"The National Shipbuilding Strategy made the recommendation that the MoD replace the ships once they reach their first refit period, rather than extending their time in service thorough costly refits, meaning that Type 31es could be sold while still relatively new and replaced with more modern incrementally upgraded examples all while clawing back some of the money used to build them with overseas sales.

The idea behind this being that ships have a 15 year life span, rather than the 30 or so they usually would, meaning they are sold on at mid-life refit time. Doing this would maintain relatively constant production of the Type 31e, similar to the Arleigh Burke class in the United States which has now been in build for decades with each batch being superior to the last."

This was of course the same as the original plan for the Type 23 class frigates, which had a 'design' life of 18 years, the idea being to force the government into a continuous rolling building programme of one frigate a year, and meant the vast sums spent on mid life refits could be channelled into new purpose built designs better able to accommodate new weapons and sensors. A very sensible idea. Which of course the Government weaselled their way out of and which lead to the very expensive but very necessary type 23 mid life update refits currently underway. Similarly HMS Ocean was always said to have a twenty year life span because the plan was to force the government into building a more up to date replacement without having to spend money on a big refit. Which they did anyway (about four years ago, extending her life way beyond 2018).

It's a good plan, not new, failed last time because the pollies screwed it up. Just waiting to see how they screw it up this time...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Jura The idiot

General

"This was of course the same as the original plan for the Type 23 class frigates, which had a 'design' life of 18 years, the idea being to force the government into a continuous rolling building programme of one frigate a year, and meant the vast sums spent on mid life refits could be channelled into new purpose built designs better able to accommodate new weapons and sensors. A very sensible idea. Which of course the Government weaselled their way out of and which lead to the very expensive but very necessary type 23 mid life update refits currently underway. Similarly HMS Ocean was always said to have a twenty year life span because the plan was to force the government into building a more up to date replacement without having to spend money on a big refit. Which they did anyway (about four years ago, extending her life way beyond 2018).inside:

It's a good plan, not new, failed last time because the pollies screwed it up. Just waiting to see how they screw it up this time..."

if it's "a good plan" it depends on the original design,

and who on Earth (except a ship scrapping company) would pay for an oversized OPV

Jun 1, 2018

Yesterday at 8:19 PM

I wonder what the armament of this 'whopper'

("... with a displacement of approximately 5,700 tonnes ..." )

would be; I've read somewhere 1 m of the hull = 1 m Pounds, I'll leave it at that

which cost $300m fifteen plus years ago, this price including, cough cough, weaponry?!

not sure if any Navy of the World would want such a vessel even if donated

timepass

Brigadier

UK considers options for possible off-the-shelf Harpoon replacement...

The United Kingdom may look to acquire an off-the-shelf surface-to-surface guided weapon (SSGW) to bridge the gap between the retirement of Harpoon and the planned introduction of a Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon (FC/ASW).

Providing evidence on 11 July to the joint UK House of Commons Defence Committee/French National Assembly inquiry for the FC/ASW programme, senior Ministry of Defence (MoD) officials confirmed that market survey activity was already under way.

All 13 Royal Navy (RN) Type 23 frigates and three out of six Type 45 destroyers are fitted with the GWS 60/Harpoon Block 1C SSGW. The system, procured in the 1980s under Staff Requirement (Sea) 6548, had originally been planned to retire at the end of 2018, but the life of the weapon has now been extended to 2023.

Intended to enter service in the 2030 timeframe, the FC/ASW is currently the subject of a three-year concept phase activity, jointly funded by the French and UK governments, being led by MBDA. The United Kingdom is in parallel looking at several off-the-shelf options as part of the concept phase to be informed of other potential solutions.

Giving evidence to the joint committee hearing, Defence Equipment and Support Chief Executive Simon Bollom said that any further Harpoon life extension would be difficult. “The biggest challenges with this weapons system are the energetics, the propulsion system, and the warhead,” he said. “Here we come to difficult issues with finite lives and, clearly, its chemical compounds. Our assessment at this stage is that going beyond 2023 would be a challenge.”

According to Lieutenant General Mark Poffley, deputy chief of the Defence Staff (Military Capability), a new SSGW has assumed a higher priority inside the equipment programme. “We know we would like a surface-to-surface weapon. We have got some choices to make about where it might come from, and we know there is a lot of pressure on the rest of the budget.

The United Kingdom may look to acquire an off-the-shelf surface-to-surface guided weapon (SSGW) to bridge the gap between the retirement of Harpoon and the planned introduction of a Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon (FC/ASW).

Providing evidence on 11 July to the joint UK House of Commons Defence Committee/French National Assembly inquiry for the FC/ASW programme, senior Ministry of Defence (MoD) officials confirmed that market survey activity was already under way.

