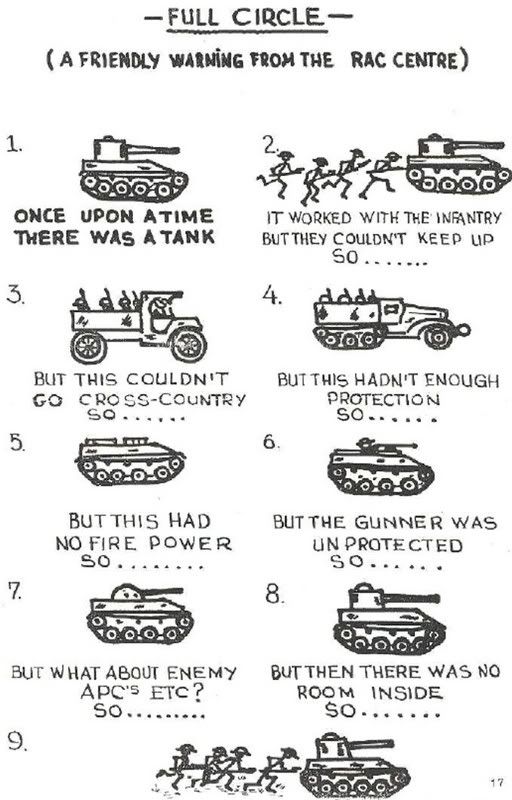

There is a lot more debate in recent years with the Iraq War and the Afghan War (and this is on top of the years of heavy debate about this subject in past decades) about the performance of APC's and IFV's, what they should be designed to do, and how to achieve such performance, including what compromises must be made to result in the best possible vehicle.

The original purpose of the APC was to get infantry as close as possible to their objectives while providing them with protection against small arms fire and mortar and artillery fragments. Lightly armoured half-tracks were used on both sides in WWII, and these provided light protection for an infantry squad/section while allowing it to use its weapons from inside the vehicle (in addition to the machine guns already mounted on the vehicle itself) to put suppressive fires on the enemy positions until the squad/section could dismount as close as possible to its objective. After the Normandy Landings in 1944, the half-track was found to be inadequately protected against German anti-tank weapons, so tank chassis were temporarily used to carry infantry into battle. None of the converted infantry-carrying tanks were lost, and the infantry suffered no losses while mounted either. However, the converted tank hulls carried no machine-guns, and no further development using tank chasis and hulls for APC occurred.

Since then, most APCs have been tracked to give them good mobility and have mounted machine-guns while carrying a squad/section as close as possible to their objectives. Other than providing overhead protection (which the WWII half-tracks did not), the APC is a relatively modest improvement over the half-track. In the last generation, the IFV has increasingly replaced the APC, usually with increased armour and firepower (typically light cannon, and sometime ATGM as well), but usually they can carry less than a full squad/section of 8-13 infantry. The original idea behind the IFV was that when the infantry did have to dismount, the smaller 6 or 7 man squad/section would constitute the assault element while the IFV itself would replace the support element (machine guns, etc.) of the squad/section.

This has not worked out well in practice for a few reasons. Firstly, the IFV is not always able to stay in contact (being in contact does not necessarily mean having to be in close company with the infantry, mind you) with its infantry, either due to the terrain or due to heavy enemy fire; thus the IFV may find itself necessarily separated from its infantry either because it can't get close enough to the objective to put suppressive fires on it, or out of self-preservation it must fight its own battle against enemy anti-tank weapons, etc. This deprives the infantry of its necessary base of fire.

Secondly, neither the IFV nor APC possess sufficient protection and mobility (contrary to official statements) to accompany tanks without unnecessarily risking either their own survival, or the infantry in the back of the vehicle. Even with applique and other advanced armours, IFVs cannot hope to survive hits by many anti-tank weapons; in Normandy, this problem was dealt with by converting tank hulls to APCs, and this was found to have worked. Additionally, due to their lighter weight (which is often used as an argument for greater mobility, but this has both pros and cons) IFVs cannot move as quickly or as easily over difficult ground as tanks can. The greater weight of the tanks actually (and counter-intuitively) "seats" them better, giving them not only better traction but most of all reduces the "bumps" that vehicles experience when travelling cross-country, thus reducing not only the fatugue of theose inside, but especially greatly reduces the number and potential of injuries to those inside.

A smoother ride afforded by a much heavier vehicle isn't just a luxury, it's a tactical necessity. Otherwise, IFVs either have to drive at break-necks speeds to keep up with the tanks (and despite what official literature says, IFVs have a hard time doing this) thus wearing out and injuring the infantry in back (bashed heads, impacted spines, weapons and kit bouncing around, people too) or the tanks are forced to slow down (or leave the IFVs behind - not a good idea to separate armour and infantry).

Thirdly, and this goes back in part to the first point, is the heavier armament carried by IFVs than APCs. At first, this sounds good, but when one remembers that doing so takes up a lot more internal space inside the vehicle (as a cannon requires a turret basket or "cage" with the commander and gunner seated inside along with all the ammo, fire control equipment, etc., thus taking up space that otherwise could be used for 3-4 more infantry and their kit).

The light cannon that most IFV have cannot penetrate the frontal armour of most newer generations MBTs, though they may be able to penetrate the turret ring (as the 25mm on a LAV-25 id on an Iraqi T-55 in 1991, et al) as well as the rear and possibly side armour. But getting the opportunity to do so is rare (and very risky). Any MBT needless to say, can destroy any IFV from any angle.

The only practical defence IFVs have against MBTs are ATGMs, but usually the IFV has to stop to aim and fire, and then remain in situ to guide the missile to its target, exposing it to enemy fire. The tank can fire on the move, and fire-and-forget and get itself out of the way; the IFV cannot.

To add to this, wheeled APCs/IFVs have become very popular lately, and their advocates assert their ease of maintenance and much reduced logistical needs compared to tracked vehicles, their lighter weight (and apparent ease of deployability), not to mention that their overall lighter weight compared to tracked IFVs (but still only equal to that of tracked APCs) allows them to travel over softer ground in some cases, not to mention travel much faster and farther on roads, and without need for tank transporters to avoid wear-and-tear (and breakdown).

But wheeled APCs/IFVs are not without their problems. As mentioned, they are not lighter than many tracked APCs, and tracked vehicles can still move cross-country better than wheeled vehicles under most conditions. Wheeled vehicles suffer from greater hull and suspension stress than tracked vehicles, leadin to their partial replacement in places like Afghanistan by tracked APCs asthe wheeled APCs hulls crack after sustained off-road use. And of course, light weight affects the well-being of the troops in back, as not only do wheeled APCs do not carry as much protection as tracked IFVs, but the troops in back are much more subject to being knocked about inside the vehicle as they travel cross-country. I still remember travelling in the back of a LAV-25, and although it is a great improvement comfort-wise over the original LAV, we were still being thrown around inside when the LAV reached higher speed, and it was quite a struggle (and tiring) to hang on to our weapons and kit while we were being bounced around all over the place.

There are a lot of things to be considered, and compromises to be carefully weighed when deciding on the form of an Infantry fighting Vehicle.

1. The role of an IFV must be to get its infantry as close as practically possible to their objective (in offensive operations) or to get them to or from their positions as quickly as possible (defensive operations). This requires that the IFV have protection similar to or approaching that of an MBT. It also requires that the infantry, if possible, be able to have roof panels that open up (ideally in much the same manner as tank hatches do, with an ability to open up part-way to provide overhead cover against small arms and fragments while the infantry fight from inside the vehicle on their way to the objective). A turret-mounted weapon on such an IFV may, or may not, interfere with this, both from the revolving turret itself as it traverses and from the guns/missiles it carries and the blast effects and gases released from their firing).

2. The IFV must carry a full-sized infantry squad/section, not a reduced one, so that the infantry can still perform fire-and-movement if the IFV for whatever reason is unable to provide fire support.

3. The IFV must be heavy enough to be able to cross country and obstacles at the same rate as MBTs, so that the IFVs do not lack too far behind or the tanks are forced to slow down to let the IFVs catch up, or risk separating armour and infantry with potentially devastating results in the event of contact with the enemy (no need to do part of the enemy's work for him).

4. The IFV's weaponry (and associated ammo and fire control equipment, etc.) must be a secondary consideration compared to the need for getting a full-sized infantry squad/section to and from battle with the same or nearly the same protection as an MBT while being able to keep up with the tanks cross-country without unecessarily battering and injuring the infantry inside. As such, cannon, whether light automatic or heavier close-support howitzers may not necessarily be the best way to go on an IFV, especially given two considerations: 1. Neither weapon can reasonably be expected to penetrate the frontal armour of an MBT or even an IFV with MBT-approximate level protection, let alone at the range at which a tank main gun can; and 2. The turret cage, ammunition stowage, fire control equipment, power systems, tools, etc,. for these weapons will necessarily take up a lot of space, and as such priotity for space must be given to the needs of a full infantry squad/section first, then other considerations, such the armament secondarily. Given that many IFVs use ATGMs to counter tanks, this space available for armament will be very limited indeed.

5. The IFV must (obviously) have sufficient armament. The IFV normally operates 100 metres or so behind the tanks (as the tanks engage enemy tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons with their main guns) in offensive operations, and will normally remain behind dug-in infantry positions during defensive operations. It must have a rapid-rate, direct-fire capability against any target short of a tank (or any vehicle with MBT-approximate protection), and if possible, a fire-and-forget ATGM to deal with tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons that get past friendly tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons, as well as enemy light armour, field fortifications, and even helicopters, etc.

For the first, the IFV requires at least a Heavy Machine Gun, possibly an automatic cannon, but the latter takes up a great deal of space, and as it cannot take out newer generation enemy MBTs (an ATGM is require dto do so), the range and firepower advantages over an HMG are in considerable part nulliied, especially when the additional space for it reduces the amount of space for infantry. The ATGM, as mentioned, is necessary to deal with anything the HMG can't, but the ATGM must be fire-and-forget so that the IFV does not have to remain exposed after firing to guide the missile to its target. Space for the HMG and the ATGM launcher and the ammo for each, along with fire control equipment will be reduced if a surveillance and fire control system along the lines of the UK version of the US Javelin ATGM are used instead of the systems used for M-2 Bradley and the like, etc. In fact, in some ways it may even be a bit of an improvement. Smoke grenade launchers are a given on an armoured vehicle, for obvious reasons.

The HMG ideally would be mounted inside a small turret allowing the Commander (or Gunner, if a 3-man crew is necessary) to fire and reload the gun inside (if the HMG is gas-operated, and not recoil-operated, modifications to the HMG will be necessary to prevent gas fumes from entering the turret). A hatch in the roof of the hull would be best for reloading the ATGM launcher (somewhat as M-2 Bradley also uses, although a Javelin or Spike-type missile would be much lighter than a TOW!). A minumum of 1,000 rounds of HMG ammo would be necessary (preferably much, much more, along with 2 or 3 spare barrels, etc.), but probably no more than a dozen ATGMs (of Javelin or Spike size, not TOW, HOT, etc. size,) could be carried onboard (including those already loaded in the launcher) or even be necessary (after all the tanks and the heavy-anti-tank weapons are the principle anti-armour weapons, not the IFV). This is also important to remember when considering that the maximum range of fire-and-forget ATGM in the class of Javelin and Spike is 2,500 m. Heavier weapons with greater range are available, but they are not fire-and-forget (with maybe one or two exceptions) and these are the very weapons that are best employed by heavy-anti-tank units.

Two additional considerations for the main armament of the IFV. First, if possible the HMG should be fully stabilized in both axes for accurate fire on the move and at helicopters, and the ATGM ideally should be able to be fired on the move; these are important, especially in offensive operations. Second, the HMG and the ATGM should be able to be removed and mounted on tripods for anti-armour work from dug-in position during defensive operations. The HMG and ATGM are partially wasted in their usage during defensive operations when they remain on the IFV. They are much more effective when firing into the enemy flanks from dug-in positions. The HMGs would efficiently despatch the enemy light armour while the ATGMs would engage the tanks. The idea here is that, unless the enemy acheives a decisive break-through (in which case the HMGs and ATGMs must be quickly re-mounted on the IFVs), the infantry should fix the attacking enemy forces while the armour with their tanks deliver a counter-attack to destroy the attacking enemy force.

This is by no means an exhaustive analysis of the requirements for an IFV. Arguably, however, it can give one some idea of the tactical issues and practical difficulties involved in conceptualizing a proper Infantry Fighting Vehicle.

The original purpose of the APC was to get infantry as close as possible to their objectives while providing them with protection against small arms fire and mortar and artillery fragments. Lightly armoured half-tracks were used on both sides in WWII, and these provided light protection for an infantry squad/section while allowing it to use its weapons from inside the vehicle (in addition to the machine guns already mounted on the vehicle itself) to put suppressive fires on the enemy positions until the squad/section could dismount as close as possible to its objective. After the Normandy Landings in 1944, the half-track was found to be inadequately protected against German anti-tank weapons, so tank chassis were temporarily used to carry infantry into battle. None of the converted infantry-carrying tanks were lost, and the infantry suffered no losses while mounted either. However, the converted tank hulls carried no machine-guns, and no further development using tank chasis and hulls for APC occurred.

Since then, most APCs have been tracked to give them good mobility and have mounted machine-guns while carrying a squad/section as close as possible to their objectives. Other than providing overhead protection (which the WWII half-tracks did not), the APC is a relatively modest improvement over the half-track. In the last generation, the IFV has increasingly replaced the APC, usually with increased armour and firepower (typically light cannon, and sometime ATGM as well), but usually they can carry less than a full squad/section of 8-13 infantry. The original idea behind the IFV was that when the infantry did have to dismount, the smaller 6 or 7 man squad/section would constitute the assault element while the IFV itself would replace the support element (machine guns, etc.) of the squad/section.

This has not worked out well in practice for a few reasons. Firstly, the IFV is not always able to stay in contact (being in contact does not necessarily mean having to be in close company with the infantry, mind you) with its infantry, either due to the terrain or due to heavy enemy fire; thus the IFV may find itself necessarily separated from its infantry either because it can't get close enough to the objective to put suppressive fires on it, or out of self-preservation it must fight its own battle against enemy anti-tank weapons, etc. This deprives the infantry of its necessary base of fire.

Secondly, neither the IFV nor APC possess sufficient protection and mobility (contrary to official statements) to accompany tanks without unnecessarily risking either their own survival, or the infantry in the back of the vehicle. Even with applique and other advanced armours, IFVs cannot hope to survive hits by many anti-tank weapons; in Normandy, this problem was dealt with by converting tank hulls to APCs, and this was found to have worked. Additionally, due to their lighter weight (which is often used as an argument for greater mobility, but this has both pros and cons) IFVs cannot move as quickly or as easily over difficult ground as tanks can. The greater weight of the tanks actually (and counter-intuitively) "seats" them better, giving them not only better traction but most of all reduces the "bumps" that vehicles experience when travelling cross-country, thus reducing not only the fatugue of theose inside, but especially greatly reduces the number and potential of injuries to those inside.

A smoother ride afforded by a much heavier vehicle isn't just a luxury, it's a tactical necessity. Otherwise, IFVs either have to drive at break-necks speeds to keep up with the tanks (and despite what official literature says, IFVs have a hard time doing this) thus wearing out and injuring the infantry in back (bashed heads, impacted spines, weapons and kit bouncing around, people too) or the tanks are forced to slow down (or leave the IFVs behind - not a good idea to separate armour and infantry).

