You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chinese Economics Thread

- Thread starter Norfolk

- Start date

Jura The idiot

General

now I read

China details opening-up measures in financial sector

Updated 2018-04-11 12:48 GMT+8

China details opening-up measures in financial sector

Updated 2018-04-11 12:48 GMT+8

China's newly appointed central bank governor Yi Gang has announced a slew of reform measures regarding the foreign capital entering China’s financial market at the annual meeting of Boao Forum for Asia. This comes a day after , vowing a more open Chinese financial market.

The newly announced measures include canceling foreign capital’s holding ceiling in establishing commercial banks and financial asset management companies, allowing foreign banks to set up branches in China; raising ceiling of foreign holdings in stock brokerages, fund, futures companies, and life insurance companies to 51%, and the limit will be lifted three years later; quadrupling current quota of mainland Hong Kong stock connect from May 1; allowing qualified foreign investors to launch insurance agent and assessment business; allowing foreign insurance brokers the same business scope as their Chinese peers. Majority of these measures are expected to be implemented before the end of June this year.

The governor also says the central bank is also working on other opening up measures in the financial sector, such as allowing foreign capital to enter more banking businesses, like financial leasing and trust, and lifting a two-year representative office requirement for foreign insurance companies before they could set up a company. Moreover, with the presence of deputy chief at China’s securities regulator Fang Xinghai, Yi says China will try its best to launch the Shanghai London stock connect within 2018.

The official notices these measures are expected to boost Chinese financial companies' competitive ability in the global market.

Regulation in the financial market

When announcing the reform measures, the central bank governor also vows regulation in the financial sector will be stepped up in accordance with the opening up measures, to prevent financial risk and maintain market stability.

He also shares his thoughts on future regulation in the market. Current separate regulation works well, but may face difficulties when dealing with cross market activities. Yi mentions the central bank is currently working on guidelines in overall asset management market regulation, so as to make all asset management products to compete under the same rules, despite these products may come from different industries.

China US trade dispute

China’s monetary policy mainly focuses on domestic macro economy and serves the real economy, says Mr. Yi, when addressing a question on whether China will use monetary policy as a leverage in negotiating with US on trade dispute. He further explains that current market-based foreign exchange rate mechanism works fine, and will continue to work in the future.

He also shares his opinion on unnoticed factors behind the conflict. Though China has a trade surplus with US in terms of goods, it balances out as China also has a trade deficit with US in the field of service. And as China further opens up its services sector, American companies will have more advantages in the future.

Jura The idiot

General

now I read

Beijing launches point-based hukou system

Xinhua| 2018-04-11 17:00:58

Beijing launches point-based hukou system

Xinhua| 2018-04-11 17:00:58

Non-Beijingers will be able to apply for registration as permanent urban residents of China's national capital under the city's new point-based household registration system to open on Monday.

The much-coveted Beijing urban status is a crucial document entitling residents to social welfare. Many Chinese living outside Beijing are eager to apply for Beijing hukou, or household registration status.

Under the new policy, non-natives of the city under the legal retirement age who have held a Beijing temporary residence permit with the city's social insurance records for seven consecutive years and are without a criminal record are eligible to accumulate points for the hukou.

Those with good employment, stable homes in Beijing, strong educational background, and achievements in innovation and establishing start-ups in Beijing are likely to obtain high scores in the point-based competition for the city's hukou.

By the end of 2017, the number of people holding Beijing hukou reached 13.59 million, while the city's permanent population totaled 21.7 million in the same period.

The municipal government said the point-based household registration system will be open for applications between April 16 and June 14. After the time limit, the system will be closed, and applicants' files will be audited.

The city government said on Wednesday that it will announce this year's quota for new hukou holders after September 5. The quota is to be decided based on the city's population capacity. The winners' names, occupations and scores will be announced for public supervision in the fourth quarter.

Point-based hukou registration has been piloted in a number of big Chinese cities such as Shanghai and Xi'an, which are hot destinations for job-seekers. The system has proved to be fair and effective in satisfying the demand for personnel flow while limiting rapid growth in the permanent population.

Jura The idiot

General

now noticed the tweet

Les mines d'uranium de Hushan (湖山) en Namibie, qui détiennent la 3ème plus grosse réserve au monde, vont atteindre sa capacité de production maximale cette année avec 6 500 tonnes de brut par an. C'est le plus grand projet d'investissement chinois en Afrique.

Translated from French by

The Hushan uranium Mines (湖山) in Namibia, which hold the world's third largest reserve, will reach its maximum production capacity this year with 6 500 tonnes of crude per year. This is the largest Chinese investment project in Africa.

Les mines d'uranium de Hushan (湖山) en Namibie, qui détiennent la 3ème plus grosse réserve au monde, vont atteindre sa capacité de production maximale cette année avec 6 500 tonnes de brut par an. C'est le plus grand projet d'investissement chinois en Afrique.

Translated from French by

The Hushan uranium Mines (湖山) in Namibia, which hold the world's third largest reserve, will reach its maximum production capacity this year with 6 500 tonnes of crude per year. This is the largest Chinese investment project in Africa.

What I am concerned of these new openings is the risk of importing the poisonous financial "product" and its practice, namely the hedge founds and derivatives etc.

These practices are poisonous to everybody on the planet. To monitor, restrain and regulate such practices is no easy task, especially when the entity has most of its capital outside the regulator's jurisdiction. It is already hard to watch out the Chinese bankers, let along the American bankers.

These practices are poisonous to everybody on the planet. To monitor, restrain and regulate such practices is no easy task, especially when the entity has most of its capital outside the regulator's jurisdiction. It is already hard to watch out the Chinese bankers, let along the American bankers.

What I am concerned of these new openings is the risk of importing the poisonous financial "product" and its practice, namely the hedge founds and derivatives etc.

These practices are poisonous to everybody on the planet. To monitor, restrain and regulate such practices is no easy task, especially when the entity has most of its capital outside the regulator's jurisdiction. It is already hard to watch out the Chinese bankers, let along the American bankers.

Capital control stays. The funds will not be able to move money out of China easily

Jura The idiot

General

now noticed the article

China’s Vast Intercontinental Building Plan Is Gaining Momentum

Updated on April 10, 2018

China’s Vast Intercontinental Building Plan Is Gaining Momentum

Updated on April 10, 2018

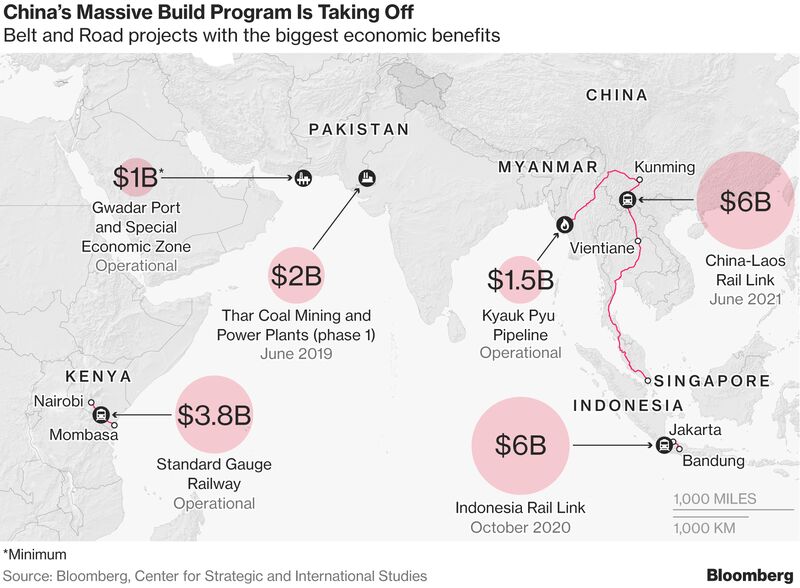

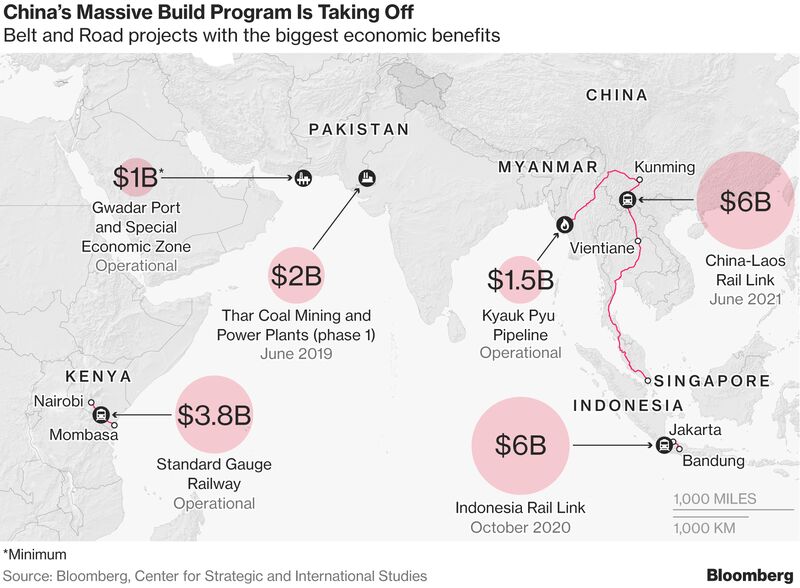

China’s massive build program to recreate trade routes stretching from Asia to Africa and Europe is gaining momentum.

Since President Xi Jinping’s flagship Belt and Road project was announced about five years ago, it gave impetus to billions of dollars of Chinese investment -- some of which were already in the pipeline for several years -- to build railways, roads, ports and power plants.

The program isn’t without controversy: debt is rising, an influx of Chinese workers has fueled tension with locals, and there are worries about China’s dominance in the region. And not all of the projects have succeeded.

“It’s been a mixed bag so far,” said Michael Kugelman, a senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. “There have certainly been success stories, and there will be more of them too, but there have also been setbacks.”

With many projects in various stages of developments, measuring the success and potential benefits can be tricky. Here’s a list of projects that analysts who track China’s Belt and Road investments say will provide the most economic impact to countries by unlocking trade routes:

Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu Pipeline

The $1.5 billion oil pipeline that runs from Kyaukpyu to Kunming last year, allowing crude supplies from the Middle East and Africa to reach China faster as shipments no longer need to be transported through the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea. The pipeline is designed to carry 22 million tons of crude a year, representing about 5 percent of China’s annual oil imports. Talks are also ongoing about building a $7.3 billion deep-water port, which would be China’s largest investment in the Southeast Asian nation. Along with a natural gas pipeline, the project represents an alternative route for energy imports and an important access point for goods shipped via the Indian Ocean, said Andrew Small, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, and author of “The China-Pakistan Axis.”

Pakistan’s Gwadar Port

Sharing a border with China, Pakistan has projects that are among the most developed of the Belt and Road Initiative. The and a 3,000 kilometer-long corridor of roads and railways links China with the Arabian Sea. Transshipment from the port has begun, giving China’s western Xinjiang province closer access to a port than Beijing. It’s located at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, just outside the Straits of Hormuz, near shipping routes that accommodate more than 17 million barrels of oil per day and a large quantity of bulk, break-bulk and containerized cargo. With China expected to increase oil imports from the Middle East, Gwadar is seen as a potential trade route, said Hasnain Malik, head of equities research at Exotix Capital in Dubai.

Asia Pacific Rail Links

China has a plan to connect Southeast Asian countries with the southwest region of Yunnan through a series of high-speed railways. There are three routes planned: a central one that runs through Laos, Thailand and Malaysia to reach Singapore; a western route through Myanmar; and an eastern one through Vietnam and Cambodia. Projects are at various stages of development, with construction on the and Laos legs already progressing. The plan represents some of the most important and high impact of China’s rail investments, said Small. In Indonesia, the $6 billion Jakarta-Bandung project is a flagship of President Joko Widodo’s infrastructure program and expected to the travel time between the two traffic-clogged cities to 40 minutes, from about three hours by car. The project has so far because of disputes over land clearance.

Kenya Railways

China is decrepit Colonial-era trains with new and faster ones in African countries from Ethiopia to Senegal. One of the key projects is the Standard Gauge Railway that links Kenya’s port city of Mombasa to landlocked neighbors including Rwanda and Uganda via a network of high speed lines. The $3.8 billion passenger and cargo link between Mombasa and Kenya’s capital Nairobi started last year. It cuts the journey time by about half to 5 hours, while also reducing the cost of transporting freight.

Pakistan is seeking to extract in the Thar desert at one of the world’s biggest known deposits of lignite, a lower-grade brown version of the fuel. The project includes the building of power plants to expand electricity capacity in a country that faces chronic shortages. The first phase, which will add 660 megawatts of power, will be completed next year and can be scaled to 5,000 megawatts to make it the largest cluster of electricity production in Pakistan.

Last week's article but a good read.

Trump’s Trade War Isn’t About Trade. It’s About Technology.

April 3, 2018

Over the last ten days, the Trump Administration has unveiled a grab bag of punitive measures directed at Chinese economic statecraft: tariffs on up to $60 billion worth of Chinese imports, accusations of intellectual property (IP) theft through hacking, restrictions on Chinese acquisitions in the United States, and a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint over China’s technology licensing laws.

The diversity of tools used (tariffs, investment restrictions, WTO cases) and activities targeted (imports, investment, and hacking) raised questions about the Trump administration’s underlying goals. Are these actions about reducing the bilateral trade deficit or stymying China’s technology ambitions? Are they aimed at protecting American IP or undermining Chinese industrial policy?

Compounding this confusion have been the mixed messages sent by the Trump administration. In announcing the tariffs, President Trump himself railed against the bilateral trade deficit and gave a quick nod to “.” But Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the man tasked with picking industries for those tariffs, has instead hammered away at Chinese industrial policy that seeks to acquire U.S. technology and use it to dominate key sectors.

While these positions aren’t mutually exclusive, there is a major difference between the remedies for a short-term trade imbalance (have China buy more U.S. goods) and the desire to maintain the United States’ long-term technological edge (prevent China from unfairly acquiring core U.S. technologies).

So what’s the real issue here, trade or technology? The answer, I believe, is found in the key policy document of the past month: the USTR Section 301 report. Both that document and the measures taken since its release indicate that, despite Trump’s own rhetoric, the main target here is Chinese industrial policy aimed at upgrading its technological infrastructure. Specifically, the latest actions seek to combat what is being viewed as Beijing’s concerted and coordinated efforts to acquire American technology in support of China’s “Made in China 2025” plan.

The Target: Made in China 2025

First approved by the State Council in 2015, Made in China 2025 is the Chinese government’s sweeping industrial policy that aims to indigenize certain technologies and establish technological leadership in ten key industries, including information technology, robotics, and new energy vehicles. After flying under U.S. policymakers’ radar the first couple years after its release, the plan is now emerging as a focal point of bilateral economic tensions.

Chinese industrial policies are dime a dozen, but what makes Made in China 2025 stand out is the breadth of its ambition, as well as the tactics employed to achieve its goals. If Made in China 2025 were to generally succeed, it would do for high-tech manufacturing what China did to low-cost manufacturing in the preceding two decades: vacuuming up a huge portion of global production and concentrating it in mainland China.

That has set off alarm bells for policymakers in several countries, and placed it at the center of recent economic frictions. In an , Lorand Laskai of the Council on Foreign Relations noted that the Section 301 report mentions or cites Made in China 2025 a full 116 times. before the Senate Committee on Finance, Lighthizer stated that he would like the tariffs to target the industries covered by Made in China 2025: “These are things that China listed and said we’re going to take technology, spend several hundred billion dollars and dominate the world. These are things that if China dominates the world, it’s bad for America.”

As my colleague Evan Feigenbaum , China’s pro-active approach to technological upgrading is nothing new and dates back to the 1950s, with the Chinese government consistently viewing cutting-edge technology as key to national power. But three things have changed the U.S. reaction to this round of Chinese industrial policymaking: (1) China now has the money to simply buy up cutting-edge American firms; (2) Made in China 2025 aims for Chinese firms to dominate not just domestic markets, but also global markets that America counts on; and (3) after decades of doubting China’s innovation potential, the United States now fears the rapid pace of China’s technological catch-up, and sees Chinese technology as a major (perhaps even existential) threat to U.S. economic competitiveness.

To see how those concerns are being translated into policy, I’ll first outline the contentions of the Section 301 report, and then show how the apparently disparate actions taken in its wake all seek to address specific concerns raised by the report.

The Report

President Trump initiated the Section 301 investigation last August, with the goal of determining whether Chinese government actions resulted in unfair or illegal acquisition of American IP. Released on March 22, the Section 301 investigation answered that question with an emphatic “yes.”

The report breaks down Chinese actions into four categories, each with its own dedicated section: forced technology transfers, discriminatory licensing requirements, overseas acquisitions, and illegal commercial hacking. But beyond a straightforward accounting of nefarious Chinese practices, the 182-page document is laced with a more significant argument: these actions are systematically undertaken in support of Chinese industrial policy goals, specifically Made in China 2025.

In the first section, the authors draw on surveys of U.S. firms to show that Chinese authorities require foreign firms to form joint ventures with Chinese companies and transfer valuable IP to them as a precondition to operating in China. The demands for technology transfers are often made indirectly or orally to avoid explicit violation of WTO rules that prohibit the practice. Though these transfers occur across a range of industries, they’ve been particularly onerous in industries targeted by Made in China 2025, like new energy vehicles and aviation.

The subsequent section on discriminatory licensing practices lays out Chinese laws that systematically discriminate against foreign firms licensing technology to Chinese companies. Among those rules is one requiring that after ten years of paying for licensing, the Chinese firm will be allowed to use the technology in perpetuity after the contract expires. These practices apply across the board for U.S. firms, not specifically to Made in China 2025 industries.

It’s in the third section, on overseas acquisitions, that the report’s authors make their strongest case. Spanning over 90 pages—nearly half of the entire report—the authors lay out how different Chinese government entities have shaped and funded a shopping spree of American technologies. It describes in detail Chinese acquisitions in strategic sectors highlighted by Made in China 2025, such as integrated circuits, robotics, aviation, and biotechnology. Many of those acquisitions involved government backing that worked against market forces or gave Chinese firms a financial edge in outbidding other buyers.

While these acquisitions by no means account for the entirety (or even the majority) of China’s multi-year outbound investment surge, they do paint a compelling picture of Chinese government support for non-market-driven purchases of key technologies that support Made in China 2025’s goals.

In the final major section, the report outlines the impact of commercial hacking originating from China that seeks to steal IP or trade secrets from U.S. companies. This section largely rehashes longstanding accusations of Chinese cyber corporate espionage, though it does highlight overlap between the U.S. industries targeted and those encouraged by Made in China 2025. It makes the argument that while these cyber attacks have declined substantially since 2014—with some of that decline attributed to a 2015 agreement between Presidents Obama and Xi—they still regularly occur and continue to damage American firms.

Trump’s Trade War Isn’t About Trade. It’s About Technology.

April 3, 2018

Over the last ten days, the Trump Administration has unveiled a grab bag of punitive measures directed at Chinese economic statecraft: tariffs on up to $60 billion worth of Chinese imports, accusations of intellectual property (IP) theft through hacking, restrictions on Chinese acquisitions in the United States, and a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint over China’s technology licensing laws.

The diversity of tools used (tariffs, investment restrictions, WTO cases) and activities targeted (imports, investment, and hacking) raised questions about the Trump administration’s underlying goals. Are these actions about reducing the bilateral trade deficit or stymying China’s technology ambitions? Are they aimed at protecting American IP or undermining Chinese industrial policy?

Compounding this confusion have been the mixed messages sent by the Trump administration. In announcing the tariffs, President Trump himself railed against the bilateral trade deficit and gave a quick nod to “.” But Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the man tasked with picking industries for those tariffs, has instead hammered away at Chinese industrial policy that seeks to acquire U.S. technology and use it to dominate key sectors.

While these positions aren’t mutually exclusive, there is a major difference between the remedies for a short-term trade imbalance (have China buy more U.S. goods) and the desire to maintain the United States’ long-term technological edge (prevent China from unfairly acquiring core U.S. technologies).

So what’s the real issue here, trade or technology? The answer, I believe, is found in the key policy document of the past month: the USTR Section 301 report. Both that document and the measures taken since its release indicate that, despite Trump’s own rhetoric, the main target here is Chinese industrial policy aimed at upgrading its technological infrastructure. Specifically, the latest actions seek to combat what is being viewed as Beijing’s concerted and coordinated efforts to acquire American technology in support of China’s “Made in China 2025” plan.

The Target: Made in China 2025

First approved by the State Council in 2015, Made in China 2025 is the Chinese government’s sweeping industrial policy that aims to indigenize certain technologies and establish technological leadership in ten key industries, including information technology, robotics, and new energy vehicles. After flying under U.S. policymakers’ radar the first couple years after its release, the plan is now emerging as a focal point of bilateral economic tensions.

Chinese industrial policies are dime a dozen, but what makes Made in China 2025 stand out is the breadth of its ambition, as well as the tactics employed to achieve its goals. If Made in China 2025 were to generally succeed, it would do for high-tech manufacturing what China did to low-cost manufacturing in the preceding two decades: vacuuming up a huge portion of global production and concentrating it in mainland China.

That has set off alarm bells for policymakers in several countries, and placed it at the center of recent economic frictions. In an , Lorand Laskai of the Council on Foreign Relations noted that the Section 301 report mentions or cites Made in China 2025 a full 116 times. before the Senate Committee on Finance, Lighthizer stated that he would like the tariffs to target the industries covered by Made in China 2025: “These are things that China listed and said we’re going to take technology, spend several hundred billion dollars and dominate the world. These are things that if China dominates the world, it’s bad for America.”

As my colleague Evan Feigenbaum , China’s pro-active approach to technological upgrading is nothing new and dates back to the 1950s, with the Chinese government consistently viewing cutting-edge technology as key to national power. But three things have changed the U.S. reaction to this round of Chinese industrial policymaking: (1) China now has the money to simply buy up cutting-edge American firms; (2) Made in China 2025 aims for Chinese firms to dominate not just domestic markets, but also global markets that America counts on; and (3) after decades of doubting China’s innovation potential, the United States now fears the rapid pace of China’s technological catch-up, and sees Chinese technology as a major (perhaps even existential) threat to U.S. economic competitiveness.

To see how those concerns are being translated into policy, I’ll first outline the contentions of the Section 301 report, and then show how the apparently disparate actions taken in its wake all seek to address specific concerns raised by the report.

The Report

President Trump initiated the Section 301 investigation last August, with the goal of determining whether Chinese government actions resulted in unfair or illegal acquisition of American IP. Released on March 22, the Section 301 investigation answered that question with an emphatic “yes.”

The report breaks down Chinese actions into four categories, each with its own dedicated section: forced technology transfers, discriminatory licensing requirements, overseas acquisitions, and illegal commercial hacking. But beyond a straightforward accounting of nefarious Chinese practices, the 182-page document is laced with a more significant argument: these actions are systematically undertaken in support of Chinese industrial policy goals, specifically Made in China 2025.

In the first section, the authors draw on surveys of U.S. firms to show that Chinese authorities require foreign firms to form joint ventures with Chinese companies and transfer valuable IP to them as a precondition to operating in China. The demands for technology transfers are often made indirectly or orally to avoid explicit violation of WTO rules that prohibit the practice. Though these transfers occur across a range of industries, they’ve been particularly onerous in industries targeted by Made in China 2025, like new energy vehicles and aviation.

The subsequent section on discriminatory licensing practices lays out Chinese laws that systematically discriminate against foreign firms licensing technology to Chinese companies. Among those rules is one requiring that after ten years of paying for licensing, the Chinese firm will be allowed to use the technology in perpetuity after the contract expires. These practices apply across the board for U.S. firms, not specifically to Made in China 2025 industries.

It’s in the third section, on overseas acquisitions, that the report’s authors make their strongest case. Spanning over 90 pages—nearly half of the entire report—the authors lay out how different Chinese government entities have shaped and funded a shopping spree of American technologies. It describes in detail Chinese acquisitions in strategic sectors highlighted by Made in China 2025, such as integrated circuits, robotics, aviation, and biotechnology. Many of those acquisitions involved government backing that worked against market forces or gave Chinese firms a financial edge in outbidding other buyers.

While these acquisitions by no means account for the entirety (or even the majority) of China’s multi-year outbound investment surge, they do paint a compelling picture of Chinese government support for non-market-driven purchases of key technologies that support Made in China 2025’s goals.

In the final major section, the report outlines the impact of commercial hacking originating from China that seeks to steal IP or trade secrets from U.S. companies. This section largely rehashes longstanding accusations of Chinese cyber corporate espionage, though it does highlight overlap between the U.S. industries targeted and those encouraged by Made in China 2025. It makes the argument that while these cyber attacks have declined substantially since 2014—with some of that decline attributed to a 2015 agreement between Presidents Obama and Xi—they still regularly occur and continue to damage American firms.

continued...

The Actions

In the wake of the Section 301 report’s release, the Trump administration has threatened various actions to address issues raised in the report: tariffs on $50 to $60 billion worth of Chinese goods, restrictions on Chinese investment in the United States, and a case at the WTO. At first glance these appear scattershot, and the public focus on tariffs has led many to mistakenly view this scuffle as centering on the trade deficit.

But upon closer examination, these moves largely target the four categories of unfair technology acquisition listed above: technology transfers, discriminatory licensing, overseas acquisitions, and hacking.

Category two—China’s licensing practices—is the target of the . It specifically challenges the Chinese law that grants Chinese entities the right to use foreign technology in perpetuity after a ten-year licensing contract expires.

Category three—Chinese acquisition of U.S. technology firms—is addressed by President Trump’s order for the Treasury Department to propose measures restricting Chinese investments. To that end, the Treasury Department is apparently of the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a law that would allow the president to block transactions or seize assets in the face of an “unusual and extraordinary threat.”

Whether the administration takes that action or not, stepped up scrutiny and legislative reforms to managing foreign direct investment in the United States are already on Chinese acquisitions. Both of these investment restrictions may paint with too broad a brush—blocking legitimate, purely commercial acquisitions of U.S. firms—but it seems that’s a price the administration is willing to pay for undermining Chinese industrial policy.

That leaves categories one and four: forced technology transfers and commercial hacking. Neither of these are as susceptible to the responses listed above. Demands for technology transfers are often made informally and between companies, making them hard to prosecute at the WTO. On a more fundamental level, the WTO was built to deal with more traditional barriers to trade, not the more nuanced world of protecting IP. Finally, commercial espionage is not something you can “block” like a Chinese acquisition of a U.S. company.

The Tariffs

So instead the administration has opted for tariffs, a punitive measure designed to exact an economic cost for Chinese behaviors that it deems predatory. In an attempt to send a more targeted message, Lighthizer has said Made in China 2025’s target industries.

Tariffs are an imperfect response for several reasons. It sends the wrong message (“trade war”), and also opens the United States up to a at the WTO for taking unilateral action. If the administration loses that challenge, it risks allowing China to position itself as a defender of free trade and existing norms, while the United States comes across as the bull in the China shop of international agreements. Or, if things really come to blows on the trade front, China may simply be able to exert enough targeted pressure on U.S. agriculture to require a favorable settlement. China’s recent imposition of on 128 categories of American goods, and the subsequent for American manufacturers, gave a first taste of what may lie ahead.

But, as Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has , an even more fundamental risk lurks: that President Trump will settle for a “pyrrhic victory” of a reduced trade deficit while letting the deeper issues of technology acquisition go uncorrected. In that world, China could drive a wedge between the president and USTR by appealing to Trump’s personal obsession with trade deficits, letting China buy its way out of a deeper challenge to its industrial policy with a couple hundred billion dollars of soybean imports and airplanes.

If the above tariffs result in a protracted and painful trade war, that “pyrrhic victory” of increasing U.S. exports to China could end up looking like an appealing outcome to President Trump. But given the realities outlined in the report that the President himself commissioned, it’s one he should not choose.

The Actions

In the wake of the Section 301 report’s release, the Trump administration has threatened various actions to address issues raised in the report: tariffs on $50 to $60 billion worth of Chinese goods, restrictions on Chinese investment in the United States, and a case at the WTO. At first glance these appear scattershot, and the public focus on tariffs has led many to mistakenly view this scuffle as centering on the trade deficit.

But upon closer examination, these moves largely target the four categories of unfair technology acquisition listed above: technology transfers, discriminatory licensing, overseas acquisitions, and hacking.

Category two—China’s licensing practices—is the target of the . It specifically challenges the Chinese law that grants Chinese entities the right to use foreign technology in perpetuity after a ten-year licensing contract expires.

Category three—Chinese acquisition of U.S. technology firms—is addressed by President Trump’s order for the Treasury Department to propose measures restricting Chinese investments. To that end, the Treasury Department is apparently of the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a law that would allow the president to block transactions or seize assets in the face of an “unusual and extraordinary threat.”

Whether the administration takes that action or not, stepped up scrutiny and legislative reforms to managing foreign direct investment in the United States are already on Chinese acquisitions. Both of these investment restrictions may paint with too broad a brush—blocking legitimate, purely commercial acquisitions of U.S. firms—but it seems that’s a price the administration is willing to pay for undermining Chinese industrial policy.

