Over the past decade, China’s once-pollution-choked skies have steadily improved, according to more than two decades of atmospheric measurements taken by NASA satellites.

Each year, air pollution is responsible for more than four million premature deaths globally — including an estimated one million in China — primarily from heart disease, lung cancer and respiratory illnesses. Fine particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres or less — referred to as PM2.5 — is the most concerning air pollutant.

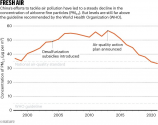

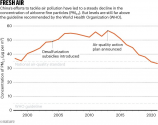

Since 2013, PM2.5 levels have steadily declined, and in 2021, the average annual exposure was 33.3 micrograms per cubic metre (see ‘Fresh air’). That’s below the nation’s air-quality standard of 35.

In 2021, the WHO lowered its recommended annual-exposure limit for PM2.5 from 10 to 5 micrograms per cubic metre, a level that China, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States and Canada, exceed.

The decline in PM2.5 is the result of targeted efforts by China over the past two decades to address poor air quality. Upgrades to coal-fired power plants have had the biggest effect so far, says Qiang Zhang, an atmospheric scientist at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Since 2004, the Chinese government has provided subsidies to retrofit smokestacks in coal-fired power plants with filters and other equipment to remove sulfur dioxide — a molecule that reacts with other compounds in the atmosphere to form PM2.5 particles — from emissions.

In 2013, China released its air-pollution prevention and control action plan, which further tightened standards for industrial emissions, and shut down small, inefficient power generators and industrial operators.

An analysis by Zhang and his colleagues shows that these measures accounted for 81% of the reductions to PM2.5 emissions between 2013 and 2017

.

Further reductions could lead to fewer heavy-pollution days — driven by industrial emissions and cold weather that prevents dispersal — when the daily PM2.5 concentration can exceed 200 micrograms per cubic metre. Last year, China’s government set a target to eliminate heavy-pollution days by 2025.

“Energy and the climate policies would definitely play more important roles in the future,” he says. These include efforts to supply more households with natural gas or electric heating systems in parts of rural China that still rely on coal and wood-fired stoves to heat their homes.

Electrical grids in rural areas are being upgraded to accommodate the increased capacity required for domestic heating, says Zhang, and the renewable-energy sector is expanding. But, “it’s still a long way to go”, before coal-fired power is replaced, he says.