plawolf

Lieutenant General

I honestly don't know what some people want China to do.

There are Chinese all over the world, should Bejing send troops every time a Chinese national gets mugged abroad?

China has a strict non-interference policy, and it is abiding by that.

The KoKang might by ethnically Chinese, but they are not exactly helpless innocent victims of ethnic cleansing either.

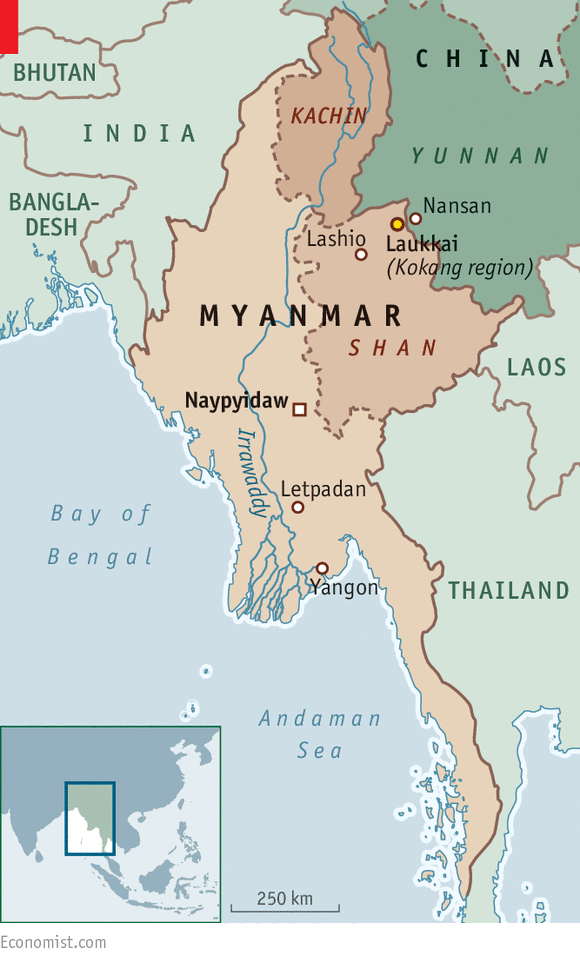

They are armed, organised and involved in a military conflict with the government of Myanmar. The current round of fighting started when they ambushed government troops. A lot of the funding for the KoKang militias come from drugs, gambling, prostitution and a lot of other highly illegal and amoral activities. Much of the drugs in Southern China comes from the 'golden triangle', to which the KoKang contribute.

Just because you are Chinese ethnically does not mean the Chinese government has any obligations to come bail you out when you get yourself into trouble, especially if its trouble of your own making. The vast majority of them are not even Chinese citizens.

The Myanmar bombing of Chinese soil is a serious issue that Beijing will not take lightly, but the plight of the KoKang are not China's problem or concern. Some people seems like they are itching for a fight sometimes.

It would serve Chinese interests far better if the KoKang disarmed, stopped all their illegal actives and just live peaceably with their neighbours.

There are Chinese all over the world, should Bejing send troops every time a Chinese national gets mugged abroad?

China has a strict non-interference policy, and it is abiding by that.

The KoKang might by ethnically Chinese, but they are not exactly helpless innocent victims of ethnic cleansing either.

They are armed, organised and involved in a military conflict with the government of Myanmar. The current round of fighting started when they ambushed government troops. A lot of the funding for the KoKang militias come from drugs, gambling, prostitution and a lot of other highly illegal and amoral activities. Much of the drugs in Southern China comes from the 'golden triangle', to which the KoKang contribute.

Just because you are Chinese ethnically does not mean the Chinese government has any obligations to come bail you out when you get yourself into trouble, especially if its trouble of your own making. The vast majority of them are not even Chinese citizens.

The Myanmar bombing of Chinese soil is a serious issue that Beijing will not take lightly, but the plight of the KoKang are not China's problem or concern. Some people seems like they are itching for a fight sometimes.

It would serve Chinese interests far better if the KoKang disarmed, stopped all their illegal actives and just live peaceably with their neighbours.