Ultra

Junior Member

CNN is currently doing a piece on China's space program with rarely access to the Chinese "Space City" and interviews to the Chinese astronauts. Very interesting read!

China entered the space race late but it's now a force to be reckoned with. In a world exclusive, CNN sits down with three of the country's top astronauts and takes you inside its secretive space program.

Editorial: Katie Hunt, David McKenzie, Design: Nural Choudhury & Jason Kwok, Video: Ryan Smith, Development: Kevin Taverner, Nav Garcha

Inside Space City

If you stumbled into Space City, you probably wouldn't realize what it was.

The sprawling complex in the north west of Beijing shares the same nondescript character of government compounds throughout China.

But look closer. Guard posts over here; military sentries checking IDs over there.

This is no ordinary facility. Space City is home to the Chinese government's most ambitious and expensive mega-project ever. They've dubbed it "Project 921," the manned-space program.

And foreign journalists are almost never let in.

After more than a year of phone calls and faxes, here we are, inside the simulation room of the astronaut training center.

The astronauts stride into the room according to rank: Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang and Wang Yaping.

They're three of China's best-known astronauts and the crew of the 2013 Shenzhou-10 mission, China's longest manned spaceflight yet.

They're roughly the same height and build in their blue jumpsuits and black military boots.

That's no accident. Chinese astronauts are all People's Liberation Army pilots and officers, they have university degrees, they are Communist Party members. And they need to be around the same height and under a certain weight.

You don't need to be superhuman to be an astronaut, says Commander Nie.

"We are just ordinary people," he says, "But, yes, certain aspects make us more suitable to fly space missions."

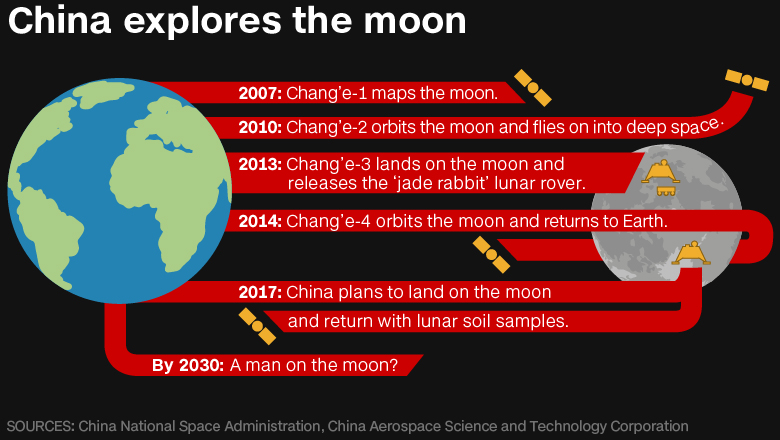

China's space program was first announced in the early 1970s, but the chaos of the Cultural Revolution stopped it in its tracks.

The program accelerated again in the early 1990s and space administrators picked two classes of astronauts in 1998 and 2010.

All of the crew of the 15-day Shenzhou-10 mission was passed over for missions at least once.

"When I wasn't selected for a mission, there was nothing I could do about it, so I just kept looking forward," says Zhang.

Zhang is the self-described joker of the group, able to lighten the mood during high-pressure situations. Still, he says he had to live through years of disappointments.

"I trained in this simulator for 15 years and I was in space for 15 days. So literally a day in space was a result of a year of training on the ground."

Perhaps the most famous of the group is Wang Yaping. She conducted a live space lecture for 60 million students across China during the mission.

"I remember, I watched the launch of the first Chinese astronaut into space with my fellow pilots," says Wang, who flew a transport plane for the PLA.

"I saw the fireball come out of the rocket and a thought just popped into my head: 'The first Chinese man just flew into space. When will the first female astronaut from China get there?'"

After years of training, you would think that it is all about the mission. But what happens when the space lectures and experiments are over?

"We really enjoyed the zero gravity situation in our spare time," says Wang. "It allowed us to practice tai chi upside down, it allowed us to float around like fish."

Race to the stars

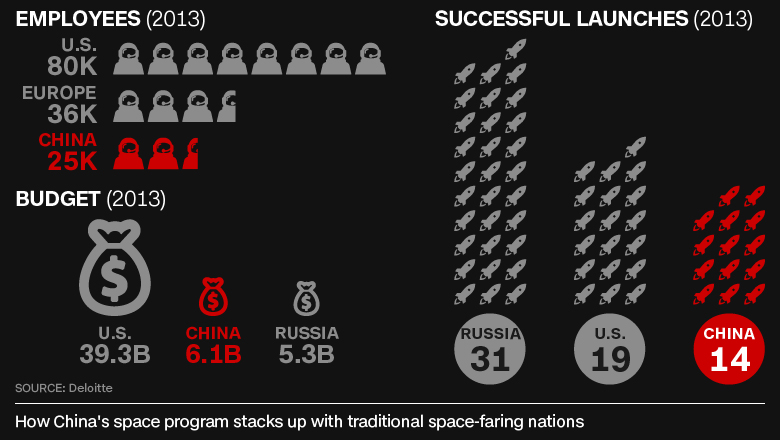

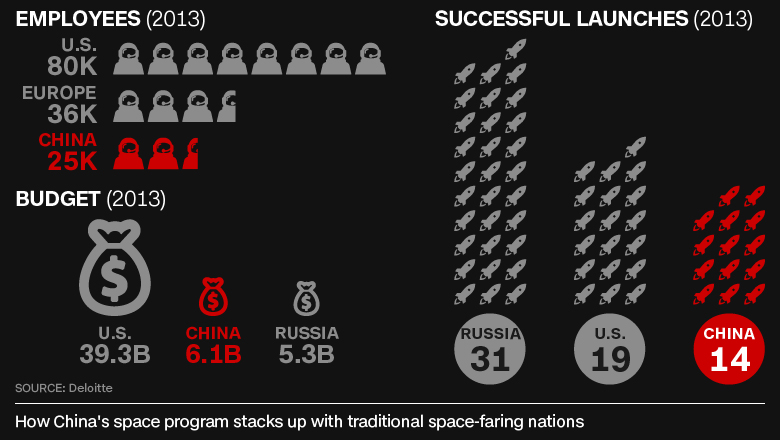

China's space program started late and is only now passing milestones the U.S. and Russia clocked years ago.

But, with the backing of the highest echelons of the Chinese Communist Party, it's going into space at a time when other world powers have scaled back on space exploration because of budget restraints or shifting priorities.

U.S. space technology is still "hands down the best in the world," says Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College, but she says the U.S. lacks the political will to fund an ambitious manned spaceflight program, China's is the pride of the nation.

"It would cost the US $140 billion for a true moon and Mars exploration mission but sticker shock would kill it instantly," she says.

"In terms of perception, America has already ceded its leadership in exploration to China."

Inside Space City, Commander Nie -- who leads the manned space mission -- is more diplomatic.

"The United States and Russia started their programs early. They are the pioneers," he says.

"Our space development is not because of some space competition or trying to overtake anyone."

But the modern race to the stars is not just about money, it's driven by technological advances and cooperation.

The International Space Station (ISS) houses a veritable United Nations in space with 15 countries contributing including the U.S., Russia and Japan.

But not China.

China's 21 astronauts are locked out of the ISS, largely because of pressure from U.S. legislators.

In 2011, Congress banned NASA from working bilaterally with anyone from the Chinese space program on national security concerns.

But a recent exhaustive report for the says China's improving space capability "has negative sum consequences for U.S. military security."

"China is viewed as a foe, it is viewed as a government that seeks to take our intellectual property, national secrets and treasure and thus Congress is not willing to partner with them," says CNN space and aviation analyst Miles O'Brien.

"I think it is ultimately a mistake."

The Chinese government says its space program is peaceful and already cooperates with other nations.

The crew of the Shenzhou-10 seem keen to work with NASA.

"As an astronaut, I have a very strong desire to fly space missions with astronauts from other countries. And I look forward to the opportunity go to the International Space Station," says Nie.

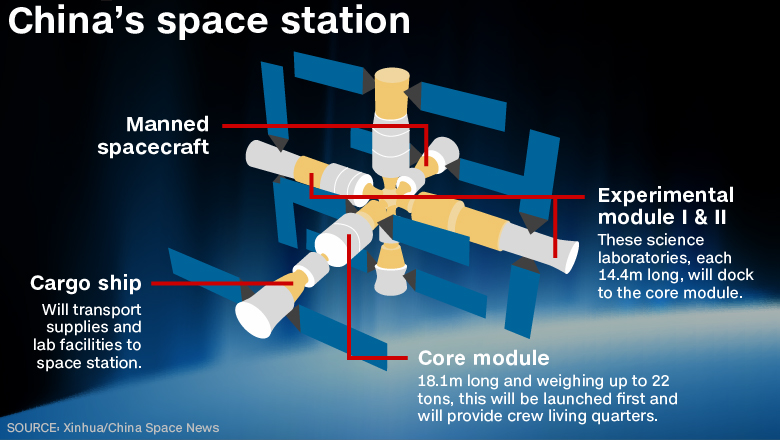

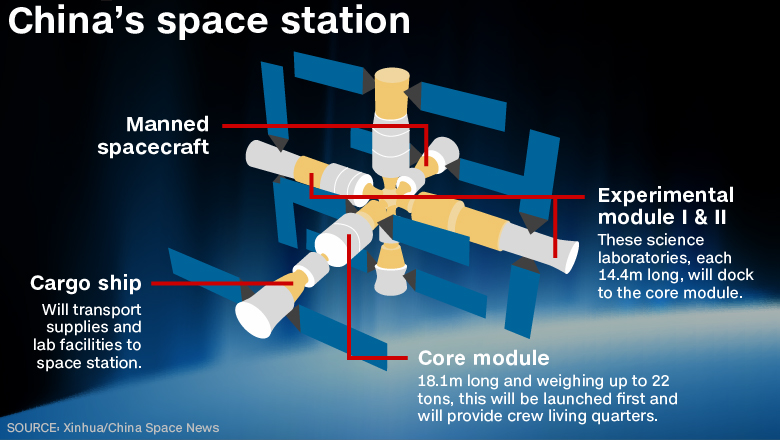

He says foreign astronauts are welcome to visit China's own space station once it is launched.

The Chinese expect to finish their space station by 2022 -- around the time the International Space Station runs out of funding, potentially leaving China as the only country with a permanent presence in space.

"They are on a slow steady campaign. I think in the end, tortoise versus hare style, they will probably win," says O'Brien.

China

The next space superpower?

The next space superpower?

China entered the space race late but it's now a force to be reckoned with. In a world exclusive, CNN sits down with three of the country's top astronauts and takes you inside its secretive space program.

Editorial: Katie Hunt, David McKenzie, Design: Nural Choudhury & Jason Kwok, Video: Ryan Smith, Development: Kevin Taverner, Nav Garcha

Inside Space City

If you stumbled into Space City, you probably wouldn't realize what it was.

The sprawling complex in the north west of Beijing shares the same nondescript character of government compounds throughout China.

But look closer. Guard posts over here; military sentries checking IDs over there.

This is no ordinary facility. Space City is home to the Chinese government's most ambitious and expensive mega-project ever. They've dubbed it "Project 921," the manned-space program.

And foreign journalists are almost never let in.

After more than a year of phone calls and faxes, here we are, inside the simulation room of the astronaut training center.

The astronauts stride into the room according to rank: Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang and Wang Yaping.

They're three of China's best-known astronauts and the crew of the 2013 Shenzhou-10 mission, China's longest manned spaceflight yet.

They're roughly the same height and build in their blue jumpsuits and black military boots.

That's no accident. Chinese astronauts are all People's Liberation Army pilots and officers, they have university degrees, they are Communist Party members. And they need to be around the same height and under a certain weight.

You don't need to be superhuman to be an astronaut, says Commander Nie.

"We are just ordinary people," he says, "But, yes, certain aspects make us more suitable to fly space missions."

China's space program was first announced in the early 1970s, but the chaos of the Cultural Revolution stopped it in its tracks.

The program accelerated again in the early 1990s and space administrators picked two classes of astronauts in 1998 and 2010.

All of the crew of the 15-day Shenzhou-10 mission was passed over for missions at least once.

"When I wasn't selected for a mission, there was nothing I could do about it, so I just kept looking forward," says Zhang.

Zhang is the self-described joker of the group, able to lighten the mood during high-pressure situations. Still, he says he had to live through years of disappointments.

"I trained in this simulator for 15 years and I was in space for 15 days. So literally a day in space was a result of a year of training on the ground."

Perhaps the most famous of the group is Wang Yaping. She conducted a live space lecture for 60 million students across China during the mission.

"I remember, I watched the launch of the first Chinese astronaut into space with my fellow pilots," says Wang, who flew a transport plane for the PLA.

"I saw the fireball come out of the rocket and a thought just popped into my head: 'The first Chinese man just flew into space. When will the first female astronaut from China get there?'"

After years of training, you would think that it is all about the mission. But what happens when the space lectures and experiments are over?

"We really enjoyed the zero gravity situation in our spare time," says Wang. "It allowed us to practice tai chi upside down, it allowed us to float around like fish."

Race to the stars

China's space program started late and is only now passing milestones the U.S. and Russia clocked years ago.

But, with the backing of the highest echelons of the Chinese Communist Party, it's going into space at a time when other world powers have scaled back on space exploration because of budget restraints or shifting priorities.

U.S. space technology is still "hands down the best in the world," says Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College, but she says the U.S. lacks the political will to fund an ambitious manned spaceflight program, China's is the pride of the nation.

"It would cost the US $140 billion for a true moon and Mars exploration mission but sticker shock would kill it instantly," she says.

"In terms of perception, America has already ceded its leadership in exploration to China."

Inside Space City, Commander Nie -- who leads the manned space mission -- is more diplomatic.

"The United States and Russia started their programs early. They are the pioneers," he says.

"Our space development is not because of some space competition or trying to overtake anyone."

But the modern race to the stars is not just about money, it's driven by technological advances and cooperation.

The International Space Station (ISS) houses a veritable United Nations in space with 15 countries contributing including the U.S., Russia and Japan.

But not China.

China's 21 astronauts are locked out of the ISS, largely because of pressure from U.S. legislators.

In 2011, Congress banned NASA from working bilaterally with anyone from the Chinese space program on national security concerns.

But a recent exhaustive report for the says China's improving space capability "has negative sum consequences for U.S. military security."

"China is viewed as a foe, it is viewed as a government that seeks to take our intellectual property, national secrets and treasure and thus Congress is not willing to partner with them," says CNN space and aviation analyst Miles O'Brien.

"I think it is ultimately a mistake."

The Chinese government says its space program is peaceful and already cooperates with other nations.

The crew of the Shenzhou-10 seem keen to work with NASA.

"As an astronaut, I have a very strong desire to fly space missions with astronauts from other countries. And I look forward to the opportunity go to the International Space Station," says Nie.

He says foreign astronauts are welcome to visit China's own space station once it is launched.

The Chinese expect to finish their space station by 2022 -- around the time the International Space Station runs out of funding, potentially leaving China as the only country with a permanent presence in space.

"They are on a slow steady campaign. I think in the end, tortoise versus hare style, they will probably win," says O'Brien.