All 13 Royal Navy (RN) Type 23 frigates and three out of six Type 45 destroyers are fitted with the GWS 60/Harpoon Block 1C SSGW. The system, procured in the 1980s under Staff Requirement (Sea) 6548, had originally been planned to retire at the end of 2018, but the life of the weapon has now been extended to 2023.

Intended to enter service in the 2030 timeframe, the FC/ASW is currently the subject of a three-year concept phase activity, jointly funded by the French and UK governments, being led by MBDA. The United Kingdom is in parallel looking at several off-the-shelf options as part of the concept phase to be informed of other potential solutions.

Giving evidence to the joint committee hearing, Defence Equipment and Support Chief Executive Simon Bollom said that any further Harpoon life extension would be difficult. “The biggest challenges with this weapons system are the energetics, the propulsion system, and the warhead,” he said. “Here we come to difficult issues with finite lives and, clearly, its chemical compounds. Our assessment at this stage is that going beyond 2023 would be a challenge.”

According to Lieutenant General Mark Poffley, deputy chief of the Defence Staff (Military Capability), a new SSGW has assumed a higher priority inside the equipment programme. “We know we would like a surface-to-surface weapon. We have got some choices to make about where it might come from, and we know there is a lot of pressure on the rest of the budget.

The 'Good Plan' refers to keeping the shipyards in work and supplying the RN with a steady stream of up to date ships which as they approach obsolescence are replaced by newer up to date ships, and then the older ones provide second and third tier navies with second hand warships that are by no means clapped out and fit only for scrap. I was referring to the type 23s where the plan originated, and now it is being revived for the type 31e, which in itself is supposed to be attractive as an export design even when new build. Getting the design right in the first place is where we are at now, and once again the politicians are getting in the way."This was of course the same as the original plan for the Type 23 class frigates, which had a 'design' life of 18 years, the idea being to force the government into a continuous rolling building programme of one frigate a year, and meant the vast sums spent on mid life refits could be channelled into new purpose built designs better able to accommodate new weapons and sensors. A very sensible idea. Which of course the Government weaselled their way out of and which lead to the very expensive but very necessary type 23 mid life update refits currently underway. Similarly HMS Ocean was always said to have a twenty year life span because the plan was to force the government into building a more up to date replacement without having to spend money on a big refit. Which they did anyway (about four years ago, extending her life way beyond 2018).

It's a good plan, not new, failed last time because the pollies screwed it up. Just waiting to see how they screw it up this time..."

if it's "a good plan" it depends on the original design,

and who on Earth (except a ship scrapping company) would pay for an oversized OPV

Jun 1, 2018

which cost $300m fifteen plus years ago, this price including, cough cough, weaponry?!

not sure if any Navy of the World would want such a vessel even if donated

Jura The idiot

General

OK I think now I know where our opinions differ (so LOL attaching 'Like'):The 'Good Plan' refers to keeping the shipyards in work and supplying the RN with a steady stream of up to date ships which as they approach obsolescence are replaced by newer up to date ships, and then the older ones provide second and third tier navies with second hand warships that are by no means clapped out and fit only for scrap. I was referring to the type 23s where the plan originated, and now it is being revived for the type 31e, which in itself is supposed to be attractive as an export design even when new build. Getting the design right in the first place is where we are at now, and once again the politicians are getting in the way.

I think 5+k tons displacing warship can't be procured for about $300m (I mean a real warship, no or other tricks played),

and she wouldn't be "attractive" in any way

(of course it's different for the Type 23 or for the Ocean you mentioned previously)

Not sure if it is the correct thread - most likely not - but since we don't have a dedicated modelling section yet I post it here:

Simply amazing.

Deino

@Jeff Head

Fleet of fancy! Modeller spent 70 years and used over a MILLION matchsticks to create all 484 warships to ever sail in the Royal Navy since 1945 including HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier

- Master modeller Philip Warren has spent 70 years building an incredible fleet of 484 warships from matches

- The 87-year-old has painstakingly hand made the whole armada using using just a ruler, razor blade and glue

- The impressive collection has even caught the eye of some of the royals, in the 1980s he presented a model of the HMS Cumberland to Prince Andrew at Broughton Airfield

Simply amazing.

Deino

@Jeff Head

Seen this many times...and high res, and several pics showing the whole fleet.Not sure if it is the correct thread - most likely not - but since we don't have a dedicated modelling section yet I post it here:

Simply amazing.

Deino

@Jeff Head

My own fleet consists of about 75 ships,

70 are modern with seven carriers, three of which are US.

I have Five World Wr II ships two of which are carriers.

As to the Type 23, with their new upgrades they are going to be extremely effective for a numbr of years...any Navy would fine a good 15-20 years use of them even after the UK sells them off once acquiring the new Frigates.

Jura The idiot

General

Jun 19, 2018

HMS Tyne returns to service after being paid off in May

tragicomic, also the status of that OPV guarding the Falklands

now (dated July 31, 2018)who'd post if not me

UK Royal is reactivating Offshore Patrol HMS P281 - only decommissioned May 24 (!) - as problems with new OPV P222 (commissioned April 13) are more serious than thought. SEVERN P282, decom'ed last October, refitting as well.

HMS Tyne returns to service after being paid off in May

tragicomic, also the status of that OPV guarding the Falklands

Jura The idiot

General

Mar 20, 2017

"HMS Defender has not yet received the major Propulsion Improvement Package (PIP) which is scheduled to begin with the first Type 45 next year."

HMS Defender returns to the fleet fitted for intelligence gathering

now (dated August 7, 2018)for those who remember Feb 6, 2016

Type 45 Destroyers:Written question - 67575

Q

Asked by

(Portsmouth South)

Asked on: 13 March 2017

"To ask the Secretary of State for Defence, when he plans to award contracts for the Power Improvement Project for the Type 45 destroyer class."

A

Answered by:

Answered on: 16 March 2017

"On current plans, we anticipate that the Ministry of Defence will be able to award the contract for the Power Improvement Project for the Type 45 Destroyer class in early 2018."

(related, dated May 2016 though:

Project Napier sees twin-track plan adopted to resolve Type 45 problems

vaporware?

"HMS Defender has not yet received the major Propulsion Improvement Package (PIP) which is scheduled to begin with the first Type 45 next year."

HMS Defender returns to the fleet fitted for intelligence gathering

Jura The idiot

General

Nov 20, 2017

How will the UK MoD pay for Trident in an era of funding gaps?

6 August 2018

soNov 6, 2017

sorta related:

noticed in Twitter:

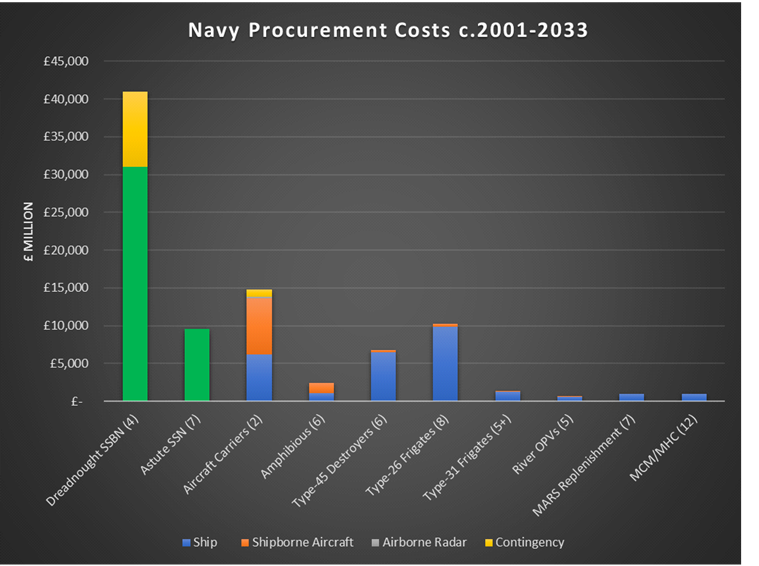

Yes they are very complex, but why are 4 SSBNs going to cost around 4 x that of 7 Astute class submarines? chart via

Trident submarine plans facing a ‘perfect storm’ of problems, says MoD report

19th November

How will the UK MoD pay for Trident in an era of funding gaps?

6 August 2018

The UK National Audit Office expects the total cost of the Trident nuclear submarine programme to hit £50.9bn – £2.9bn over budget – on top of the £3bn the MoD has already had to find in efficiency savings. Julian Turner asks how further cutbacks can be made without compromising Trident’s mission.

For anyone old enough to remember the Cold War in general – and the 1963 Cuban Missile Crisis in particular – the phrase ‘mutually assured destruction’ is likely to be indelibly etched on their psyche.

The concept is chillingly simple: if two opposing sides have sufficient nuclear weapons to annihilate the other, full-scale nuclear war will be avoided, as a pre-emptive strike by either would guarantee its subsequent destruction. It also means, of course, that neither nation has any incentive to disarm.

Until recently, talk of all-out nuclear war had, thankfully, all but disappeared from public discourse – yet, like the weapons that enforce it, the concept of mutually assured destruction remains in place.

For the past half-century, somewhere in the world, a British Vanguard-class submarine carrying up to 16 missiles, each armed with up to eight nuclear warheads, has been on patrol below the ocean’s surface. The logic goes that the vessel acts as a , because even if the nation’s conventional defences were destroyed, a submarine could still launch a catastrophic retaliatory strike on the aggressor.

“Our nuclear deterrent guarantees the defence of the UK, and it has done so successfully for more than half of my life and yours,” wrote Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in an open letter in 1986.

“To be effective, our deterrent has to be adequate to overcome the defences ranged against it.

“The Soviet Union has invested hugely in defence against ballistic missiles. It is now upgrading these defences further. If we are to retain the ability to penetrate them, we have to modernise our weapons systems. That was why we chose Trident. It will ensure that our deterrent remains effective well into the next century.”

Vanguard: renewing Britain’s nuclear deterrent

More than three decades later, the tense stand-off between the US and North Korea and concern about Iran’s nuclear programme have reignited the nuclear defence debate. In March, Prime Minister Theresa May reaffirmed the government’s commitment to maintaining the UK’s nuclear deterrent.

“The Chancellor of the Exchequer and I agreed the Ministry of Defence (MoD) will have access to £600m this coming financial year for the MoD’s Dreadnought submarine programme,” she said.

“Today’s announcement will ensure the work to rebuild the UK’s new world-class submarines remains on schedule and another sign of the deep commitment this government has to keeping our country safe.”

A final decision on the future of the Trident submarine fleet could not have waited much longer.

The current generation of four 150m-long Vanguard-class subs – Vanguard, Victorious, Vigilant and Vengeance – were introduced in 1994 and are due to be taken out of operation sometime in the late 2020s. The cost of replacing them with four new Dreadnought-class vessels is estimated to be £31bn.

Only one vessel is on patrol at any one time and work on a replacement could take up to 17 years.

Like its predecessors, the Dreadnought-class submarines will be equipped with multiple UGM-133A Trident II or Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Built by Lockheed Martin, they have a range of up to 7,500 miles. The subs will be the largest ever built for the Royal Navy, measuring 152.9m and with a displacement of 17,200 tonnes. They will cater for 130 crew, and manufacture their own oxygen and fresh water.

The £50.9bn price tag: can the MoD afford Trident?

However, funding the vast project is proving difficult. A recent report by the UK National Audit Office (NAO) reveals a significant shortfall in funding to renew and maintain the Trident nuclear deterrent.

Entitled ‘Equipment Plan 2017-2027’, the report puts the total projected cost of the Trident nuclear submarine project – designing, producing and maintaining the fleet of nuclear subs that carry warheads – at £50.9bn, £2.9bn more than the available Ministry of Defence (MoD) budget.

Around a quarter of the UK’s defence equipment budget to 2028 is earmarked for nuclear projects; this financial year, the MoD is expected to spend £1.8bn on procuring and supporting submarines.

The MoD has already taken £600m out of a £10bn contingency fund to pay for the Dreadnought programme and may be forced to go cap in hand to the Treasury again to plug the £2.9bn spending gap, the NAO warned.

“The coming years are crucial,” said Sir Amyas Morse, comptroller and auditor general of the NAO. “As the department invests heavily in the Dreadnought-class submarines and more widely across the enterprise, it needs to ensure that the new structures, processes and workforce operate effectively together to manage the £2.9bn affordability gap across the enterprise.”

The chair of the Commons Public Accounts Committee, Meg Hillier, commented: “The budget pressures on the MoD’s nuclear programme are significant. The department will need to make some critical decisions to get the programme on track financially.”

Are there viable alternatives to Trident?

The UK defence industry is already feeling the pinch. To fund the Vanguard replacement programme, the MoD has already had to find £3bn in efficiency savings over the next decade. Then there is the employment and brain drain dimension. Estimates suggest that up to 15,000 jobs – as well as significant expertise – may be lost if new submarines were not commissioned.

However, the NAO also flagged up skill shortages that need plugging across seven military sectors, with a need for 377 more skilled staff. that the MoD has developed new ways of working with key contractors such BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce on the Dreadnought programme in an effort to rectify past “poor performance”.

So, if the money can’t be found, what are the alternatives to Britain’s Trident nuclear deterrent in its current form?

The idea of using cruise missiles based on different subs with a far shorter range of around 1,000 miles was dismissed as even more costly, in terms of research and development, than renewing Trident. Cruise missiles, it was also pointed out, are also slower and more vulnerable to being shot down.

Other suggestions include a strategically located, land-based missile delivery system or launching missiles from a long-range aircraft. However, a 2013 options review again pointed to their shorter range and vulnerability, concluding that the idea needed “much more work”.

The Royal Navy has been committed to continuous at sea deterrence since April 1969. With military budgets under severe pressure, the UK Government may have to dig deeper into its pockets if the Trident nuclear deterrent is to be upgraded and maintained for a further 50 years.