PSLV C-35 tracking Video:

From :

From :

Mega launchers for ISRO soon

Heavy lifting: With advanced semi-cryogenic engines, ISRO's ability to carry massive satellites will be tripled by 2020. File photo shows rocket lifting off from Sriharikota in 2014. — | AP

Apart from powering rockets to lift heavier satellites, it will also lower the cost per kilo.

An advanced Indian mega space launcher that can deliver ten-tonne and heavier communication satellites to space and using a semi-cryogenic engine is likely to to power ISRO’s launchers by around 2018.

That is the space agency’s next big space vehicle, having just achieved the GSLV for lifting 2,000-kg payloads. The agency is gearing up for first test flight of the GSLV Mark-III vehicle in December with a 4,000-kg payload.

Currently, the government has approved the development of the semi-cryogenic stage alone.

When fitted suitably into a launch vehicle, it will see India putting satellites of the class of 6,000 to 10,000 kilos — or with some variations, lift even 15,000-kg payloads — to geostationary transfer orbits at 36,000 km. The engine is expected to triple or quadruple ISRO's transportation ability.

Massive payloads

Pre-project work on what is called the SCE-200 began about four years back. "We plan to have an [semi-cryogenic] engine and stage capable of flight by the end of 2018 and try it on the GSLV-MkIII.

This would readily boost Mk-III's maximum lifting capability from 4,000 kg to 6,000 kg,” Dr K. Sivan, Director of Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre at Thiruvanthapuram, the lead centre for launch vehicle development, said.

Two years thereafter, around 2020, this will be enhanced to 15,000 kg by putting strap-ons in clusters — the stage where major European and U.S. launch providers already are.

The engine will use space-grade kerosene as fuel and liquid oxygen as oxidiser. The development is going on at the Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre and the ISRO Propulsion Complex at Mahendragiri in Tamil Nadu.

“The semi-cryogenic engine is getting fabricated. Testing of its pump and components has been going on. An engine testing facility is also getting set up at Mahendragiri,” Dr. Sivan said.

Apart from powering rockets to lift heavier satellites, it will also effectively lower the cost per kilogram to reach orbits, which is the goal of all space-faring nations, he said.

Liquid fuel

The high-power local capability is needed as Indian communication satellites move towards 5,000-plus kg and more from 2017. By then, ISRO plans to build and launch its heaviest 5,700-kg GSAT-11 spacecraft, although on a European Ariane rocket for a big fee. Its present rockets can lift only up to 2,000 kg to this orbit.

Dr. Sivan said, “The GSLV-MkIII that we plan to test in December has a core liquid fuel stage. When the semi-cryogenic engine gets ready, our plan is to replace the liquid stage with the SCE. We straightaway get six-tonne payload capability, two tonnes over what Mark III can give.”

Subsequently the plan is to have a modular vehicle (earlier called the unifield launch vehicle) which allows variations suited to different payloads; this being done with the PSLV with its three versions.

For example, Dr. Sivan said: “We can have a bigger semicryogenic stage with clustered engines, similar to what SpaceX did using nine Merlin engines. We can then get a payload of 15 tonnes in the GTO.”

I think you meant CZ-5.6 tonnes till 2018 and 10-15 tonnes (GTO) till 2020, comparable to Delta IVH or CZ-9.

India aims for 1st landing near moon’s south pole

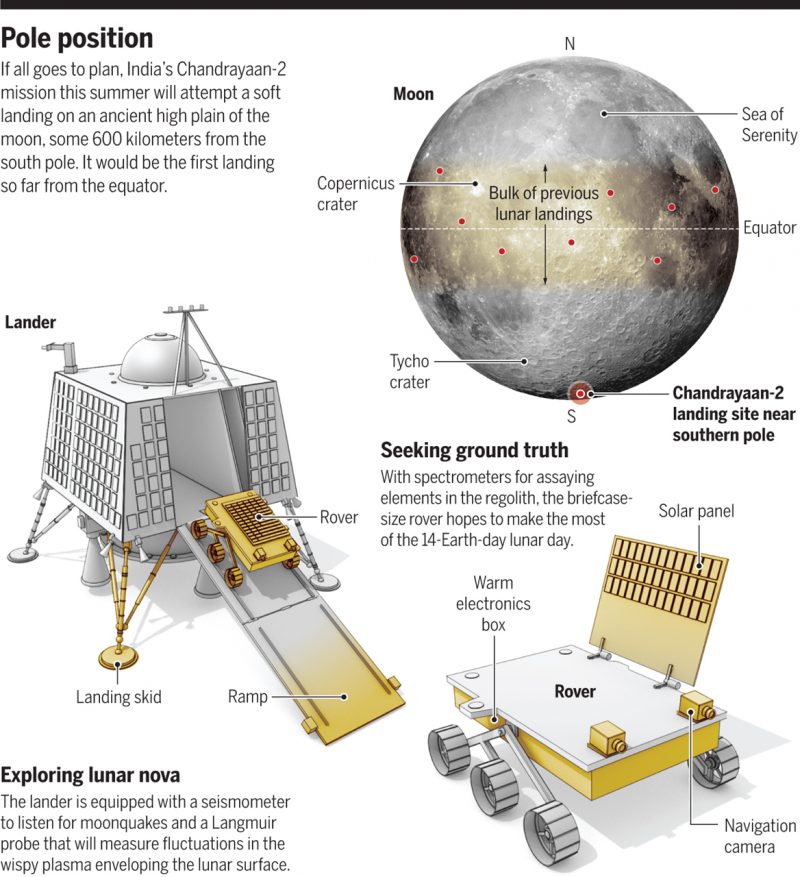

The moon’s south pole has never been explored from the ground, but India’s new Chandrayaan-2 mission will attempt a 1st-ever landing there, with a rover, this September.

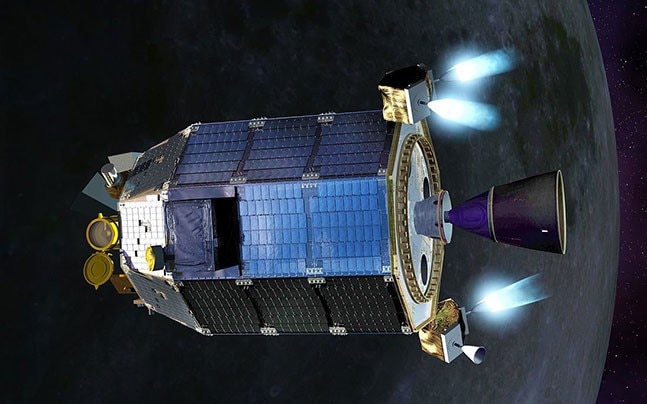

Artist’s concept of Chandrayaan-2 approaching the moon. If all goes well, a lander and rover will land near the lunar south pole in September of this year. Image via .

So far, only three countries have successfully landed on the moon – the United States, the former Soviet Union and China – but that might change soon, if all goes according to plan. India is preparing to launch its second lunar mission this summer, and this time the goal is to actually land on the surface, near the moon’s south pole. If successful, India would become the fourth nation to land on the moon and the spacecraft, , would be the first of any country to land in that region.

The Indian Space Research Organization () announced the plans via Twitter on May 1, 2019. As of now, the spacecraft is scheduled to launch sometime between July 9 and July 16, 2019, from the ISRO launch facility on , an island off India’s southeastern coast.

This new mission is more ambitious than any previous Indian mission to the moon, and will include an orbiter, . The landing itself won’t happen until September 6, 2019. As ISRO said in a statement:

All the modules are getting ready for Chandrayaan-2 launch during the window of July 9, to July 26, 2019, with an expected moon landing on September 6, 2019. The orbiter and lander modules will be interfaced mechanically and stacked together as an integrated module and accommodated inside the launch vehicle. The rover is housed inside the lander.

After landing, the rover is designed to operate for at least 14 days on the surface and drive 1,300 feet (396 meters). That may not sound like a lot compared to NASA’s rovers on Mars, which have been able to drive for many years and travel at least several miles (as well as the Apollo rovers on the moon), but it will be a big accomplishment for ISRO if it succeeds, since it will be their first-ever moon rover. As , ISRO chairman, The Times of India that, once Vikram lands on the lunar surface on September 6, the rover Pragyan will come out of the lander and roll out onto the lunar surface for about 300 to 400 meters (yards). It will spend 14 Earth-days on the moon, carrying out different scientific experiments. Altogether, he told The Times, there will be 13 payloads in the spacecraft: three payloads in rover Pragyan and the other 10 payloads in lander Vikram and orbiter.

Infographic detailing the lander and rover, as well as the landing site near the moon’s south pole. Image via .

The rover will use three scientific instruments including and a camera to analyze the content of the lunar surface and send data and images back to Earth through the orbiter.

The launch of this mission had originally been planned for April 2018, but it was delayed to changes in the spacecraft design. The four-legged Vikram lander (a qualification model) had also suffered a fracture in one of its landing legs during testing earlier this year, contributing to the delay.

The landing near the moon’s south pole will be uncharted territory, where no other spacecraft has landed before. Previous orbiter missions, including India’s , have found evidence for in craters in this region, in locations where there is permanent shadow. With no atmosphere to speak of, temperatures remain exceedingly cold in those areas – about minus 250 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 157 degrees Celsius) – even though they can be boiling hot in sunlit regions. Water ice would be a valuable resource for future crewed missions back to the moon.

This will be India’s second lunar mission. The first, Chandrayaan-1, orbited the moon but did not land. It launched in October 2008 and operated for 312 days, until August 2009. By all measures it was a great success, with the orbiter circling the moon about 3,400 times.

Artist’s concept of the Chandrayaan-2 rover on the moon, near the south pole. Image via .

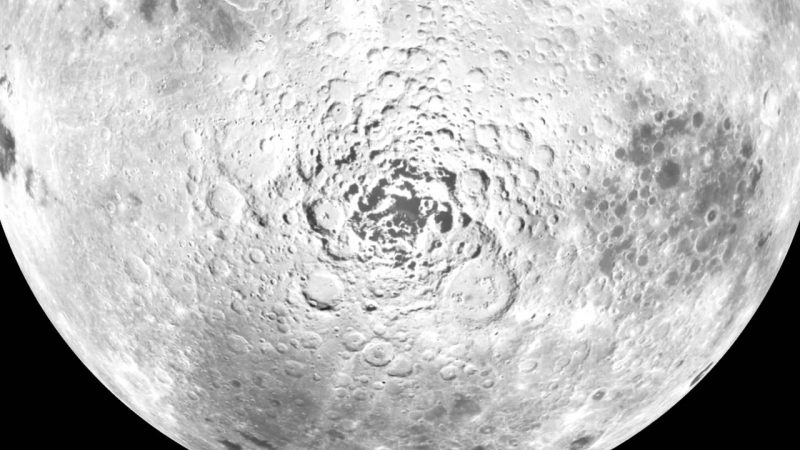

Still frame from animation showing the moon’s south pole as seen by NASA’s spacecraft in 1994. Image via .

On April 11, 2019, Israel’s spacecraft attempted – and the first landing of a commercial mission – but unfortunately it after a problem with the main engine in the last few moments before landing. A little earlier, however, on January 3, 2019, China’s spacecraft did on the far side of the moon, another first in lunar exploration.

Hopefully this next mission from India will fare better, as a follow-on to the successful first Chandrayaan-1 mission. If so, this will be the first view from the ground near the moon’s south pole that we will have ever had from any spacecraft. Although studied from orbit, this part of the moon is still virtually unexplored, so it is an exciting opportunity to learn more about our nearest neighbor in space.

Bottom line: If all goes according to plan, India will become the first nation to land a spacecraft near the moon’s south in September of this year.