others who suffered and died but China /Chinese ultimately triumphed.

Hendrik_2000

Lieutenant General

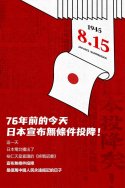

China commemorate the 76th surrender of Japanese army in WWII . they arrogantly said that they will finish the war in 3 months But 14 years latter they still fight. Tribute to the indominable spirit of Chinese people

Various event was held to commemorate win over fascist army and honor martyr

Various event was held to commemorate win over fascist army and honor martyr

Last edited:

Hendrik_2000

Lieutenant General

Old allies China and Russia celebrate the V days with commemorative event Russia alone among the white nation help China to resist the war against Japan by providing heavy gun, ammunitions, plane , tank. MG, Pilot ,training. Allowing the war to drag on for 14 years pin down and sapped IJA strength. Eternal gratitude! But western media seldom mention China's role and sacrifice in WWII

The communist play a secondary role understandably so since they are under armed and just come from bruising fight with the KMT. But they do fight in legendary battle of Taihang mountain

China, Russia jointly celebrate V-Day amid shared WWII view and need to counter Japanese aggressive resurgence

By

Published: Sep 03, 2021 04:08 PM

To mark the 76th victory anniversary of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), China and Russia - two major contributors to wining WWII - jointly held memorial activities, which analysts said intends to urge Japan to truly reflect on its military mistakes instead of binding itself increasingly tighter with the US and endangering regional peace and stability. This is the latest and vivid example of the highly accordant values and mutual trust shared by China and Russia.

Forgive but never forgot!

"From the September 18 incident in 1931, the beginning of Japan's invasion of China, to Japan's surrender in 1945, the Chinese people had experienced an extremely hard and bitter fight. We commemorate V-Day every year not only to mourn those who sacrificed but also to remember the history and to cherish the current peace," a netizen named "chuanggezi" wrote.

The Chinese people had fought hard to win the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression during the 14 years from 1931 to 1945 with more than 35 million Chinese soldiers and civilians dead, accounting for nearly 8 percent of China's population in 1928. It is the main battlefield against Japanese fascism before the Pacific War (1941-1943), Japan deployed about 80-94 percent of its troops in China during the period.

Battle of Taihang mountain

Story told by Xi Soviet Pilot help China

China resists Japanese aggression

The communist play a secondary role understandably so since they are under armed and just come from bruising fight with the KMT. But they do fight in legendary battle of Taihang mountain

China, Russia jointly celebrate V-Day amid shared WWII view and need to counter Japanese aggressive resurgence

By

Published: Sep 03, 2021 04:08 PM

To mark the 76th victory anniversary of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), China and Russia - two major contributors to wining WWII - jointly held memorial activities, which analysts said intends to urge Japan to truly reflect on its military mistakes instead of binding itself increasingly tighter with the US and endangering regional peace and stability. This is the latest and vivid example of the highly accordant values and mutual trust shared by China and Russia.

Forgive but never forgot!

"From the September 18 incident in 1931, the beginning of Japan's invasion of China, to Japan's surrender in 1945, the Chinese people had experienced an extremely hard and bitter fight. We commemorate V-Day every year not only to mourn those who sacrificed but also to remember the history and to cherish the current peace," a netizen named "chuanggezi" wrote.

The Chinese people had fought hard to win the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression during the 14 years from 1931 to 1945 with more than 35 million Chinese soldiers and civilians dead, accounting for nearly 8 percent of China's population in 1928. It is the main battlefield against Japanese fascism before the Pacific War (1941-1943), Japan deployed about 80-94 percent of its troops in China during the period.

Battle of Taihang mountain

Story told by Xi Soviet Pilot help China

China resists Japanese aggression

Last edited:

Japanese war orphans adopted by the Chinese.

"China is my home now!"

Feature 19:47, 18-Sep-2021

The bond: Japanese war orphans and their Chinese parents

Updated 20:14, 18-Sep-2021

, Zhao Yue

06:27

When Xu Shilan was little, she asked her father which date she was born on after seeing other kids celebrate their birthdays. Her father paused, then uttered, "July 20 is your lunar birthday."

Years later she learned that July 20 on the lunar calendar is in fact August 15 in the year of 1945, the day Japan surrendered to the Allies, bringing an end to WWII. She recounted this childhood memory, sitting on her bed in a cozy bungalow opening to a backyard studded with mottled pots of flowers.

