April 24 (Bloomberg) -- China launched a satellite-killing

missile into space from a mobile platform that would make it

harder to destroy in a conflict, according to U.S. Air Force

Chief of Staff General Michael Moseley.

The Jan. 11 missile test revealed a capability that poses a

``significant risk to both civilian commercial systems and

military systems,'' Moseley said during a breakfast meeting with

reporters. ``The fact that it was mobile tells you a lot about

their ability to deploy and use it some where else,'' Moseley

said.

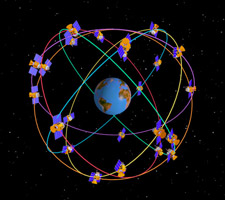

The missile test that destroyed an obsolete Chinese weather

satellite in low-earth orbit -- or up to 500 miles, where most

U.S. picture-taking spy satellites and commercial communications

satellites reside -- has drawn condemnation from several

nations, including Japan, Russia and the U.S. for introducing

weapons into space and adding to debris that can damage other

vehicles.

The test left a debris field of ``tens of thousands of

pieces,'' and ``China ought to be held accountable,'' said

Senator Bill Nelson, a Florida Democrat and a former astronaut,

at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing today.

Moseley's remarks today where the first by a U.S. military

official on the record that said China used a mobile system and

fired a missile that shot straight up at the satellite.

``The fact that it was a `direct ascent' that was `boom' --

that was a good piece of work,'' Moseley said after the

breakfast in commenting on the technical prowess involved in the

test.

Hard to Destroy

Moseley's disclosure was significant, said Loren Thompson,

a defense analyst who follows military space subjects for the

Lexington Institute in Arlington, Virginia.

Moseley's comments mean ``it would be real hard to destroy

these mobile systems at the beginning of a war,'' Thompson said.

``The Russians and U.S. at the end of the Cold War were moving

to place all their nuclear weapons on mobile platforms because

they knew they'd be difficult to destroy,'' he said.

The U.S. in conflicts, including the 1991 Persian Gulf War

and 1999 bombing campaign in Kosovo, had major difficulties

tracking mobile tracks, he said.

Moseley said the Chinese missile test was ``a strategically

dislocating event'' on par with the Soviet Union's launch of the

Sputnik satellite in 1957, spurring a ``space race'' with the

U.S.

The thousands of debris pieces created by the shooting of

the satellite include about 1,700 measuring three centimeters or

more that the U.S. Strategic Command is capable of tracking,

Nelson said.

Avoiding Debris

Major General William Shelton, an official for the

Strategic Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee on

April 19 that even pieces only of three-centimeters might cause

``catastrophic'' damage to satellites because of the speed at

which they move in space.

Nelson spokesman Barton Vaughan said in an e-mail statement

that the U.S. estimates ``tens of thousands of pieces larger

than one centimeter were created.'' U.S. satellites and the

International Space Station have been moved to avoid the debris,

he said.

The U.S. is especially vulnerable to interference with its

satellites because it is so dependent on them. Power, water

supply, gas and oil storage, banking and finance and government

services rely on satellite communications.

The military uses satellites for missile tracking,

intelligence gathering and secure voice communications.

Admiral Timothy Keating, head of the U.S. Pacific Command,

said he agreed with Nelson that holding China accountable for

any collateral damage caused by the debris it created ``is a

fair question'' that needs to be discussed.

Keating, in an interview after the hearing, said he was

going to talk with Chinese officials and reinforce the point

that the debris ``jeopardizes all manner of commercial and

military space vehicles.''