You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Miscellaneous News

- Thread starter bd popeye

- Start date

Here is a link with details, there are quite a few graphs by country.

I wrote before in this thread that anti-China rhetoric is not popular in my home country Bulgaria and this study confirms that fact. Unfortunately in Sweden, where I live, Russophobia and Sinophobia are at the other pole.

In April 2023, ECFR conducted an opinion poll across 11 EU member states – Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden – to understand how European citizens see their place in the world today. The results of the poll show that their cooperative foreign policy instincts are adapting slowly to the new geopolitical reality that is characterised by growing polarisation.

Germany, Sweden, France, and Denmark are the only countries where the prevailing view is to see China as a “rival” or an “adversary”, rather than an “ally” or “partner”. Paradoxically, von der Leyen’s call to de-risk Europe’s relations with China finds sympathetic audiences in the two countries – France and Germany – whose leaders have, so far, promoted a considerably more obliging approach.

The prevailing view in almost every country included in our survey is that the risks and benefits of Europe’s trade and investment relationship with China are balanced; Bulgarians even consider the benefits to outweigh the risks. In no country did most respondents consider Europe’s trade with China to entail more risks than benefits.

However, if Beijing decided to deliver ammunition and weapons to Russia, many Europeans would consider this a red line. On average, 41 per cent would be ready to sanction Beijing in that event, even if that meant seriously damaging Western economies. A minority of 33 per cent, on average, would oppose this.

Still, European countries are far from united on this. According to the results of our survey, only in Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands would an absolute majority be in favour of such sanctions. Meanwhile, in Austria, Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria, there is a clear preference against such a move – constituting a major constraint on governments. Some practical reasons may explain this. The Swedish and Danish economies rely much less on trade with China than those of Italy and Germany, making sanctions less costly for the former. At the same time, Italian and Bulgarian households are more economically vulnerable than those of northern Europe.

Moreover, Europeans display considerable caution about the practical aspects of China’s economic presence in Europe, for example, whether Chinese companies should be allowed to build and own infrastructure in Europe or buy newspapers, technology companies, and football clubs. On average, a majority would oppose allowing Chinese companies to own infrastructure in Europe, as well as to buy a European newspaper or technology company. We asked the same question in late 2020 and, since then, Europeans have grown somewhat more concerned about China’s economic presence in Europe – especially in Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Hungary. Currently, the three countries in which the population is most opposed to China’s economic presence are Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands – while Bulgaria and Spain are the most open to it.

United on Russia

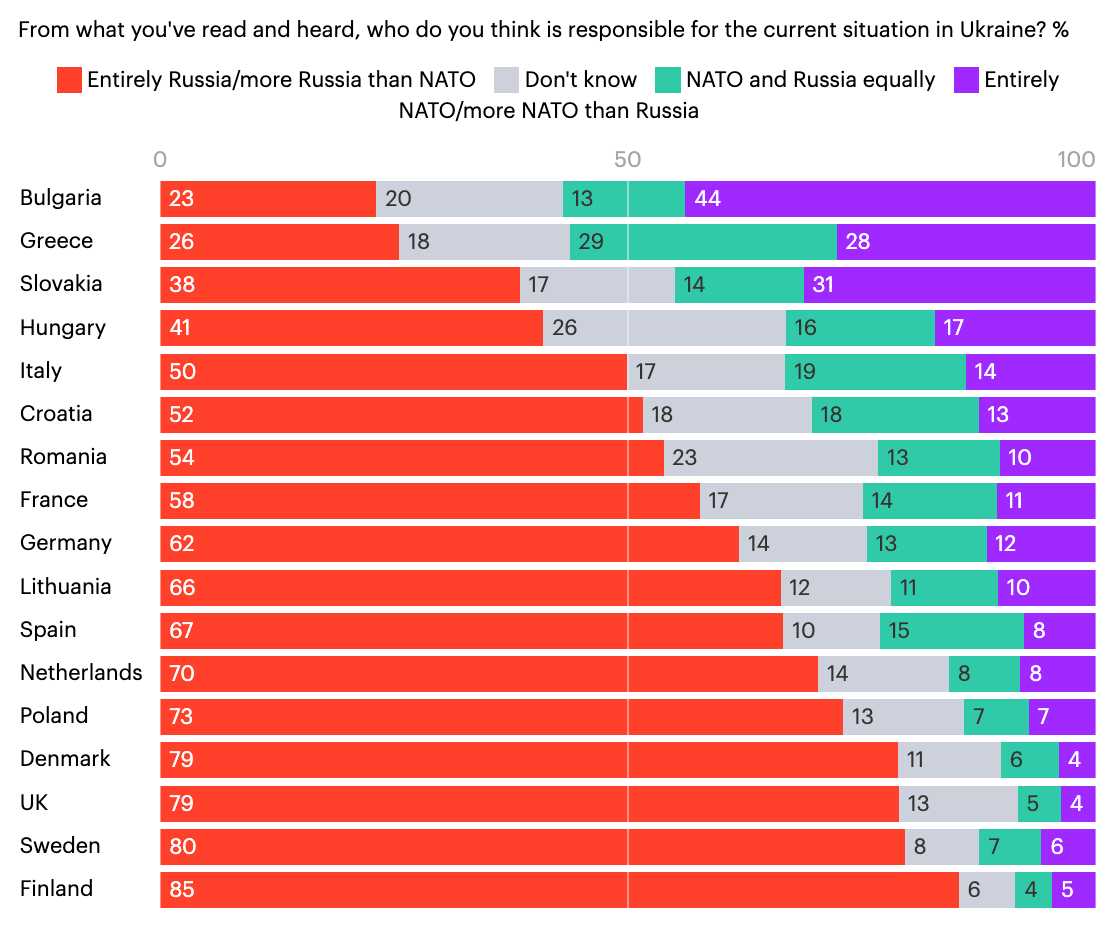

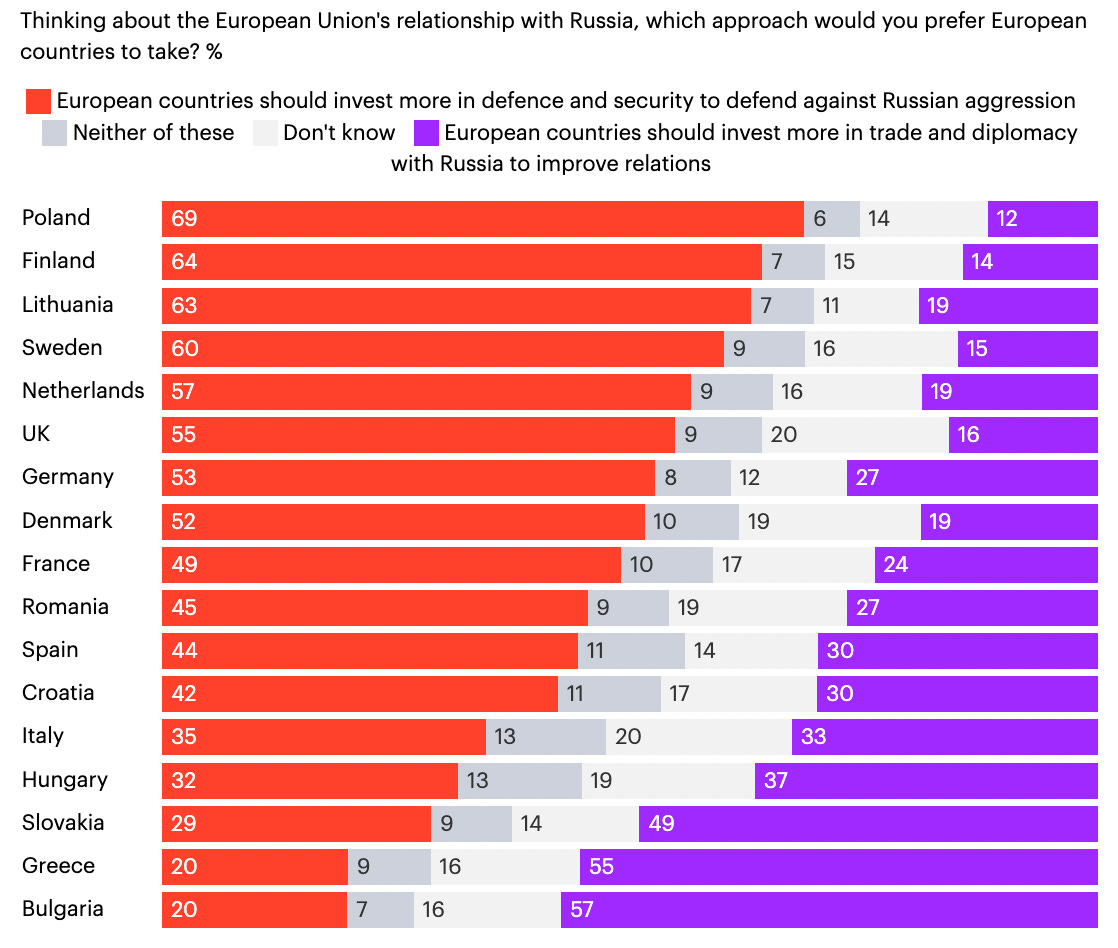

In contrast, Europe’s relationship with Russia has undergone a real Zeitenwende. With the exception of the Hungarian leadership, European governments have been strongly united in their support for Ukraine and their opposition to Russia. In most surveyed countries, a majority agrees that Russia is their country’s – and Europe’s – “adversary”. Out of the countries included in our survey, the populations of Poland, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany are the main hawks in this respect.

In most cases, the public’s views on Russia have changed significantly since our 2021 survey. On average, the share of respondents who see Russia as Europe’s “rival” or “adversary” has increased from around one-third to almost two-thirds; at the same time, sympathies towards Russia have dropped considerably. Among the surveyed countries, Bulgaria is the only one where the majority of the public continues to see Russia as Europe’s “ally” or “partner”, and where little has changed in that respect since 2021. (When asked about “their country’s” relationship with Russia, the majority in Hungary, as well as in Bulgaria, sees Russia as an “ally” or “partner”.) There is currently a clear mandate in Europe for a policy that seeks to establish European security not with Russia but against it.

In every country that we surveyed, 50 per cent or more would like their countries to re-establish at least some form of relations with Russia if the war ends in a negotiated peace. In Poland, 39 per cent are willing to end all relations with Russia. Meanwhile, a majority in Bulgaria are already considering re-establishing a fully cooperative relationship with Russia after the war. It would be dangerous if European discussions on this issue were driven by these extreme positions.

It's not going to work in the US... For obvious weight reasons... That smiling lady is just lolJust imagine an emergency evacuation from this plane.

I don't know unless the seats are not porous, Imagine sitting under a dude farting the entire time

Also, no reclining. So its gonna be quite uncomfortable.The concept probably not doable from a safetly perspective since the bottom people could easily hit their heads in sudden turbulance, crashes , braking.

Also if yall have seen those aircraft evacuation tests, passengers often climb above the seats to reach the emergency exit. This is not possible in this design and would cause people to funnel into the center aisle and cause congestion during an emergency (like a fire) which is no bueno.

Another issue is during a crash, lmao that poor lady sitting below is gonna have her head smashed into the metal lmao.

Last edited:

Engineer

Major

Cattle class is expendable. There will be no need for evacuation.Just imagine an emergency evacuation from this plane.

Here is a link with details, there are quite a few graphs by country.

I wrote before in this thread that anti-China rhetoric is not popular in my home country Bulgaria and this study confirms that fact. Unfortunately in Sweden, where I live, Russophobia and Sinophobia are at the other pole.

Some notable exclusions: Norway, Finland, Czech Rep, which are presumingly quite pro-US and anti-China to varying degree, what about Croatia and your neighbor Romania? Croatia and Greece are fairly for pro-Russia correct?

Oh god, if someone at the top farts... down it goes straight to the face of the person belowJust imagine an emergency evacuation from this plane.

manqiangrexue

Brigadier

I don't think so. Democracy is rule by the will of the people. It has only become an ugly word due to how the West has mangled it and then presented the mangled version of it to the world as democracy. China is truly a land where the government is extremely sensitive to the people's will and any corruption that is revealed, immediately and harshly dealt with to abate any feelings of unfairness in the people. This is closer to real democracy than anything in the West. The West says that it's democratic but the only thing democratic about it is the use of elections, which are represent a very thin veneer of real democracy. The fact is that the people are forced to choose candidates based on who they hate less, then when they get into office, they are lobbied into doing things nobody wants and protests don't do anything. No matter who you elect, your taxes are going up and police are taking over your city with Draconian laws; the people are only allowed to quibble on the details of how that process is to take place with no power to stop them from happening. In Germany, it's a crime to express an opinion against Ukraine for Russia. Same in the UK with the monarchy. In some places, the politicians openly say that no matter what the citizens want, no matter how hard the people protest and fight, they will put Ukraine first without regard to public will. And even this totally bullshit version of democracy is an overly kind summarization for some countries because CIA hacking can simply give the outcome of elections to the candidate most willing to sacrifice that country to support American interests against their own people. This is why we hate "democracy." The West has tricked people into thinking that this is democracy. In China, there are no direct elections, but the will of the people is carried out by more complex, sensitive and advanced mechanisms. If there is an online trend, the government follows and adjusts to it. If there is a protest, the government tries to solve the problem in the area. If corruption or incompetence is reported and made public, the official is sacked. In the US, it's perfectly legal for politicians to be corrupt and fail at everything they do and even if they step over the line and get caught, they continue to serve for years and years until their lengthy court case is washed away with time and they get off scott free. If anything, China's success is because China is more democratic than the West by far, to the true definition of the word, not the Western bastardization of it.

I thought that this was definitely the Onion until I read that it definitely wasn't.

Yep, Bulgaria, Greece, Slovakia, Hungary. But public opinion is irrelevant, specifically for my home country Bulgaria. The country is run by the American embassy in Sofia. We all know that, it's not even a secret.Some notable exclusions: Norway, Finland, Czech Rep, which are presumingly quite pro-US and anti-China to varying degree, what about Croatia and your neighbor Romania? Croatia and Greece are fairly for pro-Russia correct?

This study is from June last year:

This Swedish synophobe Jojje Olsson is very disappointed:

Last edited: