You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Trade War with China

- Thread starter Ultra

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Jura The idiot

General

now I read

Will China use its US$1.2 trillion of US debt as firepower to fight the trade war?

Will China use its US$1.2 trillion of US debt as firepower to fight the trade war?

- Fears are mounting among investors and analysts of potential adverse effects on global economic growth as China promises to strike back after US raised tariffs on Friday

- Uncertainties on how escalating tensions will unravel have hurt markets this week

China’s promise to strike back after US president Donald Trump increased tariffs on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods on Friday has heightened uncertainty on how escalating trade tensions between the two countries will unravel and raised fears among investors and analysts of worst-case scenarios that will hurt global growth.

If China was unwilling to play ball on Trump’s terms, Beijing, analysts said, not only could retaliate by imposing countervailing tariffs of its own, but it also has a range of financial arsenal power at its disposal to punish the US.

For starters, China could fire back by dumping its vast holdings of US government debt. Flooding the market with treasuries would push down US bond prices and cause the yields to spike. That would make it more costly for US companies and consumers to borrow, in turn depressing America’s economic growth.

Cliff Tan, East Asian head of global markets research at MUFG Bank said it was unlikely that China would choose to scale back its holdings in US treasuries sharply as that would hurt its own interests and fuel “extreme” market volatility.

“Dumping treasuries would be an ineffective weapon for China as that would send yields higher and hurt the positions of their own holdings in treasuries,” said Tan.

“If China got out of US dollar assets completely, it would be very risky to them because of extreme market volatility.”

The trade war had seemed on the cusp of ending until Sunday when Trump threatened to raise existing tariffs in a tweet, sending Chinese stocks and its currency lower this week. The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index touched its lowest level in 10 weeks while the yuan is heading for its biggest weekly decline since mid-2018.

Minutes after the US raised tariffs from 10 per cent to 25 per cent on Friday, the Ministry of Commerce reiterated its tough stance in the trade war, saying in a statement, “we’ll have no choice but to take the necessary countermeasures”.

Nonetheless, the statement said Beijing remained hopeful to resolve the problem “through cooperation and negotiations”. Vice-Premier Liu He has been in Washington since Thursday for two-day of trade talks. Talks will resume on Friday morning in Washington.

Up until 2016, the People’s Bank of China was buying US dollars from exporters while selling yuan to them to prevent the Chinese currency’s excessive appreciation. Most of China’s US$3.1 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, the world’s largest, is parked with US Treasury securities, which have a safe haven status. China needs the US dollar assets as a safety buffer should it need to bail out the domestic banking system or to support the yuan through foreign exchange intervention.

Although it has cut its holdings in US Treasuries in recent years, it still takes the top spot among foreign creditors at US$1.123 trillion, followed by Japan with US$1.042 trillion.

The amount, however, is only around 5 per cent of the US’ total debt of US$22 trillion owed by the federal, state and local governments as of February. Of the total, more than US$5 trillion debt is actually owned by the federal government in trust funds dedicated to social security. Much of the rest of the debt is owned by individual investors, corporations and other public entities, including the Chinese government.

Although US$1.123 trillion is by no means a small amount, it accounts for just around 5 per cent of the US’ national debt and remains to be seen if China’s paring back of its holdings would lead to any effective results.

“Dumping treasuries is unlikely to be an effective move for trade war negotiations. China is unlikely to find alternative investment options given that it holds so much treasuries,” said Betty Rui Wang, senior China economist at ANZ Bank.

Still, if China decided to sell US treasuries and bought oil, oil producers who receive the US dollars may channel them back into US treasuries, which would not increase China’s leverage to protect its interests.

MUFG’s Tan said a better option for China would be to allow the yuan to depreciate against the US dollar to offset the negative impact of the tariffs.

But this week’s decline in the yuan’s exchange rate dashed hopes that Beijing would fulfil US demands to keep its currency stable at all costs.

“If there is no currency stability pact negotiated, then this is certainly one way China can prepare for what we think is going to be pretty serious escalation of tariffs,” Tan said.

The latest round of tariff increase to 25 per cent by the Trump administration now matches the rate imposed on a prior US$50 billion category of Chinese machinery and technology goods. Trump has also threatened 25 per cent tariffs on possibly another US$300 billion worth of Chinese goods.

Equation

Lieutenant General

Yes but Trump know's that he NEED his voting bases in order to get re elect as POTUS. These racist Trump voting base felt empower by his tweets and tough images that has embolden them to more public racist rants at minorities and so forth.No. It’s language that resonates with his voter base. And speaks to who they are.

