Chinese telecom tech is invading the physical world, but Europeans and industry have strategies to contain the threat.

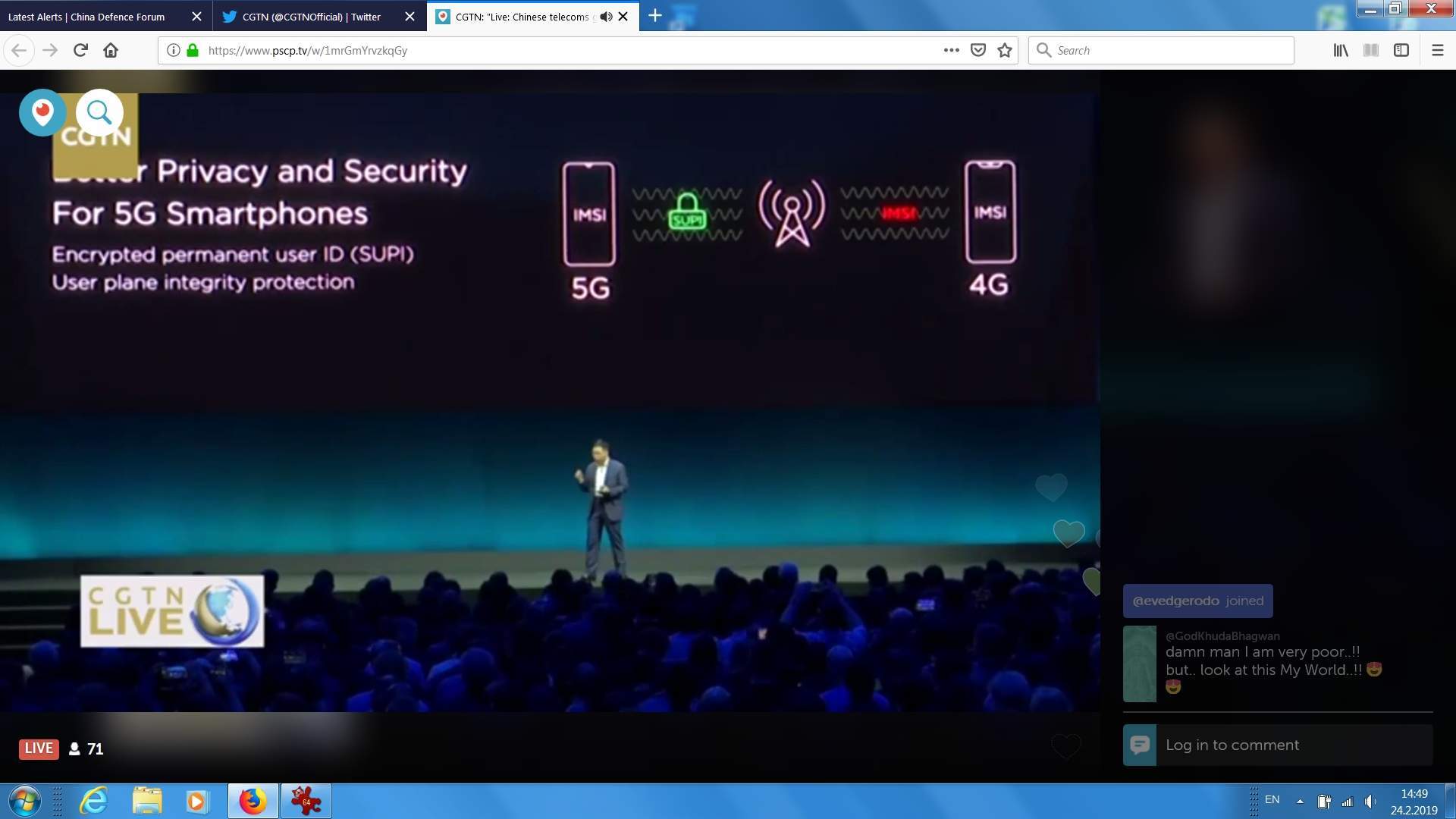

Much of the Western intelligence debate around Chinese high-speed 5G technology has focused on hardware and software. Once the hardware is already out in the wild — which most think is inevitable — the future of the fight is in managing risk. It’s doable, if not yet widely advertised, according to several experts speaking at a U.S. intelligence conference this week, by quarantining Chinese equipment and deploying smarter electromagnetic spectrum management tools to better handle threats.

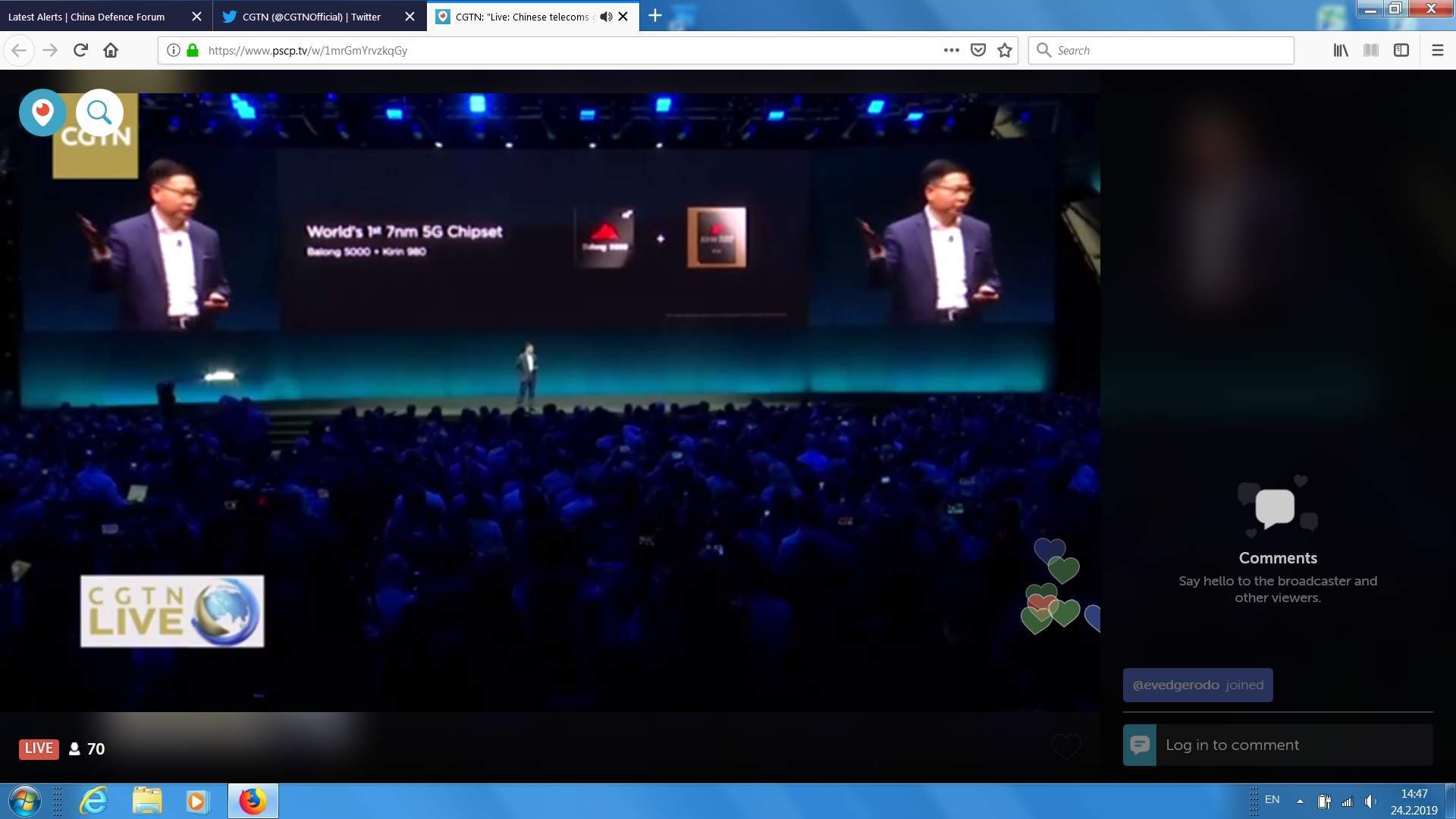

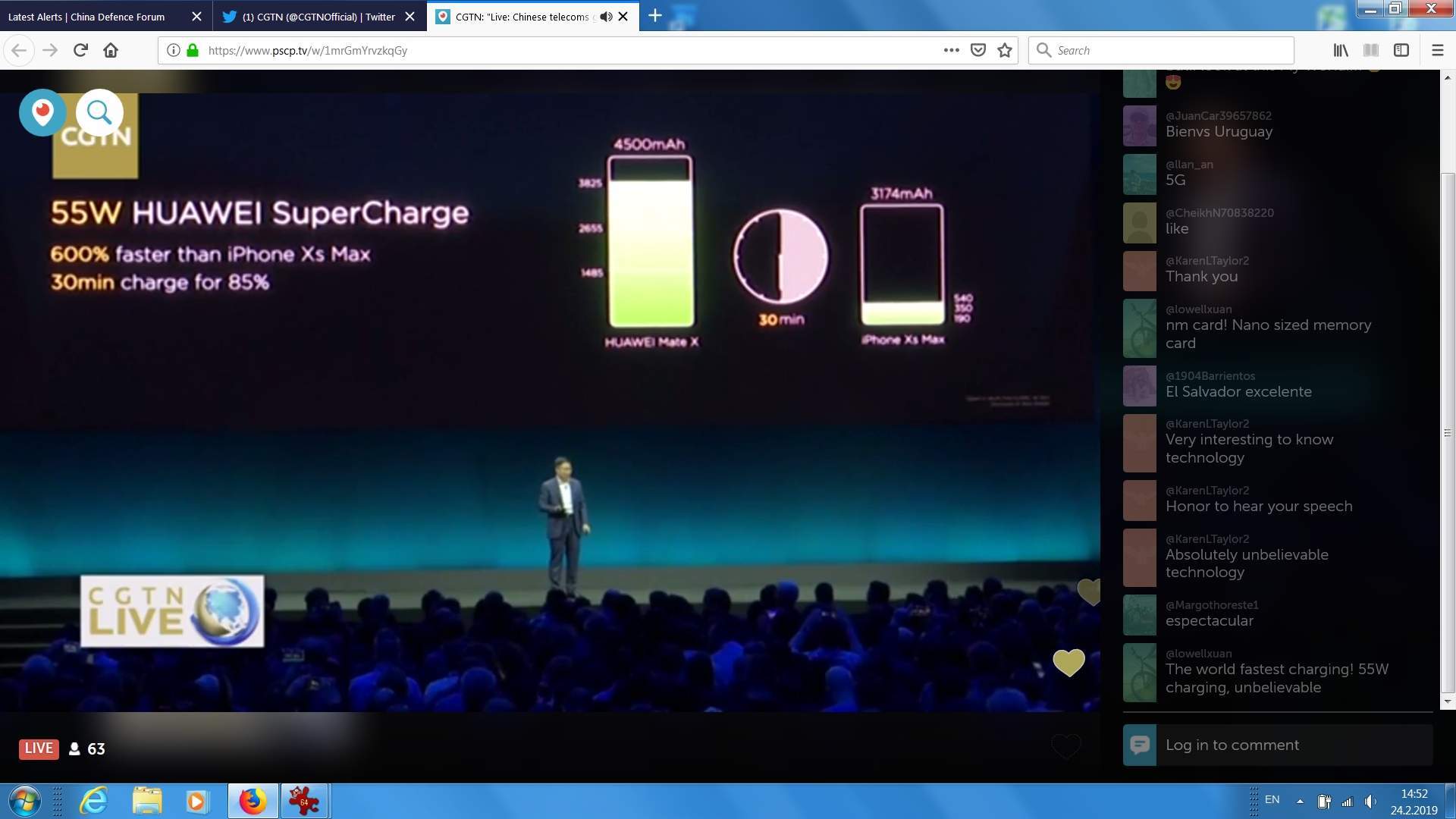

Bottom line: Huawei leads the world in the ability to rapidly produce cheap telecom hardware (as well as the underlying software.) Recent reports, including

, state it plainly. It’s one reason why European countries, including U.S. allies like Germany and the U.K., have been reluctant to ban tech from Huawei outright, even in the face of heavy U.S. pressure.

But — quietly — many European countries like the U.K. and France actually are banning Huawei’s 5G tech in part by effectively quarantining it away from vital parts of infrastructure, or military and intelligence activities, according to James Lewis, senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “They don’t let Huawei near their sensitive intelligence facilities, their sensitive military facilities,” said Lewis.

Some European countries are using architecture tricks to put Chinese tech on a short leash, Lewis said. For instance, a country might allow Huawei to play in the portion of the Radio Access Network where individual users connect to cell towers but not in what’s called

where those towers connect and communicate to one another via a shared central node. “The theory is…watch them in the core network,” he said.

If you haven’t heard about that, that’s in part by design. Europeans, says Lewis, are eager to appear more neutral than their U.S. counterparts. “They don’t go around announcing it.”

If the United States can convince other countries to take similar risk approaches, then they will succeed in limiting the reach of Chinese telecom, even if they don’t succeed in banning it.

One of the Department of Homeland Security’s top advisors on the matter would not say if DHS was advocating a similar approach to 5G for the U.S.

“The U.S. is having discussions internally about the approach we want to take,” said John Costello, senior advisor to the director of the Office of Strategy, Policy and Plans for the department’s newly established Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency.

Today’s discussion about Chinese hardware and software likely will look dated in a few years, as 5G apps require a lot of electromagnetic spectrum. In the United States, key areas of the so-called mid-band are ruled by the Navy and some satellite communications. The U.S. already is in the process of trying to figure out how the military and the public can share those areas of spectrum that are key to the development of future 5G apps and services.

Here’s where today’s military technology could play a role —

which is sometimes called cognitive electromagnetic warfare.

“Software-defined frequency selection is a key component of the technology,” for mitigating the risks posed by future, blended 5G networks, according to Leland Brown, technology development manager at Intel Federal.

Intel is working on “new technologies to not only have the devices change frequencies but understand where those threats exist and transfer connectivity,” Brown says, in order to identify and move away from potential threats, just as the computer aboard an F-35 fighter jet identifies, tracks, and attempts to trick jamming weapons within the spectrum. But there is only so much next-generation AI can do, he says.

“The more we connect things, the greater insecurity,” he says. That trend of connecting things shows no signs of stopping.