Despite mounting frustration here, a wary Pentagon has blown past a 60-day window imposed by Congress to deliver a plan for a long-debated East Coast ballistic missile interceptor site.

The Pentagon has long worried about the multi-billion dollar price tag that comes along with building a new interceptor field and its infrastructure, and has generally had little to say to lawmakers demanding answers. The Missile Defense Review released earlier this year also called into question the need to build a third domestic interceptor field.

But that hasn’t stopped Congressional delegations from New York, Ohio, and Michigan — the states with locations still in the running for any future work — from demanding answers. And they want those answers before the 2020 defense budget markups begin.

“Our congressional intent was very clear,” Rep. Elise Stefanik, a Republican who represents the New York location at Fort Drum, admonished Missile Defense Agency chief Lt. Gen. Samuel Greaves Wednesday. “The environmental impact study was funded and authorized by Congress. That has been completed. The Secretary of Defense sat in this very committee room and said on record, under oath, that he would meet our request to voluntarily provide that information to Congress.”

The 2018 NDAA

60 days after the delivery of the Missile Defense Review to submit a location to Congress. The review was released in January. But the document also said it was kicking off a series of six-month reviews on what might be need to be set up or modernized to meet missile threats.

“Let me make it perfectly clear,” Stefanik added. “Our expectation is that we will hear from the Secretary of Defense what the preferred site is.”

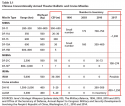

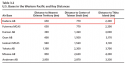

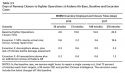

The sites still under consideration are the Fort Custer Training Center in Augusta, Mich., Camp Garfield in Ohio, and Fort Drum, NY.

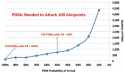

The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2012 that it would cost $3.6 billion over five years to build the site and buy 20 interceptors, but that doesn’t include upkeep and sustainment costs.

The Missile Defense Agency “has repeatedly stated that the estimated $3-$4 billion cost to build such a site would be better spent on improving the capabilities of the existing [Ground-based Midcourse Defense] system,” said Kingston Reif, director for Disarmament and Threat Reduction Policy at the Arms Control Association. “That the Pentagon punted, at least for now, on this issue goes to show how expensive and rightly controversial it is.”

Proponents of the third site had a brief glimmer of hope on May 1 however, when Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan — who was

on Thursday — told Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan, a Democrat whose district includes the Ohio site that he would give him an answer “today.”

But that answer never came. A congressional staffer told me the DoD informed lawmakers Shanahan “misspoke” and “no decision has been made or will be made until the Trump Administration first determines whether an East Coast Missile Defense site is even necessary.”

Asked to clarify matters, a Pentagon spokesperson said the only statement the department would make is already in January’s Missile Defense Review, referring questions to the Missile Defense Agency. Mark Wright, spokesman for the agency, said via email, “at this time, I don’t have anything to add beyond what the Missile Defense Review has already said about this.”

So, what does the

? Essentially, the Pentagon isn’t ready to make a decision. Since the Pentagon has already wrapped up its environmental study of the three sites, that work “will enable DoD to shorten the deployment timeline should the United States determine that threat conditions warrant building a new interceptor site. In the event of such a decision, the location selected for the site will be informed by multiple pertinent factors at the time.”

But there are options other than building a brand-new base, says Tom Karako, director of the Missile Defense Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“If you want to replicate Fort Greely,” which already houses 26 interceptors, “you’re looking at several billion dollars of infrastructure,” which the Pentagon might not have the stomach for.

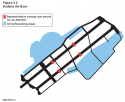

Instead, the US should consider a transportable option with a small footprint for an East Coast missile defense capability, Karako said. It would use the same interceptors that are in the ground in Alaska and California but be truck-mounted so it can move between locations. Going mobile would carry a price tag “in the millions and not in the billions, plus you’re not tied to a particular location.”

But Congressional delegations want infrastructure spending in their districts, something the mobile systems wouldn’t provide. To put it more baldly, lawmakers want money spent in their districts where their constituents would benefit.

In a March 26 letter sent to Shanahan by the Ohio delegation, lawmakers pointed out that if their site were selected, it would bring 2,300 construction jobs to the presidential battleground state, along with up to 850 full-time employees.

Rep. Mike Turner, ranking member of the House Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee, told Greaves this week he’s ready for a decision.

“You have three communities that are vying for this — two need to be let go,” the Republican said. “Two need to be able to be told they can stand down, and their communities and their chambers of commerce and everybody else who’s working to advocate for their community needs to understand that actually a decision has been made because you’ve completed all the data work necessary for that decision.”