Jura The idiot

General

several "retweets":

·

We have lost 500 Billion Dollars a year, for many years, on Crazy Trade with China. NO MORE!

·

Talks with China continue in a very congenial manner - there is absolutely no need to rush - as Tariffs are NOW being paid to the United States by China of 25% on 250 Billion Dollars worth of goods & products. These massive payments go directly to the Treasury of the U.S....

....The process has begun to place additional Tariffs at 25% on the remaining 325 Billion Dollars. The U.S. only sells China approximately 100 Billion Dollars of goods & products, a very big imbalance. With the over 100 Billion Dollars in Tariffs that we take in, we will buy.....

....agricultural products from our Great Farmers, in larger amounts than China ever did, and ship it to poor & starving countries in the form of humanitarian assistance. In the meantime we will continue to negotiate with China in the hopes that they do not again try to redo deal!

·

Tariffs will bring in FAR MORE wealth to our Country than even a phenomenal deal of the traditional kind. Also, much easier & quicker to do. Our Farmers will do better, faster, and starving nations can now be helped. Waivers on some products will be granted, or go to new source!

·

Tariffs will make our Country MUCH STRONGER, not weaker. Just sit back and watch! In the meantime, China should not renegotiate deals with the U.S. at the last minute. This is not the Obama Administration, or the Administration of Sleepy Joe, who let China get away with “murder!”

·

We have lost 500 Billion Dollars a year, for many years, on Crazy Trade with China. NO MORE!

·

Talks with China continue in a very congenial manner - there is absolutely no need to rush - as Tariffs are NOW being paid to the United States by China of 25% on 250 Billion Dollars worth of goods & products. These massive payments go directly to the Treasury of the U.S....

....The process has begun to place additional Tariffs at 25% on the remaining 325 Billion Dollars. The U.S. only sells China approximately 100 Billion Dollars of goods & products, a very big imbalance. With the over 100 Billion Dollars in Tariffs that we take in, we will buy.....

....agricultural products from our Great Farmers, in larger amounts than China ever did, and ship it to poor & starving countries in the form of humanitarian assistance. In the meantime we will continue to negotiate with China in the hopes that they do not again try to redo deal!

·

Tariffs will bring in FAR MORE wealth to our Country than even a phenomenal deal of the traditional kind. Also, much easier & quicker to do. Our Farmers will do better, faster, and starving nations can now be helped. Waivers on some products will be granted, or go to new source!

·

Tariffs will make our Country MUCH STRONGER, not weaker. Just sit back and watch! In the meantime, China should not renegotiate deals with the U.S. at the last minute. This is not the Obama Administration, or the Administration of Sleepy Joe, who let China get away with “murder!”

Hendrik_2000

Lieutenant General

Talk end with no agreement but keep the channel of communication open. Meanwhile Chinese stock market jump higher

U.S., China Lack Deal But Avoid Rupture After Tariff Hike

Saleha Mohsin, Ye Xie and Shawn Donnan,Bloomberg 12 minutes ago

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. and Chinese officials wrapped up high-level trade talks on Friday, lacking a deal yet avoiding a breakdown in negotiations even after President Donald Trump boosted tariffs on $200 billion in goods from China and threatened to impose more.

The U.S. gave its bottom line in talks in Washington, saying Beijing had three to four weeks more to reach an agreement before the Trump administration enacts additional tariffs on $325 billion of Chinese imports not currently covered by punitive duties, according to two people familiar with the talks.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin described Friday’s discussions as constructive as he left the U.S. Trade Representative’s office. Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, the top negotiator who led the talks in Washington, told reporters at his hotel that the talks went “fairly well.”

Yet several people familiar with the discussions said little progress was made during a working dinner on Thursday and in Friday morning talks. Liu didn’t come prepared to offer much more in the way of concessions, one of the people said.

Liu and his delegation were expected to leave Washington on Friday afternoon, according to a person familiar with their planning.

U.S. stocks fell for a fifth day on Friday, though they climbed from lows of the day after indications from American officials that the two sides will keep talking.

No Rush

Earlier Friday, Trump said there’s “no need to rush” a deal. “Talks with China continue in a very congenial manner -- there is absolutely no need to rush,” the U.S. president said on Twitter, before talks resumed. “In the meantime we will continue to negotiate with China in the hopes that they do not again try to redo deal!”

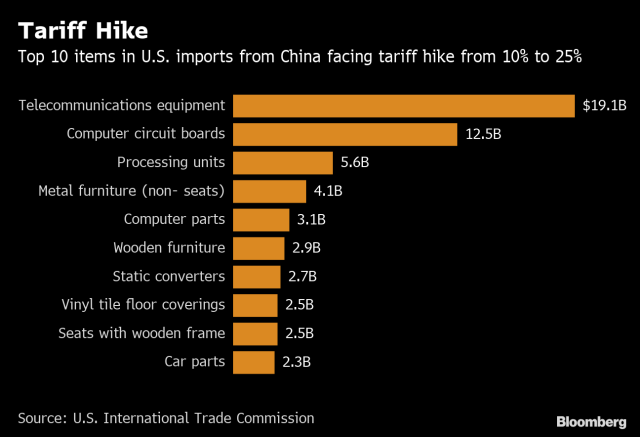

Amid the latest talks, the U.S. moved ahead with plans on Friday to increase the punitive tariff to 25% from 10% on 5,700 different product categories from China -- ranging from cooked vegetables to Christmas lights and highchairs for babies. China said it will be forced to retaliate, though the government didn’t immediately specify how.

The fresh wave of U.S. tariffs marked a sharp reversal from just last week, when U.S. officials expressed optimism that a pact was within reach. The escalation with China also signaled Trump’s willingness to risk more economic and political damage on his apparent belief that trade wars ultimately are winnable.

Meanwhile Chinese stock market jump higher

What trade war? China stocks jump after tariff hike

U.S., China Lack Deal But Avoid Rupture After Tariff Hike

Saleha Mohsin, Ye Xie and Shawn Donnan,Bloomberg 12 minutes ago

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. and Chinese officials wrapped up high-level trade talks on Friday, lacking a deal yet avoiding a breakdown in negotiations even after President Donald Trump boosted tariffs on $200 billion in goods from China and threatened to impose more.

The U.S. gave its bottom line in talks in Washington, saying Beijing had three to four weeks more to reach an agreement before the Trump administration enacts additional tariffs on $325 billion of Chinese imports not currently covered by punitive duties, according to two people familiar with the talks.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin described Friday’s discussions as constructive as he left the U.S. Trade Representative’s office. Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, the top negotiator who led the talks in Washington, told reporters at his hotel that the talks went “fairly well.”

Yet several people familiar with the discussions said little progress was made during a working dinner on Thursday and in Friday morning talks. Liu didn’t come prepared to offer much more in the way of concessions, one of the people said.

Liu and his delegation were expected to leave Washington on Friday afternoon, according to a person familiar with their planning.

U.S. stocks fell for a fifth day on Friday, though they climbed from lows of the day after indications from American officials that the two sides will keep talking.

No Rush

Earlier Friday, Trump said there’s “no need to rush” a deal. “Talks with China continue in a very congenial manner -- there is absolutely no need to rush,” the U.S. president said on Twitter, before talks resumed. “In the meantime we will continue to negotiate with China in the hopes that they do not again try to redo deal!”

Amid the latest talks, the U.S. moved ahead with plans on Friday to increase the punitive tariff to 25% from 10% on 5,700 different product categories from China -- ranging from cooked vegetables to Christmas lights and highchairs for babies. China said it will be forced to retaliate, though the government didn’t immediately specify how.

The fresh wave of U.S. tariffs marked a sharp reversal from just last week, when U.S. officials expressed optimism that a pact was within reach. The escalation with China also signaled Trump’s willingness to risk more economic and political damage on his apparent belief that trade wars ultimately are winnable.

Meanwhile Chinese stock market jump higher

What trade war? China stocks jump after tariff hike

- Chinese shares stood defiant after their return from the lunch break, surging despite the U.S. imposing higher tariffs on Chinese goods.

- The U.S. raised tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods — from 10% to 25% — at 12:01 a.m. ET Friday.

- Beijing pledged to take countermeasures but did not provide specifics, Reuters reported.

Last edited:

Quickie

Colonel

We have lost 500 Billion Dollars a year, for many years, on Crazy Trade with China. NO MORE!

I guess POTUS always gets away with his crazy maths.

500B - 180B = 500B (USD).

And how did buying something and paying the money on your own free will become equated to "outright losing money"?

The sad thing is the majority of the masses probably believe him.

I guess POTUS always gets away with his crazy maths.

500B - 180B = 500B (USD).

And how did buying something and paying the money on your own free will become equated to "outright losing money"?

The sad thing is the majority of the masses probably believe him.

And you're not even factoring in the value of what was purchased with that money.

Quickie

Colonel

And you're not even factoring in the value of what was purchased with that money.

I did. "Buying something" already imply receiving something of value.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.