That leaves categories one and four: forced technology transfers and commercial hacking. Neither of these are as susceptible to the responses listed above. Demands for technology transfers are often made informally and between companies, making them hard to prosecute at the WTO. On a more fundamental level, the WTO was built to deal with more traditional barriers to trade, not the more nuanced world of protecting IP. Finally, commercial espionage is not something you can “block” like a Chinese acquisition of a U.S. company.

The Tariffs

So instead the administration has opted for tariffs, a punitive measure designed to exact an economic cost for Chinese behaviors that it deems predatory. In an attempt to send a more targeted message, Lighthizer has said Made in China 2025’s target industries.

Tariffs are an imperfect response for several reasons. It sends the wrong message (“trade war”), and also opens the United States up to a at the WTO for taking unilateral action. If the administration loses that challenge, it risks allowing China to position itself as a defender of free trade and existing norms, while the United States comes across as the bull in the China shop of international agreements. Or, if things really come to blows on the trade front, China may simply be able to exert enough targeted pressure on U.S. agriculture to require a favorable settlement. China’s recent imposition of on 128 categories of American goods, and the subsequent for American manufacturers, gave a first taste of what may lie ahead.

But, as Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has , an even more fundamental risk lurks: that President Trump will settle for a “pyrrhic victory” of a reduced trade deficit while letting the deeper issues of technology acquisition go uncorrected. In that world, China could drive a wedge between the president and USTR by appealing to Trump’s personal obsession with trade deficits, letting China buy its way out of a deeper challenge to its industrial policy with a couple hundred billion dollars of soybean imports and airplanes.

If the above tariffs result in a protracted and painful trade war, that “pyrrhic victory” of increasing U.S. exports to China could end up looking like an appealing outcome to President Trump. But given the realities outlined in the report that the President himself commissioned, it’s one he should not choose.

What I am concerned of these new openings is the risk of importing the poisonous financial "product" and its practice, namely the hedge founds and derivatives etc.

These practices are poisonous to everybody on the planet. To monitor, restrain and regulate such practices is no easy task, especially when the entity has most of its capital outside the regulator's jurisdiction. It is already hard to watch out the Chinese bankers, let along the American bankers.

It seems China realises what you mentioned and are planning things out:

China to peer inside its shadow banking world via a new database

The new statistics platform is to measure all financial activity, from leveraged securities investment to local government borrowing, the People’s Bank of China said

Beijing will establish a data bank in support of its campaign to clean up its unruly shadow banking system and control financial risk as it continues to learn from the lessons of the stock market turmoil of 2015.

In its latest assault on financial activity conducted by unregulated institutions, the government will set up a statistics platform that will measure all financial activity, from leveraged securities investment to local government borrowing, the People’s Bank of China said on Monday.

The move significantly advances the Chinese government’s endeavour to get at the root of the 2015 stock market meltdown – grey-market margin lending beyond the purview of regulators, including by shadow banks. "

It’s now open season on ‘big crocs’: why Xi targets China’s particular breed of oligarchs

The rich and powerful who pull strings behind the scenes in Beijing have much in common with their Russian counterparts, but the government seems intent on trying to halt their clandestine activities

In China, the equivalents of Russian oligarchs are known as “big crocs”. True to their monikers, they enjoy lurking in shadows and pulling strings below the surface.

Rising through the booming but corruption-ridden 1990s and 2010s, they have deliberately kept their business background vague and business empires opaque, which have lent a dash of mystery to their legendary standings in China’s private sector.

Almost without exceptions, they boast impeccable political connections, often directly to the highest echelon of power in Beijing, through marriage, acting as front men for the powerful political families or agents for the all-powerful clandestine intelligence services, or using bribes to have relatives and families of the Chinese leaders in their pockets.

With political backing and their own acumen, many have joined the elite ranks of tycoons with assets worth 1 trillion yuan and beyond. They are known for their ability to “summon wind and rain” in deal making and playing the financial markets as well as stealing state assets, raising funds through illegal pyramid schemes, or securing cheap land or easy bank loans.

Just as they tried to duplicate their shenanigans on major overseas mergers and acquisitions with the eye to move massive funds abroad for safety, their shady pasts have caught up with them and their empires have started to unravel in a dramatic fashion in the past year.