We made the visit to her home in the northeastern Chinese town of Fangzheng, 120 miles away from the capital city of Harbin in Heilongjiang Province. Upon arriving, she was already waiting for us, dressed in a claret-red coat and her neatly combed jet black hair, which her daughter said she had helped dye. It's hard to tell her exact age from her wrinkled face and diminishing hearing, yet she was able to articulate her thoughts clearly. She believes she's 80 years old, but there's no way to be sure, since her father had her age set at 19 in the year she got married.

She'd lived a peaceful life with her family – a loving husband and three children – until one day in the year 2000 when she came across a man who was surprised to see her and asked, "Why are you still in town? They've already gone back to Japan." That statement made her realize why she had been called "little Jap" by neighboring kids when she was little.

The man turned out to have handed her over to her foster parents in the final days of WWII. At the time, he encountered a feeble Japanese woman in the street who had begged him to take care of her baby girl. A poor 19-year-old himself, he couldn't afford to raise a child and hence went searching for a kindhearted family to take her in. Finally the toddler, groaning with fever and pain, was rescued by a young couple. "Your foster father repeatedly warned me against telling that you are a Japanese orphan," the man told Xu, a promise that he kept for over half a century.

A map shows the Japanese settlements after the Japanese invasion in northeast China started on September 18, 1931. Photo taken at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021. Qi Jianqiang/CGTN

In those days of turmoil following the war that had begun with the Japanese invasion on September 18, 1931, Chinese foster families chose to keep secret their adoption of Japanese children, afraid that a target would be painted on the backs of these young lives. After all, they were the children of the enemy.

Sun Yuqin, who lives a 30-minute drive away from Xu, only came to know that she's Japanese when her foster mother was dying in 1968.

"When I was seven, a neighbor – a Japanese woman known as a 'stranded war wife' – told me I'm Japanese. I ran home seeking confirmation from my mother. My mother said, 'No, you are definitely Chinese'," Sun, now 76, told us. Unlike Xu, she knew how old she was because she was born in her foster parents' home.

In the days shortly before Japan's defeat, Sun's biological mother was about to give birth and hid along with her father in a cornfield behind what was back then her Chinese parents' house. "My foster family found them and let them in the house since my birth mother's amniotic fluid broke in a gush. Days later, my foster mother delivered me. By then news came that Japan had surrendered and my biological parents left in spite of persuasion," Sun said. "After finding my biological parents dead in a battle, my foster family realized they must protect and bring me up."

Sun showed us the mark on her right leg – the scar of a scratch left by her birth mother, along with a brown tweed coat and a letter with their family information in it. Sun wore that coat for decades before turning it into a smaller jacket for her grandson. As for the letter, she found it in an embroidered shoe according to the clue her foster mother offered. It's now become a mess of erasures and stains after all these years.

A street scene in Fangzheng County, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China, April 29, 2021. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Adopting the enemy's children

Xu and Sun are the only Japanese war orphans who are still alive in Fangzheng, the quiet, scarcely populated county in China peppered with billboards in both the Chinese and Japanese languages. The small town's complicated ties with Japan date back to September 18, 1931.

With the Japanese invasion of northeast China came an emigration program to settle 1 million Japanese households, roughly 5 million people, in northeast China over the following 20 years, as part of Japan's effort to colonize the fertile, resource-rich region. "Officials, factory managers, railway workers, and mostly, farmers, came in throngs with the creation of the puppet state known as Manchuria. First the men arrived, then the women followed, with families right behind, turning Chinese villages into Japanese communities," Meng Yueming, deputy director of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at the Shenyang Academy of Social Sciences, explained. "Many rural Japanese were deceived by the Japanese government at the time who had promised them a better life and land possession."

Japan sent over 380,000 agrarian emigrants, most of them living a destitute and depressed life in rural Japan. In northeastern China, they tilled the land the Japanese army confiscated from Chinese peasants and also hired Chinese as laborers. In a way, they developed sophisticated relationships with the locals, filled with a mixture of agony, hatred and sympathy. Fangzheng was home to a large number of such Japanese settlements. Xu said her foster father utterly detested them as he was badly beaten by some Japanese while working for them.

In the final years of WWII, male Japanese farmers were conscripted and became part of the Japanese army reserve to help fight its war, leaving behind women, children and the elderly.

In August 1945, Japan surrendered as the Soviet army advanced. An exodus began.

"China is my home now!"

Feature 19:47, 18-Sep-2021

The bond: Japanese war orphans and their Chinese parents

Updated 20:14, 18-Sep-2021

, Zhao Yue

06:27

When Xu Shilan was little, she asked her father which date she was born on after seeing other kids celebrate their birthdays. Her father paused, then uttered, "July 20 is your lunar birthday."

