So i was a bit overoptimistic, it seems. I guess i overestimated the inflation figure. Official GDP figure comes at 67,7 trillion yuan. If anyone is keen on dollar conversion, it should be 10,74 trillion for average exchange rate in 2015. 1.3% of GDP spent on military would give 139,7 billion dollars.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

China's Defense Spending Thread

- Thread starter antiterror13

- Start date

antiterror13

Brigadier

this time could be 1.5% of GDP for military

Lethe

Captain

Surely instead of projecting military spending using a flat % of GDP borrowed from prior years it would be more reasonable to assume military spending growth around 10% from the previous year's budget, i.e. the same growth as last year and most of the years before that?

It will be very interesting to see what the actual % increase turns out to be given that the past 12 months has seen not only a slowdown in the broader economy, but the ratcheting up on tensions in the South China Sea.

If the military budget follows the broader economy and thereby registers its slowest growth in decades, it will be perceived by the US and others as a strategic retreat, as an indication that China is not serious about challenging US hegemony in the Pacific and can be further dissuaded by increased pressure. Additionally, robust spending growth helps to smooth feathers ruffled by top-down military reforms.

For both reasons I do not expect Chinese military spending growth to dip below 10%/yr until at least 2020. As corollary, I expect China's military spending as percentage of GDP to slowly increase over time.

It will be very interesting to see what the actual % increase turns out to be given that the past 12 months has seen not only a slowdown in the broader economy, but the ratcheting up on tensions in the South China Sea.

If the military budget follows the broader economy and thereby registers its slowest growth in decades, it will be perceived by the US and others as a strategic retreat, as an indication that China is not serious about challenging US hegemony in the Pacific and can be further dissuaded by increased pressure. Additionally, robust spending growth helps to smooth feathers ruffled by top-down military reforms.

For both reasons I do not expect Chinese military spending growth to dip below 10%/yr until at least 2020. As corollary, I expect China's military spending as percentage of GDP to slowly increase over time.

Last edited:

In the last 11 years, defense spending was between 1,23 and 1,42 percent of gdp, with average value of 1,315%. While it's possible there is some cap on minimal growth, it's equally possible there is a cap dependant on GDP. One of smartest moves China did is when it lowered its military expenditure in 1980s from above 6% to where it is now and kept it there for decades, unburdening the economy. In stark contrast to what Soviet Union did or to what Russia is doing today. Chinese GDP growth is still quite strong and military budget is sure to raise even in total, inflation corrected terms. With savings from restructure and reducing the army, i don't see any pressure for keeping a strict 10% annual growth. We had a dip of "just" 7-8% increase in 2010, even though before and after that growth was above 10%. So there is precedent. Plus, in the last couple of years there is a visible trend of military budget growth being smaller and approaching 10%. Why wouldn't it be natural if it dipped below it a little? There is no magical boundary about it.

Nothing about chinese modernization/armament programme screams urgency. (unlike russian programme) So in the long run, it's much more prudent to stick with same spending as part of GDP then stick to some fixed growth sum, economy be damned.

Nothing about chinese modernization/armament programme screams urgency. (unlike russian programme) So in the long run, it's much more prudent to stick with same spending as part of GDP then stick to some fixed growth sum, economy be damned.

Hm, a question though. Why did China's NBS release GDP figure of 67.7 trillion yuan at comparable prices to last year? I thought the overall yearly GDP (not increase but total figure in country's respective currency) is usually expressed in actual average value of currency during the said period. So not at "comparable prices" but with prices adjusted for inflation instead. What happened there?

Lethe

Captain

In the last 11 years, defense spending was between 1,23 and 1,42 percent of gdp, with average value of 1,315%. While it's possible there is some cap on minimal growth, it's equally possible there is a cap dependant on GDP.

This is not possible because nobody budgets according to GDP. GDP is a secondary measure we use to analyse spending. Departments are not concerned about abstract GDP numbers, but rather whether they receive more funds than previous years, the same amount, or less. Annual growth (after inflation is taken into account) is much more important to the Chinese military than abstract GDP measures.

One of smartest moves China did is when it lowered its military expenditure in 1980s from above 6% to where it is now and kept it there for decades, unburdening the economy. In stark contrast to what Soviet Union did or to what Russia is doing today.

But this is not what happened. Central government did not go "ah, we will allow military spending to decline to X% GDP" rather the growth it budgeted for the military each year was of rate slower than growth in the broader economy, which had the effect of reducing military spending as measured by GDP. The same decline in spending as a proportion of GDP has happened in India and Pakistan in recent decades, yet neither has consciously allowed such a decline to occur.

With savings from restructure and reducing the army, i don't see any pressure for keeping a strict 10% annual growth. We had a dip of "just" 7-8% increase in 2010, even though before and after that growth was above 10%. So there is precedent. Plus, in the last couple of years there is a visible trend of military budget growth being smaller and approaching 10%. Why wouldn't it be natural if it dipped below it a little? There is no magical boundary about it.

10% is not a magical boundary, but nor is 2016 the same as 2010. Chinese capabilities are much greater today than they were even six years ago, and US and regional anxiety and pushback are much more of a factor. I do not argue that China should or should not allow military spending growth to slow to match the broader economy, but if China abandons decades of double-digit growth at the precise time that US begins to push back in SCS, it will be read that China is only committed to challenging US hegemony so long as doing so doesn't cost China anything, and therefore that applying further pressure (i.e. imposing costs) on China is a productive way to engage with the nation and halt its undesirable activities.

That this is how western powers would read such a move does not of itself mean mean that China should not do so if it judges it to be in its own interest, but it should certainly be aware of how it will be perceived throughout the region.

So in the long run, it's much more prudent to stick with same spending as part of GDP then stick to some fixed growth sum, economy be damned.

But you are the one suggesting sticking to some arbitrary fixed growth sum in the form of a static percentage of GDP. Military budget comes from the central government and is supplied by tax revenue (and borrowing), where tax revenue and dispensation is not an automatic reflection of the broader economy but reflects national priorities and philosophies and is in any case changing as the economy evolves. Simply put, as China becomes wealthier taxation has the potential (excluding corruption) to become more efficient, and for taxation as proportion of total economy to rise, and indeed this is already happening.

Last edited:

I think we agree GDP ratio figure is not something that's set but it can and does show dependance of military budget on the economy. It doesn't happen overnight, nor within a year, so i wouldn't expect the change to come right away with the announcement of next military budget figure in march. I'm sure various things are budgeted some years in advance and are thus more or less set. But i do expect we will see a continuing trend of smaller and smaller growth in the coming years. In march it may or may not go under 10% (politcs aside) but even if this and next year it does go 10% or over, in the long term 5-10 years i do expect it will be "cemented" under 10%, possibly closer to 8-9%.

How about that question of announcing GDP figure in comparable prices to last year? Why not count in inflation? Does such announcement come a bit later, inflation hasn't been estimated yet for the last quarter?

How about that question of announcing GDP figure in comparable prices to last year? Why not count in inflation? Does such announcement come a bit later, inflation hasn't been estimated yet for the last quarter?

plawolf

Lieutenant General

Actually, I think that as GDP growth slows, Chinese defence spending as a proportion of GDP will rise, not all.

As has already been pointed out, military budgets are usually set years in advanced in China, which is famous for its long term planning.

The other factor to consider is that for China, who is almost entirely self-sufficient in arms manufacturing, military spending is actually a form of government stimulus. This is especially apparent for the navy.

As commercial work has dried up, it is increasingly naval contracts that are keeping a lot of shipyards working, and their workers employed. As such, I think is no co-incidence that Chinese naval expansion has co-incided with global commercial shipping contraction (the SCS developments are also so influenced in my view, China has a lot of projects active and planned for the SCS, and I think a big part of that is to both take advantage of excess capacity and to give struggling yards and companies a lifeline).

In that extent, both the scope (number of shipyards involved) and speed of the naval shipbuilding makes a great deal more sense.

Using many different yards to build warships at the same time is less to do with any urgent need for ships, and more about spreading the benefits to keep as many yards working as possible. The very quick build times of ships is probably down to yards putting a lot more workers on the builds than necessary, since there is much less commercial work, its better to have them do something rather than get paid just sit around.

In that context, I think the PLA will benefit less from falling commodities prices than one would think. Again, as commercial demand falls, commodities producers are starting to feel the pinch. The PLA would be far more inclined to pass on that fall in demand to foreign exporters of raw commodities and cut imports of materials like steel, oil and other materials, but pay a higher than current market price to help domestic producers and suppliers rather than take full advantage of the price falls in commodities and materials.

This will be, in my view, a big reason to maintain original long term defence spending budgets rather than adjust them in light of current developments. The PLA will not reap the full benefits of recent price drops, since doing so will potentially squeeze key domestic suppliers and industries too much. That means that their expenses are unlikely to fall much, if at all, in spite of recent global price drops in key areas, and as such, you cannot cut their budget without making cut backs somewhere also.

As has already been pointed out, military budgets are usually set years in advanced in China, which is famous for its long term planning.

The other factor to consider is that for China, who is almost entirely self-sufficient in arms manufacturing, military spending is actually a form of government stimulus. This is especially apparent for the navy.

As commercial work has dried up, it is increasingly naval contracts that are keeping a lot of shipyards working, and their workers employed. As such, I think is no co-incidence that Chinese naval expansion has co-incided with global commercial shipping contraction (the SCS developments are also so influenced in my view, China has a lot of projects active and planned for the SCS, and I think a big part of that is to both take advantage of excess capacity and to give struggling yards and companies a lifeline).

In that extent, both the scope (number of shipyards involved) and speed of the naval shipbuilding makes a great deal more sense.

Using many different yards to build warships at the same time is less to do with any urgent need for ships, and more about spreading the benefits to keep as many yards working as possible. The very quick build times of ships is probably down to yards putting a lot more workers on the builds than necessary, since there is much less commercial work, its better to have them do something rather than get paid just sit around.

In that context, I think the PLA will benefit less from falling commodities prices than one would think. Again, as commercial demand falls, commodities producers are starting to feel the pinch. The PLA would be far more inclined to pass on that fall in demand to foreign exporters of raw commodities and cut imports of materials like steel, oil and other materials, but pay a higher than current market price to help domestic producers and suppliers rather than take full advantage of the price falls in commodities and materials.

This will be, in my view, a big reason to maintain original long term defence spending budgets rather than adjust them in light of current developments. The PLA will not reap the full benefits of recent price drops, since doing so will potentially squeeze key domestic suppliers and industries too much. That means that their expenses are unlikely to fall much, if at all, in spite of recent global price drops in key areas, and as such, you cannot cut their budget without making cut backs somewhere also.

Kanonen statt Butter oder kanonen und butter?

Xinhua:

BEIJING, Jan. 19 -- China's economy recorded the slowest annual expansion in a quarter of a century in 2015 as authorities signaled more supply-side structural reforms for long-term growth.

The economy grew 6.9 percent year on year in 2015, in line with the official target of around 7 percent for the year, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on Tuesday.

Growth in the fourth quarter (Q4) came in at 6.8 percent year on year, the lowest quarterly rate since the global financial crisis, the data showed.

Gross domestic product () was 67.67 trillion yuan (about 10.3 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2015, with the service sector accounting for 50.5 percent, the first time this has exceeded 50 percent.

China’s labour market

Shocks and absorbers

From The Economist 01/16/2016

THE crane that looms over Sainty Marine’s shipyard on the lower reaches of the Yangzi river had been motionless for weeks when a worker climbed it late last year. The struggling company had stopped getting orders and, rather than deal with the headache of laying off its employees, it simply stopped paying them. The man on the crane threatened to jump to get the attention of local officials, coming down only when they promised to help him. Other workers took a somewhat safer, though (in a country where strikes are illegal) no less provocative measure to demand their missing wages: they marched out and blockaded a nearby highway.

That Sainty Marine workers have resorted to such actions is perhaps not surprising. The global shipping industry is depressed, plagued by oversupply at a time when slowing trade means demand for new ships is shrinking. Chinese firms that rushed to expand are now gasping. Sainty Marine, which overextended itself by buying another shipbuilder, is veering towards bankruptcy. Withholding wages is a common tactic for Chinese companies in trouble; in Yizheng, the gritty town that is home to Sainty Marine’s shipyard, the local government has published statements admonishing employers for doing so.

Many workers at other hard-hit companies, especially in heavy industry, are facing similar frustrations. The China Labour Bulletin, a watchdog group based in Hong Kong, recorded 2,774 strikes and worker protests nationwide in 2015, double the 1,379 posted in 2014. Police arrested four labour activists last week in the southern province of Guangdong, China’s manufacturing heartland—a sign of the authorities’ unease over the growing protests.

Although the swooning stockmarket and falling currency have captured global attention in recent days, the effect of slowing growth on employment is a more sensitive problem for the government. The Communist Party has always treated markets and, by extension, investors with a certain disregard. Workers are different: the steady improvement in their living standards over the past three decades has helped to legitimise the party’s rule.

How worried should it be? The stresses have made only a small dent so far in overall employment figures, at least in the official telling. The jobless rate crept up to 5.2% at the end of September from 5.1% at the start of last year, according to the latest government survey of 31 big cities. Manufacturing firms are clearly cutting jobs: the employment index in the closely watched Caixin survey of the sector dipped to 47.3 in December—its 26th consecutive month below 50, the threshold marking a contraction. But for services, a bigger share of the economy than manufacturing, Caixin’s employment index hit 51.3 in December, above last year’s low of 50.1 in August. That points to an expansion.

However, the employment data are flattered by two uniquely Chinese shock-absorbers. First, the hukou system of household registration means that some 270m migrant workers who have gone to cities for jobs do not enjoy a permanent right to live in them, let alone collect unemployment insurance there. When they lose their jobs, they are expected to return to their original homes, often in the countryside, and do not count as unemployed. In 2008, at the height of the global financial crisis, tens of millions of migrants simply went back to rural areas, tilling fields or scrabbling for meagre pay in villages. There has been no similar exodus this time, but the countryside remains a safety valve that can help to absorb the unemployed.

The other buffer is one of the things hobbling the economy in the first place: state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Private firms are better run and more profitable, but SOEs, with their political backing, have far easier access to finance and dominate a series of restricted sectors, from energy to transport. These privileges carry with them political duties, including an obligation to help maintain social stability by refraining from laying off workers. With the army planning to cut some 300,000 positions as part of a modernisation plan, the government reminded SOEs last month that they are required to reserve 5% of vacancies for demobilised soldiers.

In a working paper last year, analysts at the International Monetary Fund noted signs of “increased labour hoarding in overcapacity sectors”, helping to suppress unemployment at the cost of weaker productivity. But even SOEs do not have infinite resources. Loss-making companies with little prospect of turning round their performance are starting to shed workers. Longmay Mining, the largest SOE in the northern province of Heilongjiang, said in September that it would cut up to 100,000 jobs, nearly half its workforce.

China’s economy should, in theory, be able to accommodate many of the unemployed. The working-age population peaked in 2012, so all else being equal, there is less competition for jobs. At the same time, the economy’s tilt towards the services sector, which is more labour-intensive than industry, generates jobs even as growth slows. Services probably accounted for more than half of China’s GDP last year for the first time in decades, and their share is growing: in nominal terms, service output grew by 11.6% year-on-year in the first nine months of 2015, whereas manufacturing grew by just 1.2%.

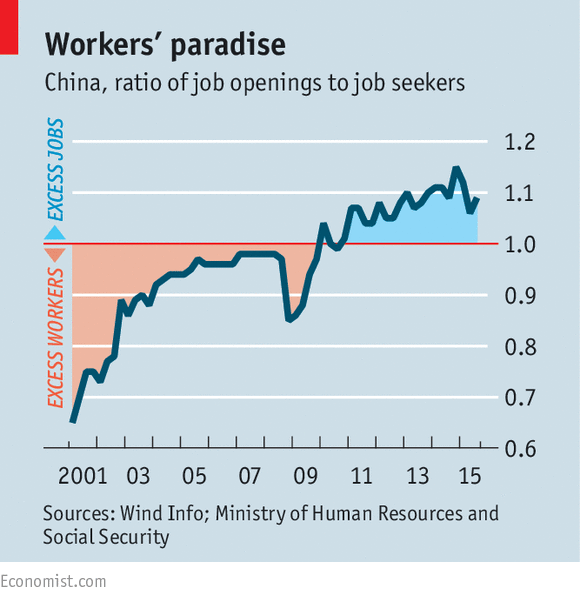

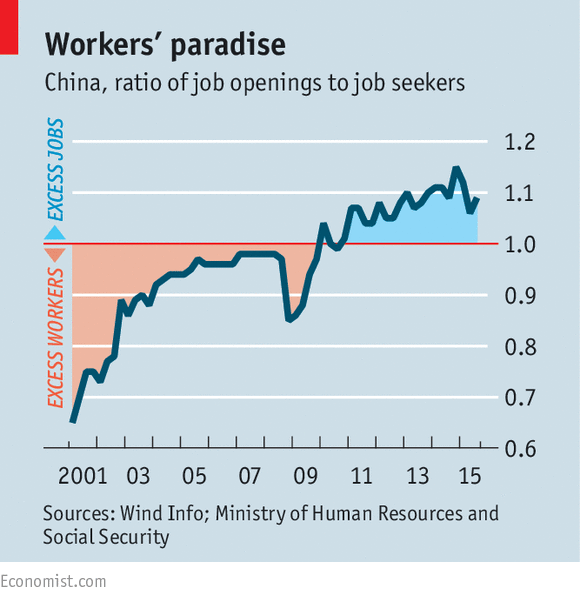

The central bank estimates that as long as the service sector’s share of GDP increased by one percentage point in 2015 (in fact, it did better), the economy could have slowed by nearly half a percentage point and yet still generated the same number of new jobs as it did in 2014. This helps to explain why employment centres around the country still report a shortage of workers: an average of 1.09 vacancies for every applicant (see chart). For those hoping to be hired by accounting firms or restaurants, opportunities are plentiful.

The problem for shipbuilders and coalminers is that many of the service jobs are destined for younger people with more education, and the jobs they can get, whether as janitors or cooks, often pay less well than their current work. The government has promised to provide retraining for those who lose jobs in industry, but that can only help so much. “Most of these guys can’t just go from making a living by their brawn to making a living by their brains,” says a recruiter at the human-resources centre in Yizheng.

For the employees of Sainty Marine, the question of what their next job might be is not the most pressing one. They have been showing up to work without getting paid. Mr Wang, 45, a welder, has a note signed by a manager stating that he is owed several months’ salary, money that he needs to pay back relatives who lent him cash to build a house. He joined the group blocking the highway, but that achieved nothing. He has tried to corner his bosses, but that also got him nowhere. Lately, he says, he has been looking at the crane, sizing it up for a climb.

Xinhua:

BEIJING, Jan. 19 -- China's economy recorded the slowest annual expansion in a quarter of a century in 2015 as authorities signaled more supply-side structural reforms for long-term growth.

The economy grew 6.9 percent year on year in 2015, in line with the official target of around 7 percent for the year, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on Tuesday.

Growth in the fourth quarter (Q4) came in at 6.8 percent year on year, the lowest quarterly rate since the global financial crisis, the data showed.

Gross domestic product () was 67.67 trillion yuan (about 10.3 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2015, with the service sector accounting for 50.5 percent, the first time this has exceeded 50 percent.

China’s labour market

Shocks and absorbers

From The Economist 01/16/2016

THE crane that looms over Sainty Marine’s shipyard on the lower reaches of the Yangzi river had been motionless for weeks when a worker climbed it late last year. The struggling company had stopped getting orders and, rather than deal with the headache of laying off its employees, it simply stopped paying them. The man on the crane threatened to jump to get the attention of local officials, coming down only when they promised to help him. Other workers took a somewhat safer, though (in a country where strikes are illegal) no less provocative measure to demand their missing wages: they marched out and blockaded a nearby highway.

That Sainty Marine workers have resorted to such actions is perhaps not surprising. The global shipping industry is depressed, plagued by oversupply at a time when slowing trade means demand for new ships is shrinking. Chinese firms that rushed to expand are now gasping. Sainty Marine, which overextended itself by buying another shipbuilder, is veering towards bankruptcy. Withholding wages is a common tactic for Chinese companies in trouble; in Yizheng, the gritty town that is home to Sainty Marine’s shipyard, the local government has published statements admonishing employers for doing so.

Many workers at other hard-hit companies, especially in heavy industry, are facing similar frustrations. The China Labour Bulletin, a watchdog group based in Hong Kong, recorded 2,774 strikes and worker protests nationwide in 2015, double the 1,379 posted in 2014. Police arrested four labour activists last week in the southern province of Guangdong, China’s manufacturing heartland—a sign of the authorities’ unease over the growing protests.

Although the swooning stockmarket and falling currency have captured global attention in recent days, the effect of slowing growth on employment is a more sensitive problem for the government. The Communist Party has always treated markets and, by extension, investors with a certain disregard. Workers are different: the steady improvement in their living standards over the past three decades has helped to legitimise the party’s rule.

How worried should it be? The stresses have made only a small dent so far in overall employment figures, at least in the official telling. The jobless rate crept up to 5.2% at the end of September from 5.1% at the start of last year, according to the latest government survey of 31 big cities. Manufacturing firms are clearly cutting jobs: the employment index in the closely watched Caixin survey of the sector dipped to 47.3 in December—its 26th consecutive month below 50, the threshold marking a contraction. But for services, a bigger share of the economy than manufacturing, Caixin’s employment index hit 51.3 in December, above last year’s low of 50.1 in August. That points to an expansion.

However, the employment data are flattered by two uniquely Chinese shock-absorbers. First, the hukou system of household registration means that some 270m migrant workers who have gone to cities for jobs do not enjoy a permanent right to live in them, let alone collect unemployment insurance there. When they lose their jobs, they are expected to return to their original homes, often in the countryside, and do not count as unemployed. In 2008, at the height of the global financial crisis, tens of millions of migrants simply went back to rural areas, tilling fields or scrabbling for meagre pay in villages. There has been no similar exodus this time, but the countryside remains a safety valve that can help to absorb the unemployed.

The other buffer is one of the things hobbling the economy in the first place: state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Private firms are better run and more profitable, but SOEs, with their political backing, have far easier access to finance and dominate a series of restricted sectors, from energy to transport. These privileges carry with them political duties, including an obligation to help maintain social stability by refraining from laying off workers. With the army planning to cut some 300,000 positions as part of a modernisation plan, the government reminded SOEs last month that they are required to reserve 5% of vacancies for demobilised soldiers.

In a working paper last year, analysts at the International Monetary Fund noted signs of “increased labour hoarding in overcapacity sectors”, helping to suppress unemployment at the cost of weaker productivity. But even SOEs do not have infinite resources. Loss-making companies with little prospect of turning round their performance are starting to shed workers. Longmay Mining, the largest SOE in the northern province of Heilongjiang, said in September that it would cut up to 100,000 jobs, nearly half its workforce.

China’s economy should, in theory, be able to accommodate many of the unemployed. The working-age population peaked in 2012, so all else being equal, there is less competition for jobs. At the same time, the economy’s tilt towards the services sector, which is more labour-intensive than industry, generates jobs even as growth slows. Services probably accounted for more than half of China’s GDP last year for the first time in decades, and their share is growing: in nominal terms, service output grew by 11.6% year-on-year in the first nine months of 2015, whereas manufacturing grew by just 1.2%.

The central bank estimates that as long as the service sector’s share of GDP increased by one percentage point in 2015 (in fact, it did better), the economy could have slowed by nearly half a percentage point and yet still generated the same number of new jobs as it did in 2014. This helps to explain why employment centres around the country still report a shortage of workers: an average of 1.09 vacancies for every applicant (see chart). For those hoping to be hired by accounting firms or restaurants, opportunities are plentiful.

The problem for shipbuilders and coalminers is that many of the service jobs are destined for younger people with more education, and the jobs they can get, whether as janitors or cooks, often pay less well than their current work. The government has promised to provide retraining for those who lose jobs in industry, but that can only help so much. “Most of these guys can’t just go from making a living by their brawn to making a living by their brains,” says a recruiter at the human-resources centre in Yizheng.

For the employees of Sainty Marine, the question of what their next job might be is not the most pressing one. They have been showing up to work without getting paid. Mr Wang, 45, a welder, has a note signed by a manager stating that he is owed several months’ salary, money that he needs to pay back relatives who lent him cash to build a house. He joined the group blocking the highway, but that achieved nothing. He has tried to corner his bosses, but that also got him nowhere. Lately, he says, he has been looking at the crane, sizing it up for a climb.

China's defense spending is not closely tied to annual GDP growth rate, but rather driven by the longer term defense modernization plan. Unless there is an economic hard landing or collapse, which is far from where we're and highly unlikely, I don't expect the annual defense spending growth rate changes all that much; they should hover around 10%.

