Boeing is confident it can win the Navy’s

. In fact, it’s so bullish that it may already be on a path to building a second prototype.

During a March 6 visit to St. Louis, Defense News got to be the first media outlet to see the company’s MQ-25 offering up close and personal.

Asked if Boeing Phantom Works was working on a second MQ-25 prototype after having revealed the first one in December, its program director Don “BD” Gaddis and capture lead Dave Thieman laughed and pointedly steered the conversation in a different direction.

But another source indicated that another MQ-25 prototype could be revealed in short order.

It wouldn’t be the first time that Boeing has poured its investment dollars into creating not only one, but two test versions of an aircraft while a competition still rages on. In 2016, the company

in a glitzy ceremony, and then 15 minutes later took reporters to a nearby hanger to reveal a second aircraft going through tests.

If a second Boeing MQ-25 exists, it’s evidence of how badly the company wants to win the competition, which has been narrowed down to three vendors — Boeing, General Atomics and Lockheed Martin — after

.

“This is a high-priority program,” said Phil Finnegan, a unmanned system analyst at the Teal Group. “They’re really intent on strengthening their position in unmanned systems.”

Boeing has poured its own money into maturing its carrier-based drone concept and is the first of the three vendors to make its MQ-25 air vehicle public.

Its Phantom Works division conducted the initial design review for what became its MQ-25 prototype in October 2012, back when the U.S. Navy was still pursuing an unmanned aircraft that could fly on and off the carrier to conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance as well as strike missions, under a program called Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike, or UCLASS, Gaddis said.

The company quietly rolled out the prototype within the company in November 2014, just a month before the Navy announced it was pausing the UCLASS program.

“You can imagine how upset we were,” laughed Thieman.

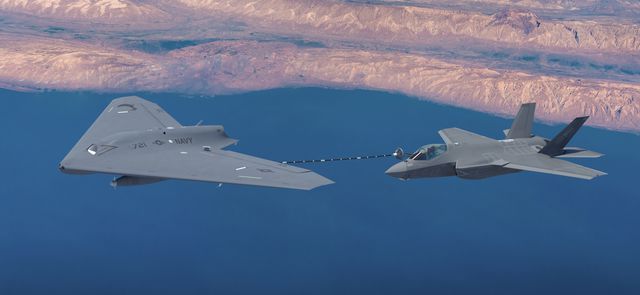

Then, in 2016, the Navy killed UCLASS and began a new carrier drone program called Carrier-Based Aerial-Refueling System, or CBARS, which later became the MQ-25. Instead of an ISR and strike mission, the MQ-25 would act as an autonomous, unmanned tanker and relieve F/A-18E/F Super Hornets from refueling duties that take away from the fighters’ core mission set.

But Boeing found that its UCLASS design was already a good fit for the tanking mission. Unlike Northrop, which invested heavily in a stealthy, flying-wing design aimed at a precision-strike mission, Boeing opted for a wing-body-tail air vehicle with limited low-observable features and a large payload bay.

“One of the things that people should be reminded of is that in UCLASS, tanking was one of the missions for UCLASS, and the company designed the airplane around that mission area as well as all of the other UCLASS mission areas,” Gaddis said. “So the other UCLASS missions are gone, but the tanking still remains, and we feel that this aircraft is right in the wheelhouse of that tanking requirement.”

Externally, Boeing’s MQ-25 prototype, also known as T1, is still the same as its UCLASS design. However, the company had to do significant rework on the mission systems side as the requirement shifted from surveillance to refueling.

“There will be some touches in the airplanes between T1 and [the first engineering and manufacturing development, or EMD, aircraft], but not many. The biggest change are in the mission systems,” Gaddis said. “The UCLASS requirements are quite different than the MQ-25 requirements for mission systems. And so when you go from big ISR to little ISR, that’s really the biggest change for MQ-25.”

Jerry Hendrix, a retired Navy captain and defense analyst at the Center for a New American Security, said Boeing’s prototype shows its UCLASS origins, with a large, robust fuselage “boat” that could carry fuel or — as originally developed — advanced sensor systems and ordnance.

“One area of concern, however, is the thin wing design, which is clearly influenced by the previous high-altitude ISR mission,” he said.

“I would expect, as the MQ-25 mission tanker program goes forward, that this prototype would evolve the wings to make them wider from their front leading edge to back and also thicker. This would make the platform more robust for sustained tanking missions as well as add additional fuel capacity to the design.”

As

has noted, Boeing’s design features a flush dorsal jet intake that supplies air to the engine, which as of yet has not been specified by the company. According to Gaddis, the company’s MQ-25 stores its fuel in tanks surrounding the engine, and the inner section of its fold-up wings are “wet,” meaning the fuel moves freely within that part of the wing.

According to the Navy’s requirements, the MQ-25 must be able to deliver 14,000 pounds of fuel at distances of 500 nautical miles from an aircraft carrier.

Gaddis said Boeing’s design meets that requirement with margin to spare, telling Defense News that it “carries a ton of gas.” But with a competition still ongoing, he declined to detail exactly how much the air vehicle can carry.

The Navy will decide the MQ-25 competition in August, choosing a single vendor and awarding a contract for the four EMD aircraft, with an option for three more test assets.

In its fiscal 2019 budget request, the Navy announced that it would begin production in FY23 with a procurement of four drones, ahead of an initial operational capability in FY26. It plans to buy 72 aircraft over the course of the program.

Boeing should be ready for the first flight of its MQ-25 shortly after the Navy makes its downselect decision in August, but it still has a lot of work to do before then, Gaddis said.

Besides moving its prototype through the standard testing process that all aircraft go through before first flight, it also needs to finish its statement of work. Boeing — like the other competitors — was awarded a contract to refine its MQ-25 concept, which includes activities such as software integration and improving its open-systems architecture.

It also includes providing data about how to handle the drone aboard the deck of an aircraft carrier, which Boeing is demonstrating through a series of drills in St. Louis, Missouri. The company mapped out the deck of an aircraft carrier on the tarmac at Lambert Field, and Boeing employees have practiced how to safely and efficiently move its MQ-25 around the ship by taxiing it around, tested the arresting gear and hooking it into a catapult.