You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

News on China's scientific and technological development.

- Thread starter Quickie

- Start date

Hong Kong students triumph at 33rd International Olympiad in Informatics (with photo)

A team of four students representing Hong Kong achieved excellent results in the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) 2021, winning one gold medal and three silver medals. A total of 88 countries or regions from all over the world participated in this year's IOI, the 33rd event, which is the most recognised worldwide computer science competition aimed at secondary students under 20 years of age.

The four students awarded at the IOI 2021 () are as follows:

Gold Medal: Harris Leung (Diocesan Boys' School)

Silver Medal: Hsieh Chong-ho (Tsuen Wan Government Secondary School)

Xie Lingrui (La Salle College)

Yeung Man-tsung (Pui Ching Middle School)

The Secretary for Education, Mr Kevin Yeung, today (June 30) congratulated the team on their excellent performance. "It is very encouraging to see the remarkable achievements of the Hong Kong team in the IOI, the best record of Hong Kong since 1992. As one of the International Science Olympiads under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, the IOI aims at promoting coding education and nurturing students' computational thinking and problem-solving skills," he said.

"I also wish to extend my gratitude to the school sector for partnering with the Education Bureau (EDB) in the past few years to make great efforts to promote STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education in Hong Kong, not only through optimising the curriculum and classroom teaching, but also in providing various learning opportunities outside the classroom. For example, a team of aerospace scientists entered campuses last week to share with students the valuable experience of our nation's aerospace engineering, thereby inspiring students' enthusiasm for pursuing science and technology, exploring the unknown and taking the challenge to innovate. The EDB continues to support schools in promoting STEM education in schools. Through related learning activities, such as project work and competitions, we aim to develop a solid foundation in STEM-related areas among students and nurture their creativity, enable them to apply knowledge and skills to solve problems, enrich their learning experience and broaden their horizons."

Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the IOI 2021 was held in an online mode. The contestants participated within each participating country or region under online monitoring. They joined virtual activities from June 19 to 25, during which they were required to design and write a number of computer programs during the competition week. Contestants had to demonstrate good problem-solving skills and programming techniques in order to achieve desirable results.

Since 1997, the EDB and the Hong Kong Association for Computer Education have jointly organised the Hong Kong Olympiad in Informatics (HKOI), which aims to enhance the programming and problem-solving skills of students through the competition. Outstanding winners from HKOI are selected as Hong Kong representatives every year to enter the IOI. They are required to attend a series of training programmes to better prepare for the international competition. As a tradition of passing the torch, many of the trainers are previous contestants of the IOI.

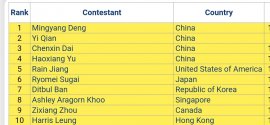

(The first 4 come from mainland China)

A team of four students representing Hong Kong achieved excellent results in the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) 2021, winning one gold medal and three silver medals. A total of 88 countries or regions from all over the world participated in this year's IOI, the 33rd event, which is the most recognised worldwide computer science competition aimed at secondary students under 20 years of age.

The four students awarded at the IOI 2021 () are as follows:

Gold Medal: Harris Leung (Diocesan Boys' School)

Silver Medal: Hsieh Chong-ho (Tsuen Wan Government Secondary School)

Xie Lingrui (La Salle College)

Yeung Man-tsung (Pui Ching Middle School)

The Secretary for Education, Mr Kevin Yeung, today (June 30) congratulated the team on their excellent performance. "It is very encouraging to see the remarkable achievements of the Hong Kong team in the IOI, the best record of Hong Kong since 1992. As one of the International Science Olympiads under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, the IOI aims at promoting coding education and nurturing students' computational thinking and problem-solving skills," he said.

"I also wish to extend my gratitude to the school sector for partnering with the Education Bureau (EDB) in the past few years to make great efforts to promote STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education in Hong Kong, not only through optimising the curriculum and classroom teaching, but also in providing various learning opportunities outside the classroom. For example, a team of aerospace scientists entered campuses last week to share with students the valuable experience of our nation's aerospace engineering, thereby inspiring students' enthusiasm for pursuing science and technology, exploring the unknown and taking the challenge to innovate. The EDB continues to support schools in promoting STEM education in schools. Through related learning activities, such as project work and competitions, we aim to develop a solid foundation in STEM-related areas among students and nurture their creativity, enable them to apply knowledge and skills to solve problems, enrich their learning experience and broaden their horizons."

Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the IOI 2021 was held in an online mode. The contestants participated within each participating country or region under online monitoring. They joined virtual activities from June 19 to 25, during which they were required to design and write a number of computer programs during the competition week. Contestants had to demonstrate good problem-solving skills and programming techniques in order to achieve desirable results.

Since 1997, the EDB and the Hong Kong Association for Computer Education have jointly organised the Hong Kong Olympiad in Informatics (HKOI), which aims to enhance the programming and problem-solving skills of students through the competition. Outstanding winners from HKOI are selected as Hong Kong representatives every year to enter the IOI. They are required to attend a series of training programmes to better prepare for the international competition. As a tradition of passing the torch, many of the trainers are previous contestants of the IOI.

(The first 4 come from mainland China)

Hong Kong students triumph at 33rd International Olympiad in Informatics (with photo)

A team of four students representing Hong Kong achieved excellent results in the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) 2021, winning one gold medal and three silver medals. A total of 88 countries or regions from all over the world participated in this year's IOI, the 33rd event, which is the most recognised worldwide computer science competition aimed at secondary students under 20 years of age.

Of the top 10, 8 are ethnic Chinese, and the other 2 are Japanese and Korean. I.e. 100% East Asian ethnicity.

This is another fine illustration that if US truly wants to decouple, it would end up losing many of their best people in STEM. They would be hard pressed to execute decoupling without creating an anti-Asian atmosphere. After all, it is not easy to tell a Chinese from a Japanese or Korean.

Congrats China for having the only all gold team.View attachment 74097

Of the top 10, 8 are ethnic Chinese, and the other 2 are Japanese and Korean. I.e. 100% East Asian ethnicity.

This is another fine illustration that if US truly wants to decouple, it would end up losing many of their best people in STEM. They would be hard pressed to execute decoupling without creating an anti-Asian atmosphere. After all, it is not easy to tell a Chinese from a Japanese or Korean.

broadsword

Brigadier

All the reps from USA were also ethnic Chinese.

Chinese breakthrough allows physicists to build the world’s most powerful laser

A research team in Shanghai has achieved a technological breakthrough to allow them to build the most powerful laser on the planet.

The leap means they could fire a 100-petawatt shot in about two years, a scientist involved in the project told the South China Morning Post on Tuesday.

That single pulse would be 10,000 times more powerful than all the electricity grids in the world combined.

In the incredibly brief but intensive flash of light, humans would witness materials coming from nothing for the first time.

Liu Jun, a member of the Station of Extreme Light (SEL) project with the Shanghai Institute of Optics and Fine Mechanics, said increasing the power of a laser beam was not easy.

A very high energy input could damage optical components such as crystals, lenses and mirrors.

To sidestep the burn issue, scientists would diffract the input beam to a broad spectrum of colours and pump into each colourful beam a relatively small amount of energy that the hardware could tolerate. Then they would compress them back into a single beam, now with its power dramatically amplified.

This compression has been an obstacle for scientists around the world for decades.

"The compressor will burn with so much energy coming in," Liu said.

In a 19-page paper published in the journal Optics Express in May, Liu and his colleagues proposed a high-powered laser design that broke the compression procedure into steps, which they said would cut energy intensity to a level safe for the compressor while radically increasing the laser device power output.

This breakthrough has given the SEL facility, which is under construction in Shanghai, a boost, according to Liu.

The $100 million project originally planned to employ four independent laser beams to reach the target power output. But with the new technology, one beam would be enough.

This would reduce the number of some large, critical components, such as diffraction gratings, and cut the cost of the project, said Liu.

"The fewer the beams, the simpler the device. The simpler the device, the more easily it can be built and run. The quality and stability of laser pulses will improve as well," he added.

When completed in 2023, the SEL facility could open a portal to a new world of physical discoveries, many physicists believe.

Though the laser beam eventually would be fired up in extremely short pulses ― with no risk of a blackout on Earth ― experts believe it would tear apart space-time for a brief moment to allow scientists to glimpse new physical phenomena that for now only exist in theories.

Einstein's famous equation E=mc2, for instance, explains that a small amount of matter can be converted to an enormous amount of energy. The atomic bomb proved it. But no one has shown how ― or whether ― it works the other way round.

The extremely powerful laser beam, when focused on an extremely small spot in a vacuum, can make a subatomic particle pop out of the blue, according to the prediction of physical theory. The SEL was designed to make this happen.

But the use of the facility will not be limited to satisfying physicists' curiosity. It could aid research in a wide range of areas, from new materials and drugs to nuclear fusion energy.

A laser scientist with the Institute of Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, said the new Shanghai laser facility would strengthen China's leading position in the high-power laser race.

Some research teams in Russia, Europe and the United States have proposed similar projects, but none has received sufficient funding from their government, said the physicist who was not involved in the project and requested not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

"China will almost certainly win," he said.

The current laser record is 10 petawatts using several beams. Producing a single laser beam 10 times as powerful is an ambitious goal. The design by the Shanghai team was like no others, the unnamed physicist said.

So there would be more challenges ahead, he said, adding that similar large-scale research infrastructure projects built in China had a good record for meeting deadlines, nonetheless. He said many physicists in the world were tracking the Shanghai project.

"Even competitors wish for their success," he said.

Shuai Ke, a top scholar in the field of international life sciences, resigned from the US teaching position and joined Nanjing University

Chinese scientists realize the fastest real-time quantum random number generator to date

Chinese scientists make remarkable achievement in long-haul fiber quantum network

deleted

Last edited: