You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

US F/A-XX and F-X 6th Gen Aircraft News Thread

- Thread starter Jeff Head

- Start date

Brumby

Major

The reason for the scaling back in funds is because a different approach is being taken with the NGAD. The traditional approach with the NGAD of having a new platform is basically gone. Instead the approach is to push out new technologies as they mature rather than the emphasis of a platform centric development pathway. The immediate pathway I see is more likely than not of putting adaptive engine, laser or incorporating wingmen onto an F-35 platform rather than having a new platform.

The complete article from AWST is behind paywall. I am sharing it for the benefit for those who have no access.

The complete article from AWST is behind paywall. I am sharing it for the benefit for those who have no access.

Jun 14, 2019 | Aviation Week & Space Technology

For nearly a year, a chorus of U.S. Air Force leaders has promised to take an unconventional approach to the secretive program charged with delivering a new generation of advanced fighter capabilities, and now, it seems, the chiefs really mean it.

The Air Force last month completed an analysis of alternatives for the Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program, a milestone that normally precedes a dramatic spending ramp-up as requirements are defined and the competitive phase of the acquisition process begins.

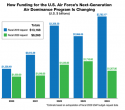

Instead, the Air Force switched gears and chopped $6.6 billion from the long-term spending plan for the capabilities that fall under the umbrella of the NGAD program.

The previously unreported 50.5% gash in the five-year budget for NGAD—which some lawmakers since have voted to accelerate—also comes as the Navy disavows the possibility of a joint airframe development program.

The funding and organizational moves make it clear the NGAD program will not follow the Pentagon’s established and, arguably, unreliable template for ushering in a state-of-the-art combat aircraft, from design through development and into service.

“NGAD is postured to shatter the acquisition paradigm that traditionally invests in a large monolithic program over many years,” an Air Force spokesperson told Aviation Week. “Instead, NGAD is investing in technologies and prototypes that have produced results and demonstrated promise.”

For several years, prospective contractors have teased concepts for new combat aircraft. It often is depicted by drawings of a tailless, or nearly tailless, and stealthy airframe. There is usually, but not always, a cockpit for a human operator. Hints of new and exotic capabilities abound, such as an onboard defensive laser weapon and modular payloads.

Although the concept of a penetrating, next-generation fighter still appears in government documents, no such aircraft exists in the Air Force’s current plans for the NGAD program.

“We’re not trying to field a next-generation aircraft,” then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson told reporters in mid-May. “We are trying to advance critical technologies which might lead to next-generation aircraft.”

Wilson’s comments echo the results of a three-year, internal study called the Air Superiority 2030 Flight Plan, an unclassified summary of which was released in 2016. After concluding the Air Force’s existing force structure is “not capable of fighting and winning” against a classified set of potential adversary threats expected to emerge by 2030, the report’s authors warned the Air Force’s leadership to avoid a conventional acquisition plan.

“The Air Force must reject thinking focused on ‘next-generation’ platforms,” says the 2016 report by the Air Superiority 2030 Enterprise Capability Collaboration Team (ECCT).

Brumby

Major

continuation of the article due to word limit.

That language betrays a distrust of the ’s conventional acquisition approach, which starts with defining a mission in an environment perhaps a decade or more into the future. After forecasting the likely capabilities an adversary may have deployed by that time period, the Pentagon’s planners then craft detailed requirements for an aircraft that possesses all of the specific technologies required to defeat those capabilities upon entering service a decade later.

The ECCT recommended flipping the process around. Instead of starting with a desired end-state at a specific time, the ECCT called for launching the program by investing in the underlying, discrete technologies. As they are proven mature through prototyping, they can be transitioned into operational service, one by one, if necessary. It is a stark departure from a development program like the . The twin-engine fighter remains the world’s most powerful 13 years after it entered service, but the difficulty of pushing the state of the art in airframe, propulsion and mission systems at the same time caused the program to fall years behind schedule and go billions over budget.

“One of the mistakes I think people make on huge development programs is they put too many miracles in the program plan,” Wilson said in mid-May. “If one of them doesn’t work, you have a failed program.”

Despite echoing the Air Force’s three-year-old strategic plan, it took longer than expected for the Air Force budget to reflect Wilson’s description. In written testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee in the spring of 2017, Air Force acquisition officials described plans to develop a mix of “fifth-sixth-generation” aircraft for the Penetrating Counter-Air (PCA) mission.

A year later, the Air Force appeared to finalize a plan for spending $13.2 billion in fiscal 2020-24 on R&D for the NGAD program. The annual investment would rise to $3.78 billion in fiscal 2024 from $1.36 billion in fiscal 2020, according to budget justification documents released in May 2018. It was a significant spending ramp-up to support early development of PCA technologies, totaling 62% of the Air Force’s $21.4 billion development contract for the B-21.

But the NGAD budget plan still made some top Air Force acquisition leaders uncomfortable. Four months after the details of the 2018 spending plan were released, Will Roper, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, told journalists the NGAD program was shifting. Instead of a “single addition” to the PCA mission, the NGAD program was moving toward a strategy based on a “portfolio” of capabilities.

Five months later, Roper’s position had hardened still more. Speaking to reporters in February, he described the acquisition strategy by invoking the example of the “Century Series” of supersonic jet fighters introduced during the 1950s, each with different strengths and capabilities.

“Can you imagine how disruptive it would be if we could create a new airplane or a new satellite every 3-4 years?” Roper asked.

In April, the Air Force submitted written testimony to the same Senate committee, describing NGAD in completely different terms than only two years earlier. All references to the PCA mission and a “fifth-sixth-generation” fleet mix had disappeared. Instead, the NGAD represented the pursuit of a “family of capabilities.”

The Air Force’s new long-term spending plan reflects the new NGAD strategy. Instead of spending $13.2 billion in fiscal 2020-24, the Air Force now plans to spend $6.6 billion. The Air Force’s budget justification documents described the 50% cut as a spending deferral. Meanwhile, the Air Force would move forward on the “most promising classified technologies, which improve lethality by providing expanded capabilities.”

The details of the halved budget for NGAD remain classified, but Air Force officials have provided a thorough description of several elements. The focus now is on developing a “next-generation open-mission-system architecture, advanced sensors, cutting-edge communications using open standards and integration of the most promising technologies into the family of capabilities,” the Air Force said in submitted testimony to the Senate this year.

Meanwhile, the Air Force in fiscal 2021 plans to wrap up a $2.24 billion investment in new engine development for multiple combat aircraft applications. The goal is to demonstrate flight-weight prototypes of engines with a three-stream airflow architecture for greater fuel efficiency, plus introduce more thermal capacity and overall reliability. and Pratt & Whitney are developing competitive engine cores under the program. Although new cores—dubbed the XA100 and XA101—could be ready for transition to a new aircraft development after fiscal 2021, the changes to the NGAD budget suggest there could be a lengthy delay beyond the end of the Advanced Engine Transition Program.

Even less clear is the status of new missile programs under the NGAD program. The fiscal 2018 budget proposal introduced a line item for an “Air Dominance Air-to-Air Weapon,” with an annual $20 million outlay in fiscal 2020-23. But the latest spending plan deleted all funding for the year-old program, suggesting it has been classified or canceled.

Other concepts for next-generation counter-air missiles are just as nebulous. The 2018 budget included funding for a concept called the Long-Range Engagement Weapon (LREW). A separate presentation by a senior Pentagon official depicted the LREW as a two-stage missile launched from an F-22 weapon bay. But the latest two budget proposals provided funding for a program under the LREW name, which apparently is a project.

Similarly, no reference to the Small Advanced Capabilities Missile (SACM) appears in the latest spending plan, but the SACM concept has been rebranded as the Counter-Air Science and Technology (CAST) project within the Air Force Research Laboratory. It also has received a broader objective: Instead of designing SACM as half the size of an AIM-120D Amraam with the same range, the goal of CAST now is to apply the same range-extending technology to missiles of multiple sizes.

continuation of the article due to word limit.

Welp. No NGAD. This will get cancelled by the next administration with little to no progress. At least we'll have wildly obsolete F-15EXs!

TerraN_EmpirE

Tyrant King

So sounds like my predictions.

F15EX to replace F15C before the wings fall off.

F35D,E and F

And hopefully maybe a super raptor.

F15EX to replace F15C before the wings fall off.

F35D,E and F

And hopefully maybe a super raptor.

And hopefully maybe a super raptor.

Why do you think a super raptor?

TerraN_EmpirE

Tyrant King

Because retrofit of the same technology into F35 should allow retrofit into F22. Both platforms are targeted to a life span into beyond 2060s.

Brumby

Major

So sounds like my predictions.

F15EX to replace F15C before the wings fall off.

F35D,E and F

And hopefully maybe a super raptor.

My understanding of the DOD strategic game plan is much broader in perspective and the platforms that we are familiar with are just minor pieces in the chess board.

In a high end fight, the DOD's view is that it will be in three areas : space, communications, and battle management systems. NGAD is just a piece in the puzzle.

All those wonderful autonomous, manned systems, sensors and shooters are linked via communications. If you disable the coms you basically undermine the whole warfighting capabilities. Communications are basically space based and that will be where the fight will become. Underpinning the warfighting capabilities is via networked fused systems that will be increasingly be AI based and will rely on some sort of capable management systems that are up to the task of speed, processing capabilities, and latency while operating in a dense electronic environment. CEC and sensor fusion is just the beginning.

TerraN_EmpirE

Tyrant King

Which is a generals way of saying don’t worry we got this.

TerraN_EmpirE

Tyrant King

Look my point is, What was the reason the USAF is buying F15EX? Because the hardware on hand the F15C fleet is aging out to fast.

People who are critical of fifth gens talk about the cost of maintenance and readiness rates favoring their preferred 4th gens well in the case of F15C that maintenance cost is in the next decade to sky rocket well readiness drops through the floor.

Since Raptor buys were cut early F15 is aging out. hence F15EX.

At some point it will come back to hardware and numbers.

Autonomous system are nice and I trust them for AEW, ISR, Signt/Elint, Tanker, Strike even transport but air to air engagement or CAS?

F35 was designed as a strike fighter. It’s main mission set is and will remain air to ground with a degree of air to air.

F22 was designed first for Air supremacy with a light degree of strike it can do air to ground but is meant to compliment strike fighters which is what F35 is.

To use your chess analogy F35is the rook F22 the queen.

F35 keeps the enemy from going low F22 kills from on high.

Space based systems are important Absolutely they are like the Bishop of the board. But you need all the prices of the same with a degree of ability to take losses. Drones and autonomous are supposed to be the pawns. You can loose some as a write off.

They are low value reduced capacity compared Knights, Queen, Bishop and Rook. A pawn can only replace a queen in the right place and right situation.

When Generals start talking about space based systems and the puzzle what they are doing is basically wowing with bullship.

They are saying they don’t have the answers on the topic or don’t want to give one so they zoom out and start waxing poetic. As it’s to far from now to have solid grounds on details like numbers, capabilities, objective performance, cost and beyond a rough timeline.

People who are critical of fifth gens talk about the cost of maintenance and readiness rates favoring their preferred 4th gens well in the case of F15C that maintenance cost is in the next decade to sky rocket well readiness drops through the floor.

Since Raptor buys were cut early F15 is aging out. hence F15EX.

At some point it will come back to hardware and numbers.

Autonomous system are nice and I trust them for AEW, ISR, Signt/Elint, Tanker, Strike even transport but air to air engagement or CAS?

F35 was designed as a strike fighter. It’s main mission set is and will remain air to ground with a degree of air to air.

F22 was designed first for Air supremacy with a light degree of strike it can do air to ground but is meant to compliment strike fighters which is what F35 is.

To use your chess analogy F35is the rook F22 the queen.

F35 keeps the enemy from going low F22 kills from on high.

Space based systems are important Absolutely they are like the Bishop of the board. But you need all the prices of the same with a degree of ability to take losses. Drones and autonomous are supposed to be the pawns. You can loose some as a write off.

They are low value reduced capacity compared Knights, Queen, Bishop and Rook. A pawn can only replace a queen in the right place and right situation.

When Generals start talking about space based systems and the puzzle what they are doing is basically wowing with bullship.

They are saying they don’t have the answers on the topic or don’t want to give one so they zoom out and start waxing poetic. As it’s to far from now to have solid grounds on details like numbers, capabilities, objective performance, cost and beyond a rough timeline.