Years later she learned that July 20 on the lunar calendar is in fact August 15 in the year of 1945, the day Japan surrendered to the Allies, bringing an end to WWII. She recounted this childhood memory, sitting on her bed in a cozy bungalow opening to a backyard studded with mottled pots of flowers.

We made the visit to her home in the northeastern Chinese town of Fangzheng, 120 miles away from the capital city of Harbin in Heilongjiang Province. Upon arriving, she was already waiting for us, dressed in a claret-red coat and her neatly combed jet black hair, which her daughter said she had helped dye. It's hard to tell her exact age from her wrinkled face and diminishing hearing, yet she was able to articulate her thoughts clearly. She believes she's 80 years old, but there's no way to be sure, since her father had her age set at 19 in the year she got married.

She'd lived a peaceful life with her family – a loving husband and three children – until one day in the year 2000 when she came across a man who was surprised to see her and asked, "Why are you still in town? They've already gone back to Japan." That statement made her realize why she had been called "little Jap" by neighboring kids when she was little.

The man turned out to have handed her over to her foster parents in the final days of WWII. At the time, he encountered a feeble Japanese woman in the street who had begged him to take care of her baby girl. A poor 19-year-old himself, he couldn't afford to raise a child and hence went searching for a kindhearted family to take her in. Finally the toddler, groaning with fever and pain, was rescued by a young couple. "Your foster father repeatedly warned me against telling that you are a Japanese orphan," the man told Xu, a promise that he kept for over half a century.

A map shows the Japanese settlements after the Japanese invasion in northeast China started on September 18, 1931. Photo taken at the September 18th History Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, April 26, 2021. Qi Jianqiang/CGTN

In those days of turmoil following the war that had begun with the Japanese invasion on September 18, 1931, Chinese foster families chose to keep secret their adoption of Japanese children, afraid that a target would be painted on the backs of these young lives. After all, they were the children of the enemy.

Sun Yuqin, who lives a 30-minute drive away from Xu, only came to know that she's Japanese when her foster mother was dying in 1968.

"When I was seven, a neighbor – a Japanese woman known as a 'stranded war wife' – told me I'm Japanese. I ran home seeking confirmation from my mother. My mother said, 'No, you are definitely Chinese'," Sun, now 76, told us. Unlike Xu, she knew how old she was because she was born in her foster parents' home.

In the days shortly before Japan's defeat, Sun's biological mother was about to give birth and hid along with her father in a cornfield behind what was back then her Chinese parents' house. "My foster family found them and let them in the house since my birth mother's amniotic fluid broke in a gush. Days later, my foster mother delivered me. By then news came that Japan had surrendered and my biological parents left in spite of persuasion," Sun said. "After finding my biological parents dead in a battle, my foster family realized they must protect and bring me up."

Sun showed us the mark on her right leg – the scar of a scratch left by her birth mother, along with a brown tweed coat and a letter with their family information in it. Sun wore that coat for decades before turning it into a smaller jacket for her grandson. As for the letter, she found it in an embroidered shoe according to the clue her foster mother offered. It's now become a mess of erasures and stains after all these years.

A street scene in Fangzheng County, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China, April 29, 2021. Wang Xiaonan/CGTN

Adopting the enemy's children

Xu and Sun are the only Japanese war orphans who are still alive in Fangzheng, the quiet, scarcely populated county in China peppered with billboards in both the Chinese and Japanese languages. The small town's complicated ties with Japan date back to September 18, 1931.

With the Japanese invasion of northeast China came an emigration program to settle 1 million Japanese households, roughly 5 million people, in northeast China over the following 20 years, as part of Japan's effort to colonize the fertile, resource-rich region. "Officials, factory managers, railway workers, and mostly, farmers, came in throngs with the creation of the puppet state known as Manchuria. First the men arrived, then the women followed, with families right behind, turning Chinese villages into Japanese communities," Meng Yueming, deputy director of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at the Shenyang Academy of Social Sciences, explained. "Many rural Japanese were deceived by the Japanese government at the time who had promised them a better life and land possession."

Japan sent over 380,000 agrarian emigrants, most of them living a destitute and depressed life in rural Japan. In northeastern China, they tilled the land the Japanese army confiscated from Chinese peasants and also hired Chinese as laborers. In a way, they developed sophisticated relationships with the locals, filled with a mixture of agony, hatred and sympathy. Fangzheng was home to a large number of such Japanese settlements. Xu said her foster father utterly detested them as he was badly beaten by some Japanese while working for them.

In the final years of WWII, male Japanese farmers were conscripted and became part of the Japanese army reserve to help fight its war, leaving behind women, children and the elderly.

In August 1945, Japan surrendered as the Soviet army advanced. An exodus began.