China tries to justify its actions by asserting that it has sovereignty over the shoal, which it calls Huangyan Island. In April 2012, the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China published the basis of its claim to Bajo de Masinloc, through a paid advertisement in the local newspapers. In sum, China argues that it is entitled to Bajo de Masinloc on the ground that it first discovered the island, gave its name and incorporated it into its territory, and had always exercised jurisdiction over it. A serious examination of these grounds, however, bears out severe internal inconsistencies. Examination of the evidence shows the basis to be largely published fiction.

As to the claim of first discovery, China asserts that Chinese explorers discovered the shoal in the 13th century during the Yuan Dynasty. But the Yuan Dynasty was a foreign dynasty, established by Kublai Khan, and China was at the time merely part of the great Mongol Empire. If Bajo de Masinloc was indeed acquired by virtue of discovery, then such discovery could only be in the name of the sovereign, the Mongol Empire. Perhaps it should therefore be claimed by the remnant of the Mongol Empire, which is Mongolia, not China.

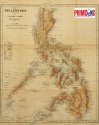

Be that as it may, as Justice Carpio points out and as seen on some of the maps in the exhibit, any ordinary person can see how tenuous this claim is. “Huangyan Island” never appears as such in any of the ancient maps of China, even after the Yuan Dynasty. We have two examples. In the “Hun Yi Jiang Li Li Dai Guo Du Zi Tu” (Map of the Entire Empire and Frontier Countries) made by Quan Jin in 1402, based on maps from the Yuan Period, the Philippines is included in the lower part of the map. But, it appears as only as a collection of small vague patches, indicating only the largest islands of Mindoro and parts of Palawan. Huangyan Island is not indicated at all. (Figure 5)

Figure . The “Map of the Entire Empire and Frontier Countries” drawn in 1402 based on Yuan Dynasty maps. The Philippines appears as a small collection of spots in the lower right corner, west of the large patch that represents Japan. (Source: cartographic-images.net)

On the other hand, in the “Dong Han Hai Yi Tu” (Barbarian Countries of Southeast Seas) drawn by Lo Hsung-Hsien in the 15th century, again based on Yuan Dynasty maps, the Philippines appears as small blobs with markings for May-i (Mindoro) and Sansu (likely Calamian, Palawan, and Busuanga). Again, Huangyan Island is nowhere to be found.

Perusal of these maps of China based on information from the Yuan Dynasty period leads quickly to certain conclusions. One is that China of the Yuan period actually had very little information of the Philippines and its largest islands in terms of location, size, or shape. Chinese cartographers did not even give the Philippines much importance, as compared with Japan, Taiwan, and Hainan. Second, China at the time clearly did not have full and accurate knowledge of even the largest islands of our archipelago. If it could not even determine the location, size, or shape of Luzon, then much less could it identify the infinitesimal rocks and reef of Bajo de Masinloc. China could not possibly claim discovery in this period, since information from the period itself is non-committal.

Furthermore, Chinese records tend to indicate the reverse. According to them, as early as the 7th and 10th century, the ancestors of the Filipinos had established contact with China under the Tang Dynasty 700 years before the Yuan. Thus China knew very well that the islands of the Philippines were inhabited by coastal seafaring peoples. Chinese annals such as the “Chu Fan Chi” of Chau Ju Kuo even speak in fear of the slave-raiding expeditions of the Visayans, reaching as far north as the coast of Fujian Province. Thus, it was Philippine ancestors, not Chinese, who were the masters of the Southeast Asian seas.

Chinese records also speak of a lucrative trade in metals, weapons, musical instruments and jewellery reaching as far South as Butuan, one of the largest port polities of ancient times. These port polities were flourishing at a time when China withdrew into itself and abandoned trade with the outside world. It was the profitability of that trade that caused Chinese traders to lobby with their reclusive government to allow trade missions to and from Southeast Asia, and this eventually bore fruit.

So, if ever the Yuan Dynasty mariners came to the Philippines or any of its parts, it was because they knew that our ancestors were already there. These were not journeys of discovery of hidden places, but purposeful voyages to trade with known peoples and places.

As for the second basis of its claim, it bears noting that the name “Huangyan Island” was not on Chinese maps of the South China Sea until about 1983. The feature is reportedly indicated for the first time in the Chinese map of the South China Sea in 1935, and included as one of the features listed by the Water Mapping Committee in the original version of the now infamous 9 dashed lines map. The original map (containing 11 dashed lines), gave the reef the Sinicized name of Scarborough. Thus the very first name given for a place discovered in ancient times was the Chinese version of an English name given by English cartographers. This is stark evidence that as late as 1947, China did not even know of the shoal, and only became aware of it from British Admiralty charts.

In fact, Bajo de Masinloc does not receive any distinctly Chinese designation until it was renamed Minzhu Reef. The problem, however, is that it is listed as part of the Nansha Qundao, or the Spratly Islands. The Spratlys are a totally distinct group of islands some 260 nautical miles away from Bajo de Masinloc. It is difficult to conceive of a proper and effective naming of a place when its location does not even appear to be known. China did not call the place Huangyan Island until after 1983, nearly 40 years later, after it sent its first recorded hydrographic survey to the area without informing the Philippines. It is reasonable to surmise that the change in designation and grouping was a direct result of that modern survey; and that it was only in 1977 that China actually reached Bajo de Masinloc, and realized that it could be more than a reef.

The reason for its designation as an “island” is clear: it is the only feature above water in the imaginary Zhongshe Qundao that supposedly lies between the Paracels and the Philippines. As such, it is the only feature that can justify China’s claim to the existence of Zhongshe Qundao which includes the completely-submerged Macclesfield Bank.

If the location of what China now calls Huangyan Island was not even known and fixed until 1983, then it becomes eminently clear that the claim to continuous exercise of jurisdiction is unsubstantiated. For China, Huangyan Island only came into existence in 1983, and it was nothing more than a pinpoint on a map as far as its government was concerned. The only time it attempted to exercise any kind of jurisdiction over Bajo de Masinloc was in 1994, when it issued a permit to an amateur radio operator to set up an amateur radio station on the shoal, igniting the present day dispute over it.