I agree that a crisis that clearly and publicly demonstrates the shifting balance of power can act to short-cut the psychological adaptation process, but even then the story is far from complete. For example, while many Americans today are willing to acknowledge China's growing power in the world, they also tend to frame this in terms of particular domestic policy choices that are enabling China, or holding America back or somesuch. The notion that China's rise is something that is fundamentally outside America's control, the idea that the self-described greatest country in the world might be surpassed and that there is nothing that can be done to prevent it, is entirely too bitter a pill for most Americans to swallow at this point. It's that deeper adaptation that will require generations I think, and it's not really about China at all, but about Americans and how they see themselves and their nation.

This is possibly verging too far from the original topic, but I think the question of how nations and civilisations cope psychologically with significant shifts in power is a very interesting one, from the self-assured myths that are created when nations are at the apex of their power (e.g. US, China, UK, Spain, etc.), to the denial and anxiety of nations in decline (e.g. Russia) to the reactions when old certainties are shaken (reform, revolution, fundamentalist religion). Patrick Smith's book "Time No Longer: Americans after the American Century" is a good work in this area.

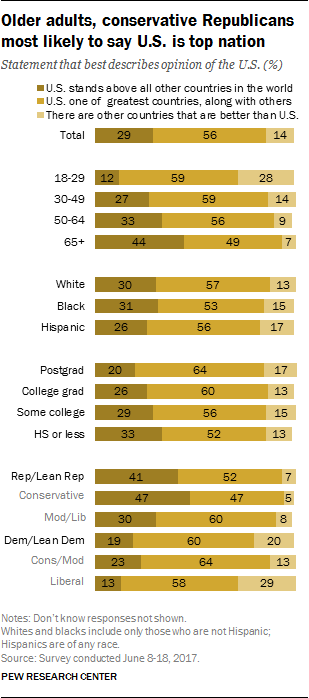

You can see the difference in views when you look at age.

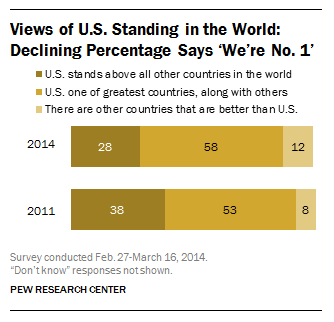

In 2017, almost half (44%) of Americans over 65 think the US is exceptional.

In comparison, only 1 in 8 people (12%) under 30 think so.

So yes, it will still take some time until the majority of Americans accept the US is not exceptional.

Last edited: