You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

ISIS/ISIL conflict in Syria/Iraq (No OpEd, No Politics)

- Thread starter Jeff Head

- Start date

Jura The idiot

General

well, I got your sarcasm inI do hope your not being deliberately obtuse there Jura.

https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-451#post-419728

but didn't get your sarcasm in

https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-452#post-419878

as Russians target both insurgents (presumably in the video you posted) and civilians (presumably in the video in my rebuttal https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-453#post-420091), as you indicated below:

so, since I didn't get your sarcasm, I reacted on the assumption you had lauded how Russian intervention in Syria is sold in outlets like Sputnik (an example of what I mean: https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-412#post-411225)As you are very well aware, the accusation against Russia and Syrian Air Forces is that they are deliberately targeting civilian targets. The video I posted shows very clearly that whatever else the targets being hit are, they are most definitely not civilian!

War is a nasty and dirty business and if terrorists fortify themselves and their Arsenals in civilian areas and infrastructure, they do so knowing that they are deliberately putting those civilians in harms way, as their enemies will have no option but to attack those targets.

What is true in Aleppo well even more true in Mosul, so maybe the Western propaganda will itself be good enough to stop?

now I see I probably misunderstood your position, and I'm sorry

actually a Russian blogger

reposted a video which purports to show a hospital in Mosul bombed today

EDIT

sometimes Western Propaganda works in a strange way even from a technical viewpoint, for example last(?) month I happened to see in the news of a major TV station here, in prime time, a report how Western Coalition bombs ISIL and how it's going well; during that time they were showing Tu-22Ms in action

Last edited:

Jura The idiot

General

Sunday at 10:37 AM

(as for scale ... it would be something like ten miles to Al-Bab, so just about three (?) to Government positions)

(as for scale ... it would be something like ten miles to Al-Bab, so just about three (?) to Government positions)

... and only after I had read it in Twitter I realized soon Rebels/Turks should "border" with Government to the nort-east from Aleppo:Yesterday at 9:49 PM

seconds ago I read in Twitter they're in both Sawran and (picture below) Dabiq:

...

Jura The idiot

General

Yesterday at 8:40 PM

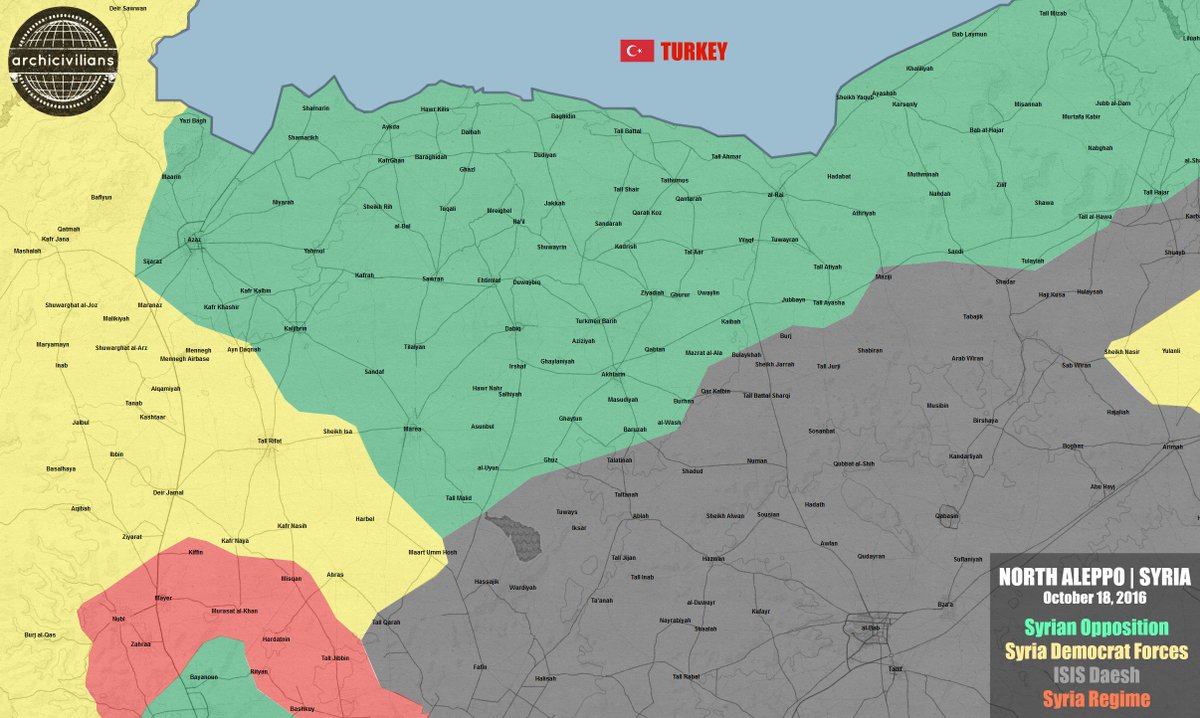

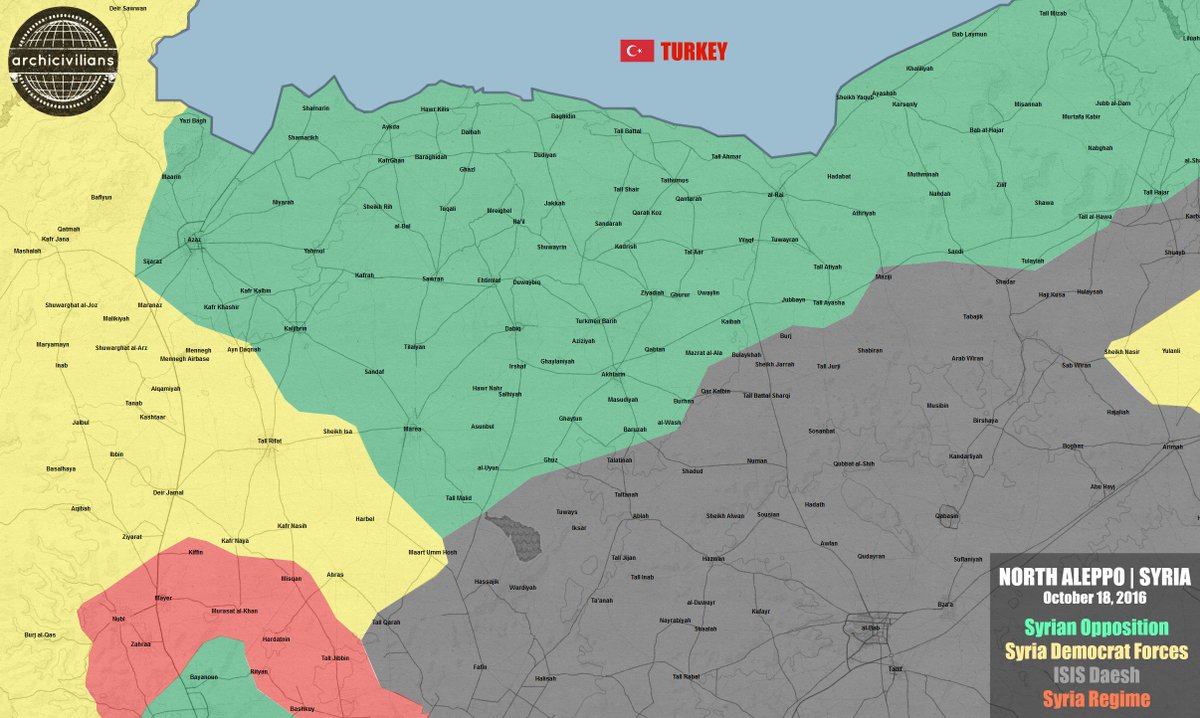

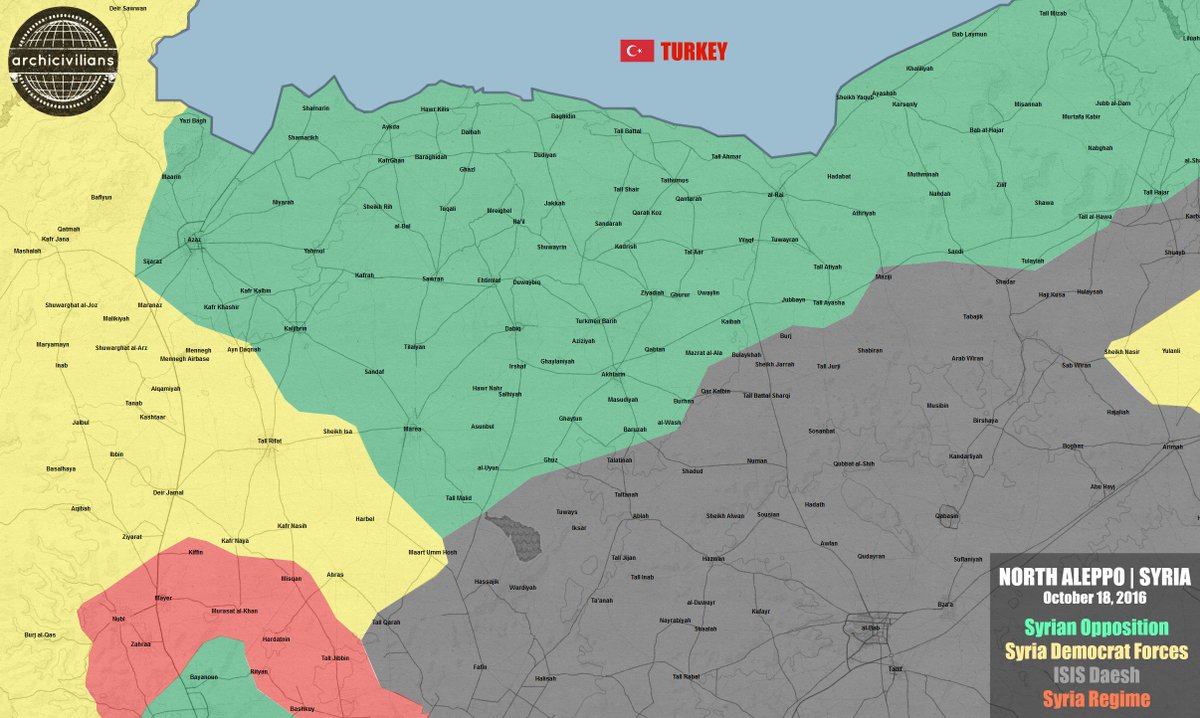

related is the fresh recent "edmap":... and only after I had read it in Twitter I realized soon Rebels/Turks should "border" with Government to the nort-east from Aleppo:

(as for scale ... it would be something like ten miles to Al-Bab, so just about three (?) to Government positions)

Jura The idiot

General

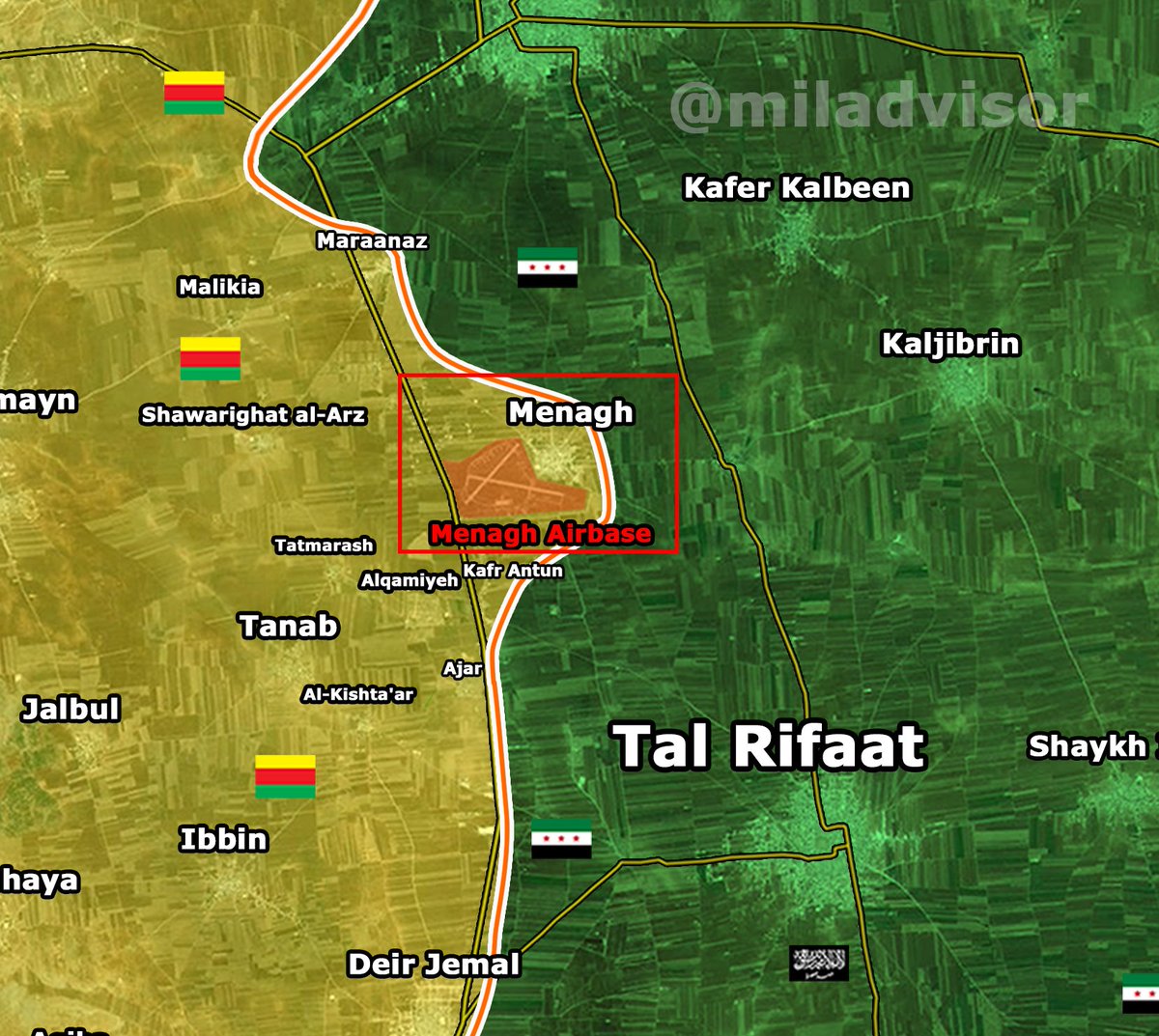

I'll make it a separate post (it concerns the area in the middle-left part of the map right above):

I read in several Twitter accounts (could be just sabre rattling) Rebels/Turks wanted "Tall Rif'at" back from Kurds now, so I looked up:

Feb 10, 2016

(I couldn't find here when exactly Kurds won Tal Rifaat because of ...

https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-341#post-388905 and what followed)

EDIT

now I see "Tell Rifaat was captured by the on 16 February 2016"

I read in several Twitter accounts (could be just sabre rattling) Rebels/Turks wanted "Tall Rif'at" back from Kurds now, so I looked up:

Feb 10, 2016

(to the northwest from Aleppo):

OK three sources now:

has been captured by

(I also saw Rebels' denial though)

(I couldn't find here when exactly Kurds won Tal Rifaat because of ...

https://www.sinodefenceforum.com/is...o-oped-no-politics.t6913/page-341#post-388905 and what followed)

EDIT

now I see "Tell Rifaat was captured by the on 16 February 2016"

Last edited:

Jura The idiot

General

now I read (published when I slept hehe October 17 at 6:37 PM) Russian air defense raises stakes of U.S. confrontation in Syria

inside is this graphics:

source:Russia’s completion this month of an integrated air defense system in Syria has made an Obama administration decision to strike Syrian government installations from the air even less likely than it has been for years, and has created a substantial obstacle to the Syrian safe zones both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have advocated.

Deployment of mobile and interchangeable S-400 and S-300 missile batteries, along with other short-range systems, now gives Russia the ability to shoot down planes and cruise missiles over at least 250 miles in all directions from western Syria, covering virtually all of that country as well as significant portions of Turkey, Israel, Jordan and the eastern Mediterranean.

By placing the missiles as a threat “against military action” by other countries in Syria, Russia has raised “the stakes of confrontation,” Secretary of State John F. Kerry said Sunday.

While there is some disagreement among military experts as to the capability of the Russian systems, particularly the newly deployed S-300, “the reality is, we’re very concerned anytime those are emplaced,” a U.S. Defense official said. Neither its touted ability to counter U.S. stealth technology, or to target low-flying aircraft, has ever been tested by the United States.

“It’s not like we’ve had any shoot at an F-35,” the official said of the next-generation U.S. fighter jet. “We’re not sure if any of our aircraft can defeat the S-300.”

For more than two years, Syria has tacitly accepted U.S. and coalition airstrikes against the Islamic State, in areas relatively far afield from where the civil war is being fought. An agreement signed by Moscow and Washington last fall, after Russia sent its own air force to join that of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, is designed to ensure that U.S. and Russian planes stay well away from each other.

But the ongoing Russian-Syrian siege of Aleppo, and the failure of diplomatic negotiations to stop it, has forced the administration to reconsider its options, including the use of American air power to ground Assad’s air force.

The possibility of using U.S. air power in the civil war, even to patrol a safe zone for civilians, has never been favored by the Pentagon, which has argued that it would involve preemptory strikes on Syria’s fixed air defenses. Now, with the installation of a comprehensive, potent Russian air defense system, many military officials see it as risking a great power game of chicken, and possible war, according to senior administration officials.

Several officials spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss Russian capabilities and recent high-level White House meetings on Syria, Iraq and the Islamic State, including a Friday gathering of the National Security Council chaired by President Obama. The NSC session largely focused on the Mosul offensive begun against the Islamic State this week, and an upcoming operation against the militants in the city of Raqqa, their Syrian headquarters.

Consideration of other alternatives, including the shipment of arms to U.S.-allied Kurdish forces in Syria, and an increase in the quantity and quality of weapons supplied to opposition fighters in Aleppo and elsewhere, were deferred until later, officials said. U.S. military action to stop Syrian and Russian bombing of civilians was even further down the list of possibilities.

Another senior official dismissed what he called Moscow’s “yard sale approach” of displaying all available systems to attract potential purchasers, and said last month’s S-300 deployment did not much change Russian capabilities from where they have been over the past year. Russian arms sellers have repeatedly hailed the performance of their weaponry in Syria and claimed heightened sales abroad.

U.S. strikes in heavily populated western Syria, despite the presence there of al-Qaeda-affiliated forces of the Front for the Conquest of Syria, formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra, have been few and far between, precisely to avoid the risk of civil war involvement and, more recently, confrontation with Russia.

An attack early this month that eliminated a senior Front official in Idlib province, in northwestern Syria, was carried out by an unmanned U.S. drone, with notice provided to Russia.

Moscow has denied that Russian and Syrian attacks have intentionally struck civilians, saying they are directed toward the Front, some of whose forces are mixed with the rebels in Aleppo and elsewhere. In early September, Kerry said the United States would join with Russia in attacking the al-Qaeda forces, in exchange for a Russian and Syrian cease-fire and the delivery of humanitarian aid to besieged civilians.

It was when that agreement fell apart — and the United States suspended contacts with Russia over Syria as hundreds of civilians have been killed in the brutal bombing of Aleppo — that the Russians moved to install S-300 missiles. They formed the final component of an integrated air defense system, along with S-400 and other surface-to-air systems previously deployed in and around Russia’s Hmeimen air base in Latakia province along the Syrian coast.

Amid widespread talk of U.S. “kinetic” action to stop the Aleppo slaughter, the Russian Defense Ministry warned of the “possible consequences,” noting that “the range [of the defense systems] may come as a surprise to any unidentified flying objects.”

Russian soldiers and officers, it said, were working on the ground throughout territory controlled by the Syrian government and “any missile or airstrikes . . . will create a clear threat to Russian servicemen.”

In addition, the ministry said, following the Sept. 17 U.S. airstrike that inadvertently killed dozens of Syrian soldiers in eastern Syria, “we have taken all necessary measures to avoid any such ‘mistakes’ against Russian troops and military installations in Syria.”

Neither the administration, nor either of the presidential nominees, has ever favored using U.S. combat forces in Syria’s civil war. But the use of air power to create a zone inside the country where civilians could be safe from relentless airstrikes by Syria and Russia has long been advocated by regional allies and domestic critics of what is seen as a weak administration policy.

Both Clinton and Trump have favored such a strategy — in Clinton’s case, since she was secretary of state. Trump has advocated establishing a safe zone inside Syria as a way to stem the flow of Syrian refugees to Europe and this country.

But while such zones — protected by U.S. air power — were established during years past in Iraq, Libya and Bosnia, all were against relatively weak opponents and conducted under United Nations authorization. Neither presidential nominee has addressed the question of comprehensive Russian air defenses.

Although Kerry has continued to try to revive the cease-fire, U.S. leverage against Russia appears minimal. Following talks with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and U.S. European and regional allies last weekend, Kerry said that increased sanctions against both Russia and Syria were under consideration.

Meanwhile, Russia on Monday offered an eight-hour pause to the Aleppo bombing this week to allow Front militants and civilians to leave the city.

inside is this graphics:

BBC are reporting the "first large group of civilians" to escape from Mosul

Two issues spring to mind:

One it is a drop in the Ocean and at that rate would take years to make any substantial population reduction.

Two, if ISIS is going to make civilian human shields a central plank of their strategy and prevent people from leaving, it makes it more likely that the ones that do get out are simply the families of ISIS fighters.

Two issues spring to mind:

One it is a drop in the Ocean and at that rate would take years to make any substantial population reduction.

Two, if ISIS is going to make civilian human shields a central plank of their strategy and prevent people from leaving, it makes it more likely that the ones that do get out are simply the families of ISIS fighters.

Realy arguable Syrian have again Bastion coastal unit operationnalnow I read (published when I slept hehe October 17 at 6:37 PM) Russian air defense raises stakes of U.S. confrontation in Syria

source:

inside is this graphics:

In 2010 Sergei Prikhodko, senior adviser to the Russian President, has said that Russia intends to deliver P-800 to based on the contracts signed in 2007. Syria received 2 Bastion missile systems with 36 missiles each (72 in total). The missiles' test was broadcast by Syrian state TV.

In May 2013, Russia continued the contract delivery to the Syrian government supplying missiles with an advanced radar to make them more effective to counter any future foreign military invasion. The warehouse containing the Bastion Missile was destroyed in an Israeli air strike on on 5 July 2013, but US intelligence analysts believe that some missiles had been removed before the attack.

Some say also a part to Hezbollah...

plawolf

Lieutenant General

BBC are reporting the "first large group of civilians" to escape from Mosul

Two issues spring to mind:

One it is a drop in the Ocean and at that rate would take years to make any substantial population reduction.

Two, if ISIS is going to make civilian human shields a central plank of their strategy and prevent people from leaving, it makes it more likely that the ones that do get out are simply the families of ISIS fighters.

I think ISIS are keeping the civilians trapped more than just as human shields. Those civilians will also be their exit strategy.

Hell, they may even use them as offensive weapons like the Mongels did back in the day.

A favourite tactic the Mongols used to employ was to herd captives and local civilians ahead of their advancing armies when attacking enemy fixed positions.

They would release the civilians, and then start slaughtering those at the back, driving the desperate mass forwards as everyone rushes to escape the blades of the Mongols.

The fleeing civilians shields the

mongol soldiers from attack, and often fill trenches with their bodies and break through barricades and fortifications in their desperation.

The defenders end up facing the impossible choice of allowing their defences to be bogged down or even breached by the civilians, or kill them, which often destroyed the moral of their troops when ordered to do so.

I fully expect ISIS to use similar tactics once Iraqi and coalition forces enter Mosul.

Just picture waves of terrified and desperate civilians fleeing towards Iraqi lines and positions with ISIS suicide troops driving them with rounds into the back of the crowd, and maybe suicide bombers mixed in with the crowd itself.

The Iraqis will either have to shoot the civilians to get at the ISIS troops, or risk getting completely overrun.

Same deal if ISIS wants to mount a break out.

It will be near impossible to set up screening in such circumstances. Once the civilians break the cordon and scatter, it will be very hard to round them up and weed out any ISIS fighters.

Unless the Iraqis and coalition considered these dark ages tactics and made peace with the awful choices they might be forced to make, there is a very high chance this attack will flounder if ISIS use these or even worse moral traps on unprepared Iraqi and coalition forces.

now I read (published when I slept hehe October 17 at 6:37 PM) Russian air defense raises stakes of U.S. confrontation in Syria

source:

inside is this graphics:

Russian air defenses and reinforcements are primarily to ensure Turkey and its sponsored rebels in the north not make a move against Syrian government forces. Though it discourages US, and Israeli, aircraft from attacking as well.

Per your observation:

Sunday at 10:37 AM

... and only after I had read it in Twitter I realized soon Rebels/Turks should "border" with Government to the nort-east from Aleppo

...