Thirdly, and this goes back in part to the first point, is the heavier armament carried by IFVs than APCs. At first, this sounds good, but when one remembers that doing so takes up a lot more internal space inside the vehicle (as a cannon requires a turret basket or "cage" with the commander and gunner seated inside along with all the ammo, fire control equipment, etc., thus taking up space that otherwise could be used for 3-4 more infantry and their kit).

The light cannon that most IFV have cannot penetrate the frontal armour of most newer generations MBTs, though they may be able to penetrate the turret ring (as the 25mm on a LAV-25 id on an Iraqi T-55 in 1991, et al) as well as the rear and possibly side armour. But getting the opportunity to do so is rare (and very risky). Any MBT needless to say, can destroy any IFV from any angle.

The only practical defence IFVs have against MBTs are ATGMs, but usually the IFV has to stop to aim and fire, and then remain in situ to guide the missile to its target, exposing it to enemy fire. The tank can fire on the move, and fire-and-forget and get itself out of the way; the IFV cannot.

To add to this, wheeled APCs/IFVs have become very popular lately, and their advocates assert their ease of maintenance and much reduced logistical needs compared to tracked vehicles, their lighter weight (and apparent ease of deployability), not to mention that their overall lighter weight compared to tracked IFVs (but still only equal to that of tracked APCs) allows them to travel over softer ground in some cases, not to mention travel much faster and farther on roads, and without need for tank transporters to avoid wear-and-tear (and breakdown).

But wheeled APCs/IFVs are not without their problems. As mentioned, they are not lighter than many tracked APCs, and tracked vehicles can still move cross-country better than wheeled vehicles under most conditions. Wheeled vehicles suffer from greater hull and suspension stress than tracked vehicles, leadin to their partial replacement in places like Afghanistan by tracked APCs asthe wheeled APCs hulls crack after sustained off-road use. And of course, light weight affects the well-being of the troops in back, as not only do wheeled APCs do not carry as much protection as tracked IFVs, but the troops in back are much more subject to being knocked about inside the vehicle as they travel cross-country. I still remember travelling in the back of a LAV-25, and although it is a great improvement comfort-wise over the original LAV, we were still being thrown around inside when the LAV reached higher speed, and it was quite a struggle (and tiring) to hang on to our weapons and kit while we were being bounced around all over the place.

There are a lot of things to be considered, and compromises to be carefully weighed when deciding on the form of an Infantry fighting Vehicle.

1. The role of an IFV must be to get its infantry as close as practically possible to their objective (in offensive operations) or to get them to or from their positions as quickly as possible (defensive operations). This requires that the IFV have protection similar to or approaching that of an MBT. It also requires that the infantry, if possible, be able to have roof panels that open up (ideally in much the same manner as tank hatches do, with an ability to open up part-way to provide overhead cover against small arms and fragments while the infantry fight from inside the vehicle on their way to the objective). A turret-mounted weapon on such an IFV may, or may not, interfere with this, both from the revolving turret itself as it traverses and from the guns/missiles it carries and the blast effects and gases released from their firing).

2. The IFV must carry a full-sized infantry squad/section, not a reduced one, so that the infantry can still perform fire-and-movement if the IFV for whatever reason is unable to provide fire support.

3. The IFV must be heavy enough to be able to cross country and obstacles at the same rate as MBTs, so that the IFVs do not lack too far behind or the tanks are forced to slow down to let the IFVs catch up, or risk separating armour and infantry with potentially devastating results in the event of contact with the enemy (no need to do part of the enemy's work for him).

4. The IFV's weaponry (and associated ammo and fire control equipment, etc.) must be a secondary consideration compared to the need for getting a full-sized infantry squad/section to and from battle with the same or nearly the same protection as an MBT while being able to keep up with the tanks cross-country without unecessarily battering and injuring the infantry inside. As such, cannon, whether light automatic or heavier close-support howitzers may not necessarily be the best way to go on an IFV, especially given two considerations: 1. Neither weapon can reasonably be expected to penetrate the frontal armour of an MBT or even an IFV with MBT-approximate level protection, let alone at the range at which a tank main gun can; and 2. The turret cage, ammunition stowage, fire control equipment, power systems, tools, etc,. for these weapons will necessarily take up a lot of space, and as such priotity for space must be given to the needs of a full infantry squad/section first, then other considerations, such the armament secondarily. Given that many IFVs use ATGMs to counter tanks, this space available for armament will be very limited indeed.

