‘Made In China 2025’: a peek at the robot revolution under way in the hub of the ‘world’s factory’

In the second report in a series, He Huifeng and Celia Chen look at how Beijing's ambitious industrial plan aims to break China’s reliance on foreign technology and pull its hi-tech industries up to Western levels

Amid the sprawl of drab, dusty concrete factories in Shunde district in the southern Chinese city of Foshan, one gleaming new structure stands out.

The 40,000 square metre (430,000 square feet) factory, designed by an American architect, cost 120 million yuan (US$17.5 million) to build and is expected to triple Jaten Robot & Automation’s annual production to 10,000 robots.

Just a few miles away, work is under way on an 800,000 square metre, 10 billion yuan industrial estate that will house three ventures between Chinese appliance maker Midea and German robotics firm Kuka, which Midea bought in 2016. The new complex will have the annual capacity to produce 75,000 industrial robots by 2024.

Jaten and Midea are among the biggest players helping to make Foshan – a city of 7 million people best known as the home of the Cantonese style of lion dance and kung fu – the hub of China’s robotics industry.

Under the Chinese government’s “Made in China 2025” industrial master plan, the number of industrial automatons operating in the country would expand tenfold to 1.8 million units by 2025, when up to 70 per cent of the robots used in China would be made in the country, from half in 2020, and 30 per cent now.

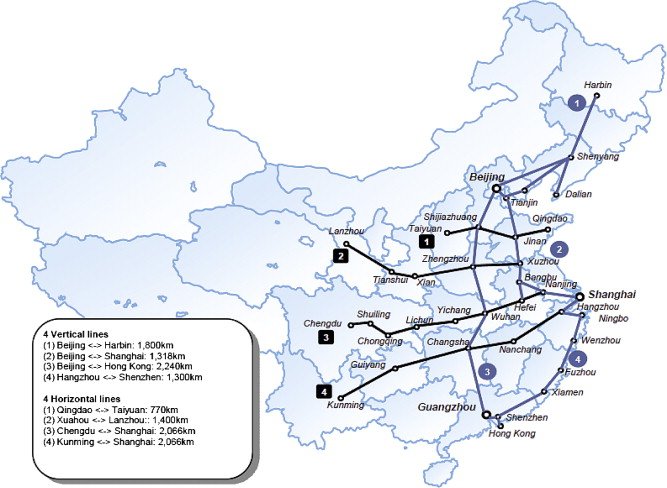

It’s an ambitious, multibillion-dollar pursuit. Sitting on the western bank of the Pearl River, with Guangzhou city to the north and Shenzhen to its east, Foshan is at the heart of southern China’s manufacturing industry.

Guangdong province is China’s largest regional economy, accounting for 10.4 per cent of the country’s 2016 gross domestic product, and 11.4 per cent of the industrial base, according to the statistics bureau.

“China is the factory of the world, and there are millions of manufacturers that still depend on traditional labour-intensive methods,” said Ren Yutong, executive president of the Guangdong Robotics Association, a government think tank. “If the country wants to maintain its top spot as a global exporter, each Chinese manufacturer has to start replacing humans with robots due to skyrocketing labour costs and the ageing population. [China] has already started running out of workers.”

The number of domestically made industrial robots sold in China rose 58 per cent last year to 141,000 units, according to government statistics.

Because of China’s outsize workforce, the density of automation usage lags other countries: 68 robots per 10,000 industrial workers, compared with 631 bots for every 10,000 manufacturing staff in South Korea, the global leader in automation. Singapore, Germany and Japan all have higher densities of automation than China.

China wants to more than double that usage density to 150 for every 10,000 workers by 2020. To do so would require massive amounts of government help.

The Guangdong provincial government offered 943 billion yuan in subsidies between 2015 and 2018 to help local manufacturers automate. Further up north in Zhejiang province, local authorities have set aside 800 billion yuan to spur 36,000 enterprises to make a similar switch by 2020.

SowoTech, a Dongguan-based producer of auto-cutting laminator robots integral to the production of printed circuit boards, was offered 3 million yuan last year from the municipal government, and another 1.5 million yuan from the hi-tech area where it is located, as subsidies on 80 million yuan of sales, according to a Chinanews.com report.

Other robot producers in the Songshan Lake Hi-tech Industrial Development Zone similarly would receive up to 1 million yuan in subsidies each to attend conventions and fairs on automation and robotics, the report said.

“The top-down [development] approach [in Made in China 2025] is helping, and the government is doing the right thing in promoting the protection of intellectual properties,” said Angus Muirhead, senior portfolio manager for Credit Suisse’s global robotics equity fund in Zurich.

The opening of the government tap is a bonanza for robotics makers. The 400 companies of the Guangdong industry guild could expect “double-digit” sales growth for their robots for the next few years, Ren said.

A skilled factory worker earns about 36,000 yuan a year in wages and benefits in China’s poorer provinces and second-tier cities, away from the coast. Total remuneration can exceed 60,000 yuan in cities nearer the coast and along the eastern seaboard, like in the Pearl River and Yangtze River deltas.

A 200,000 yuan robot that can do the job of three humans can recoup its capital cost in 22 months in central provinces, or in a little over a year in coastal cities. In the face of rising prices pressures for labour, energy and rents, such a cost advantage would be attractive to many manufacturers.

Jaten is one of the biggest makers of self-navigating robots used on assembly lines and warehouses. With

, each robot – which can navigate autonomously along a grid in any factory space or warehouse and can lift between 500 kilograms to 40 tonnes of load – costs between 100,000 yuan and 1 million yuan.

Company vice-president Chen Hongbo said that with the help of the generous subsidies and incentives, Jaten was aiming to increase its annual sales by 150 per cent, to surpass 1 billion yuan by 2021, when half of its production would be exports.

It would happen because of the “irreversible trend” of automation, and the “vast amount of subsidies” for upgrading, he said.