This growth rate is necessary and sustainable.

As percentage of economy, China only spends about 1.3% GDP on defense, the lowest among any large nations, developed or otherwise. While the West likes to argue that China has hidden spending that may push the real defense spending towards 2% GDP (more a matter of accounting than any "hidden" agenda, similar to if one tallies the "real" US defense spending, it would be approaching $1 trillion). Even so, it's still among the lowest defense spending among major nations. On top of that, China's real GDP size is substantially underestimated (13% - 16%), primarily due to outdated global GDP framework China is currently using (1993 SNA). That system was revised to the 2008 SNA half a decade ago and countries have been making the conversion since, including Australia, Canada, the United States, European Union member states, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. (Source:

). This means that China's defense spending to GDP ratio is still lower. The Chinese central government has low debt (<25%) and low budget deficit (<3%). So there is no affordability issue both from an overall economy standpoint or the government budget standpoint.

It's also necessary and actually better for the economy if China gradually increases its defense spending over some time period, say, to 2.5% of GDP over 10 years, IMO.

As it stands now, Chinese economy is in a transition period, in need of restructuring (in terms of investment vs. consumption, manufacturing vs. service etc.) and upgrades (more high-tech, more innovative, less labor-intensive). Chinese military is also in the midst of transition, from quantity to quality and from low-tech to increasingly high-tech.

The areas that China needs to invest more and most are in the technology-intensive forces, i.e., air force, navy, space and electronics. They drive more indigenous R&D, which are needed by China and which tend to have more beneficial spin-off effects to the broader economy at this stage of Chinese economic development. It might not be very obvious to a lot of people, but the US defense spending during WWII and the post-war period were actually quite beneficial to the overall economy and technology developments (when it did not overly spend, which was the case during some time periods).

So I don't think there should be too much worries of negative impact on defense spending due to economy slowdown. China just needs to stay on the current steady course - it doesn't need a huge spike in defense spending which more likely cause waste and drag on economy nor does it need to slow down on spending. If there is no major event or crisis (like a Taiwan crisis) to disrupt the current trajectory, in fifteen years' time, China will have a modern and formidable defense force to safeguard its national interest.

This growth rate is necessary and sustainable.

As percentage of economy, China only spends about 1.3% GDP on defense, the lowest among any large nations, developed or otherwise. While the West likes to argue that China has hidden spending that may push the real defense spending towards 2% GDP (more a matter of accounting than any "hidden" agenda, similar to if one tallies the "real" US defense spending, it would be approaching $1 trillion). Even so, it's still among the lowest defense spending among major nations. On top of that, China's real GDP size is substantially underestimated (13% - 16%), primarily due to outdated global GDP framework China is currently using (1993 SNA). That system was revised to the 2008 SNA half a decade ago and countries have been making the conversion since, including Australia, Canada, the United States, European Union member states, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. (Source:

). This means that China's defense spending to GDP ratio is still lower. The Chinese central government has low debt (<25%) and low budget deficit (<3%). So there is no affordability issue both from an overall economy standpoint or the government budget standpoint.

It's also necessary and actually better for the economy if China gradually increases its defense spending over some time period, say, to 2.5% of GDP over 10 years, IMO.

As it stands now, Chinese economy is in a transition period, in need of restructuring (in terms of investment vs. consumption, manufacturing vs. service etc.) and upgrades (more high-tech, more innovative, less labor-intensive). Chinese military is also in the midst of transition, from quantity to quality and from low-tech to increasingly high-tech.

The areas that China needs to invest more and most are in the technology-intensive forces, i.e., air force, navy, space and electronics. They drive more indigenous R&D, which are needed by China and which tend to have more beneficial spin-off effects to the broader economy at this stage of Chinese economic development. It might not be very obvious to a lot of people, but the US defense spending during WWII and the post-war period were actually quite beneficial to the overall economy and technology developments (when it did not overly spend, which was the case during some time periods).

So I don't think there should be too much worries of negative impact on defense spending due to economy slowdown. China just needs to stay on the current steady course - it doesn't need a huge spike in defense spending which more likely cause waste and drag on economy nor does it need to slow down on spending. If there is no major event or crisis (like a Taiwan crisis) to disrupt the current trajectory, in fifteen years' time, China will have a modern and formidable defense force to safeguard its national interest.