5. The IFV must (obviously) have sufficient armament. The IFV normally operates 100 metres or so behind the tanks (as the tanks engage enemy tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons with their main guns) in offensive operations, and will normally remain behind dug-in infantry positions during defensive operations. It must have a rapid-rate, direct-fire capability against any target short of a tank (or any vehicle with MBT-approximate protection), and if possible, a fire-and-forget ATGM to deal with tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons that get past friendly tanks and heavy anti-tank weapons, as well as enemy light armour, field fortifications, and even helicopters, etc.

For the first, the IFV requires at least a Heavy Machine Gun, possibly an automatic cannon, but the latter takes up a great deal of space, and as it cannot take out newer generation enemy MBTs (an ATGM is require dto do so), the range and firepower advantages over an HMG are in considerable part nulliied, especially when the additional space for it reduces the amount of space for infantry. The ATGM, as mentioned, is necessary to deal with anything the HMG can't, but the ATGM must be fire-and-forget so that the IFV does not have to remain exposed after firing to guide the missile to its target. Space for the HMG and the ATGM launcher and the ammo for each, along with fire control equipment will be reduced if a surveillance and fire control system along the lines of the UK version of the US Javelin ATGM are used instead of the systems used for M-2 Bradley and the like, etc. In fact, in some ways it may even be a bit of an improvement. Smoke grenade launchers are a given on an armoured vehicle, for obvious reasons.

The HMG ideally would be mounted inside a small turret allowing the Commander (or Gunner, if a 3-man crew is necessary) to fire and reload the gun inside (if the HMG is gas-operated, and not recoil-operated, modifications to the HMG will be necessary to prevent gas fumes from entering the turret). A hatch in the roof of the hull would be best for reloading the ATGM launcher (somewhat as M-2 Bradley also uses, although a Javelin or Spike-type missile would be much lighter than a TOW!). A minumum of 1,000 rounds of HMG ammo would be necessary (preferably much, much more, along with 2 or 3 spare barrels, etc.), but probably no more than a dozen ATGMs (of Javelin or Spike size, not TOW, HOT, etc. size,) could be carried onboard (including those already loaded in the launcher) or even be necessary (after all the tanks and the heavy-anti-tank weapons are the principle anti-armour weapons, not the IFV). This is also important to remember when considering that the maximum range of fire-and-forget ATGM in the class of Javelin and Spike is 2,500 m. Heavier weapons with greater range are available, but they are not fire-and-forget (with maybe one or two exceptions) and these are the very weapons that are best employed by heavy-anti-tank units.

Two additional considerations for the main armament of the IFV. First, if possible the HMG should be fully stabilized in both axes for accurate fire on the move and at helicopters, and the ATGM ideally should be able to be fired on the move; these are important, especially in offensive operations. Second, the HMG and the ATGM should be able to be removed and mounted on tripods for anti-armour work from dug-in position during defensive operations. The HMG and ATGM are partially wasted in their usage during defensive operations when they remain on the IFV. They are much more effective when firing into the enemy flanks from dug-in positions. The HMGs would efficiently despatch the enemy light armour while the ATGMs would engage the tanks. The idea here is that, unless the enemy acheives a decisive break-through (in which case the HMGs and ATGMs must be quickly re-mounted on the IFVs), the infantry should fix the attacking enemy forces while the armour with their tanks deliver a counter-attack to destroy the attacking enemy force.

This is by no means an exhaustive analysis of the requirements for an IFV. Arguably, however, it can give one some idea of the tactical issues and practical difficulties involved in conceptualizing a proper Infantry Fighting Vehicle.